In the last segment of our commercial pricing guide we will tackle the least talked about and most misunderstood portion of your invoice; the licensing fees. I will go over what they are, why you should be using them, and my preferred method for calculating them no matter who my client is!

To date you've learned about why it is important to price your work, how to invoice your clients for costs associated with your production, how to find out what you are worth, and now today let us talk about your license fee.

What Is A License/Usage Rights

The license is an agreement between you the photographer and the client as to the usage rights that have been granted for a given project. It might help if you think of the license as a lease and the usage rights as the terms of that lease. When you create a commercial image, or any image for that matter, you as the creator are always the copyright holder. When you give your images to a commercial client, you are not selling your images to them, but rather, renting. Sure the client pays you for your time to create the vision and that is what your creative fee covers. However, because each client is so unique and has such varying demands for your images, we can’t possibly rely on your fixed rate creative fee to cover all these variable possibilities. Issuing your clients a license allows you to “rent” your images for their specific needs.

Why Is It Important?

Without a license, the client is completely free to interpret the usage rights however they wish and this can lead to some rather unpleasant situations. One famous example that shows the power of a license is that of the Nike logo. The creator of the Nike swoosh logo was originally paid just $35 for her creation. At the time Nike was in its infancy and the creator had no reason to believe the company would be worth anything, much less, stay in business. Since there was not a license in place the creator of the logo was not entitled to any royalties resulting from the massive growth of the company which resulted in her creation being one of the world’s most recognizable logos. Nike later rewarded the creator with shares of its company; however not all clients will be this giving. To protect yourself and your clients from possible disputes simply draft up a license that both parties can feel good about. The license is your ticket to a safe and prosperous long term business relationship.

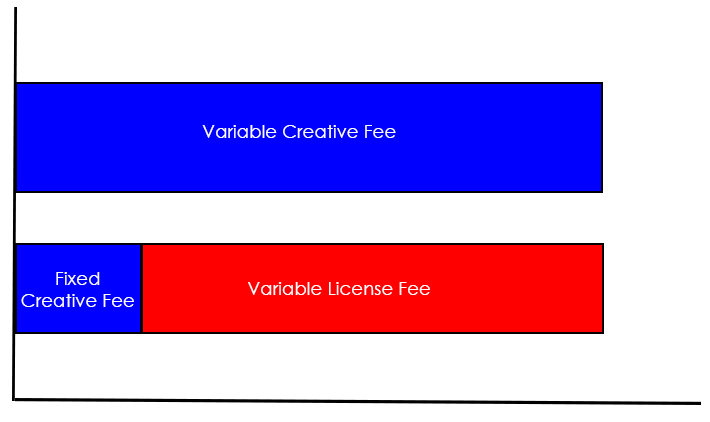

Your license will be a crucial part of your commercial invoice because it allows you to scale your invoices based on the type of projects you receive. It wouldn’t make sense to try and raise your creative fee to scale your invoices because the creative fee, as we discussed in the previous article, is based upon how much your time is worth. It is a fixed fee. Your time should not be worth more for certain clients as opposed to others. If you have a day rate of $2000, then that is the creative fee you will quote to small local retailers as well as to Fortune 500 companies.

As you can imagine though, a Fortune 500 company will have far more use for your images then a local retailer. The local retailer might use your images to generate $100,000 worth of revenue each year, whereas the Fortune 500 company might use it to generate tens of millions in revenue. If both companies needed a picture of a shoe, clearly one of them stands to profit quite a bit more using the exact same image. There has to be a way for us to scale our invoices.

This is where the license comes in. Through the license you will be able to define the terms of usage for each company, and cater the scale of the project to their individual needs. The local company might only need your images for a couple thousand flyers, some local newspapers, and one billboard. The Fortune 500 company on the other hand might need to place your image in a TV spot, hundreds of billboards, international magazines, and on packaging. Once you know where and how the images will be used these will become the terms of your license agreement. You will bill for them separately from your creative fee and production charges, thus being able to charge for the exact exposure the project will receive, as opposed to raising your creative fee from client to client in an attempt to see what your client is currently worth. That is a terrible practice because you are basing your entire estimate on price gouging. If instead you leave the creative fee as a fixed rate, and modify your license fee and usage rights to suit the client, you can come up with an estimate that has some method to it as opposed to being drawn up from thin air.

How To Define Usage Rights

The first thing you need to do is ask your client what the intended use of the images will be. Will these images be strictly for business to business presentations? Will they be used for local flyers? Maybe they will be used in a full page ad for a national magazine? Whatever the case may be, you need to sit down with the client, and ask them rather bluntly the full details of their intended usage. The next question you will have to ask will be, how long do they intend to use these images for? It may seem like an odd question but it is an important one none the less. Most licenses are drafted with a time limit because in reality clients do not need an image for life. It is rather normal for clients to overhaul their products every couple years to re-brand themselves and keep up an appearance of being fresh and up to date.

Some clients will be under the unfortunate impression that once an image is created for them, it is theirs to use for as long as they please. Since the license is really more like a rental agreement, by asking for lifelong usage, the client is in fact asking to be overcharged. It is quite counter-productive to offer your clients a lifelong license when the odds are they will need new pictures after a few years. To keep costs down for your clients, it is best to offer a standard license term, generally between 1-5 years based on the life cycle of your client’s product.

Once you know all the details, you are able to create a legal document known as the usage rights that will clearly state each and every media outlet as well as its related time frame and all other pertinent information relating to the project. I won’t go over how to actually write a license because there is quite a fantastic article for that on the ASMP website. They have a very detailed guide on how to structure your license and how to word it properly.

How To Price Your License

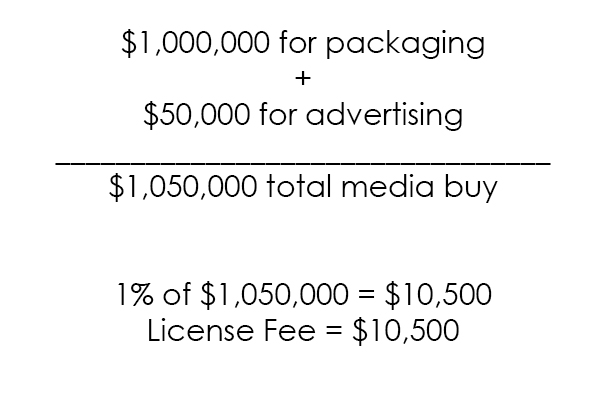

The easiest and simplest way I have found to price a commercial license is to simply find out what the total media buy for your particular project is. The total media buy is another way of saying, how much money is your client spending on the media outlets where your image will appear. Most clients will have a pretty solid understanding of their marketing campaigns for which you are creating the images and will be able to offer you precise figures.

Marketing campaigns come in all shapes and sizes. Small local retailers might only intend to use your image in a local paper for 1 year. This might cost them $3500. A larger international retailer on the other hand might use your image in a multitude of places, and their budget for that might be $350,000.

In order to fairly value our work we employ what is known as a sliding scale. A sliding scale simply means that the more money your client spends on their marketing campaigns, the bigger the discount they receive on their license. The reason for this is quite simple. If we had a flat 20% license rate for all our clients then the client who only spends $3500 on his marketing will owe us $700. That is still fairly reasonable. Yet if we try and charge that same 20% to the client spending $350,000 we need to price our license at a whopping $70,000! That wouldn’t fly in any market.

On the other hand if we charged a 1% license rate, then our client spending $350,000 would only need to pay us a license fee of $3500. That is quite reasonable. However if we keep that 1% for our smaller local client and apply the 1% to his $3500 marketing budget, we are left with a $35 license fee. That hardly seems worth our effort.

As you can clearly see, we need to employ a sliding scale which allows us to charge a higher license rate for smaller clients to offset their smaller marketing budgets, whereas larger clients who have bigger marketing budgets will receive a smaller license rate from us so that we don’t over price our services.

How you structure your sliding scale and the percentages you use are completely up to you. There really is no “industry standard”. There are acceptable ranges and you will learn those over time as you price out projects within your own individual markets. As an example, here is how you might lay out such a sliding scale:

How Would This Work For Our Client?

In Part 2 of this series we introduced our sample client. As you may recall, they needed two images of their useless systems, for which we have currently priced out the production charges and the creative fee. After speaking with the client they told us one of the two images we created would be used strictly for packaging of their product. They believe they will have a new version of the product after 2 years and anticipate creating no more than 100,000 units of the product. Their estimated packaging cost will be $1,000,000, or, $10 per package. The second image we created for them they wish to use to promote their product through a one page ad in a technical publication that has a quarterly release in the USA. They intend to advertise for four quarters and will be spending $50,000 to reach about 1 million people. These will be the only two media outlets so the clients total media buy in this case would be $1,050,000. If we reference our sliding scale from earlier in the article this particular client falls in the 1% licensing fee range. 1% of the clients $1,050,000 total media buy is $10,500 therefore that is our license fee for the project. It is as simple as that!

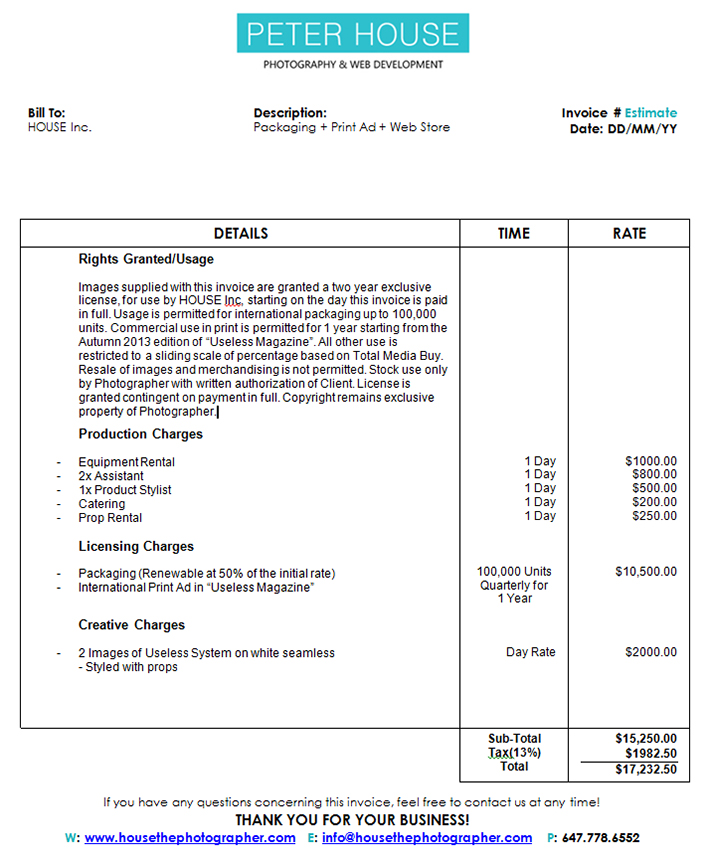

Adding It To The Invoice

Now that we have our license fee calculated we are ready to add it to our invoice. In addition to the license fee I will include a short and concise description of the usage terms right on the invoice. The full terms and conditions will be included with the invoice, but because nobody really likes to dig through all that legal jargon, I personally like to include the condensed overview on the invoice for easy reference. Finally, we get to add our license fee onto the invoice, and once we do that our entire commercial invoice is complete. This is what the completed invoice will look like:

Above And Beyond

As you may have noticed on the invoice, I have included a clause which states that upon renewal of the license, the fee will be applied at 50%. This is an option which you can include because once the terms of usage have been set in the license agreements, most clients don’t intend to go beyond them. Should a situation arise where they need to, you can offer them a price break for that unforeseen future use. An example of this might be if you shoot catalog images for a client. Styles usually change with every season and most images are not considered current beyond 2 years. If a client has unsold articles which he would like to place in a clearance sale, you can negotiate a license renewal, but it might not be fair to charge the full rate for such a use. Thus offering a 50% discount in these situations is a welcome courtesy.

This concludes our series on pricing your commercial projects. I hope you have found the articles useful and thorough. If you have any questions, feel free to include them in the comments section, or you can always email me directly. Till next time, feel free to visit us at Peter House – Commercial Photographer to follow our work.

If you'd like more professional tips on the business side of photography, Fstoppers produced a full course with Monte Isom, Making Real Money-The Business of Commercial Photography that includes lessons from the highest paid photography gigs out there along with free contracts, invoicing times, and other documents. If you purchase it now, you can save a 15% by using "ARTICLE" at checkout. Save even more with the purchase of any other tutorial in our store.

Excellent article and very helpful, thanks

I was just asked to do a project like this and I know I've been doing it "wrong" for years. I love that I found this. I'm wondering how you get clients to share that financial info. Most people I've discussed licensing with think I'm ripping them off and that the images are theirs to do whatever they like with. If I asked for financial info they'd probably laugh me out the door.

Simple question, is there a sale tax on the licensing?

It seems to be the case when I see the invoice sample.

Absolutely awesome...and I know I'm coming late to the party... ;)

Where is Part 1? Thank you for this!

Great article Peter, but I want to echo some of the questions that many others have brought up but have yet to be addressed.

I've gotten a ton of push back from clients when I ask a client about their total media buy, since it is technically private company information that they don't want to share with an outside entity, like a hired photographer for instance. So if I'm unable to get an answer out of them about their total media buy, how do I price my licensing fees appropriately?

Additionally, how do I verify the actual numbers they're giving me (if they end up actually being that transparent)? What's to stop them from just giving me completely inaccurate numbers?

On another note, if a company or small business hasn't yet determined their media buy, or there isn't even a media buy established because the photos are for internal use or employee use (like staff headshots), how do you price that out?

I like the idea of a sliding scale rate because it seems fair to the client/project budget, but this doesn't seem like something that any company would be transparent about or be willing to share with an outside party.

Any advice and guidance on these issues would be appreciated since these questions have been brought up a few times! Thank you again for the great article!