Ever wondered what your images sound like? Well, you can find out with a strange process known as sonification.

The idea of hearing what an image sounds like is a ridiculous concept to comprehend. Photography and audio production are vastly different worlds, with completely different equipment and processes involved. So, how on earth could you hear an image? And what would your images sound like? With sonification, a post-production process, you are able to take a still image and convert it into sound. Essentially, it translates the visual data into audible data through a stream of clever conversion. It sounds bizarre, but sonification has a variety of purposes in many different fields.

What Is Sonification?

To understand this unique cross-media technique, I spoke with Liam Taylor, an audio wizard from the UK. Liam frequently experiments with audio/visual crossovers, using technology to further artistic possibilities. He often posts these creative explorations to his YouTube channel. Liam said that in order to begin sonifying your images, you first need the right software. He recommended Photosounder, which costs $79 for the full version, but a free demo is also available. It works by taking the visual data from your image and generates audio using only that data. The sound is essentially a variation of white noise and is affected by various elements from your image, such as exposure, position, and lines.

Image sonification within Photosounder

Liam mentioned that Photosounder plays images from left to right, just like how we read text. In other words, the X-axis of your image represents time, meaning the left side will be played first. It then scans horizontally, playing back the raw data live. The Y-axis, however, represents frequency (pitch). This means any detail towards the top of your image will be played as a high, chipmunk-like pitch. In turn, anything at the bottom of your image will be deep and bassy. Lastly, the volume of the audio is dependent on the brightness levels in your image. Liam stated that the brighter the area, the louder the sound will be, and vice versa. So, let’s say we have an image of a bright, distant moon, center-framed, against a black night sky. If we were to convert this using Photosounder, what we would hear would be silence, followed by a series of loud sounds, then silence again. The pitch of the sounds would be determined by the size and vertical position of the moon, while the complexity of the sounds would be affected by the moon's detail.

There are various attributes you can change within the software; therefore, more creative controls are in your hands. I asked Liam about the length of the audio clip and how that was decided. He said you have complete control over the duration of the outputted audio. Have it play for as little as one second, or slow it down to three days! Additionally, you can change and limit the frequency range that the software uses. You might do this if your image is sounding too messy and you want to limit how much sound is produced.

It’s not just limited to creative uses, though. Sonification can be used for research purposes, employed to search through patterns of complex data. Liam mentioned that the human ear is often better than the eye at detecting patterns. Researchers will convert data into audio in order to spot recurrences within complicated data strings.

What Does an Image Sound Like?

After learning more about sonification with Liam, I was extremely curious to hear these sounds and compare different images. Liam showed me some previous examples he had made using experimental images. From first impressions, it was awful. The first image, which looked like hundreds of stars in the night sky, sounded all over the place. It was basically a chaotic, digital cluster of sound that was not too kind on my ears. I was certainly skeptical, but then he showed me a picture of fire. This bright, orange flame against a black background when converted, played back a roaring, whooshing sound. A sound that was uncanny with real fire.

This piqued my interest, so I was very keen to experiment with this process. Up until this point, I had only been shown very simple examples, but I wanted to hear what photos from professional photographers sounded like. I reached out to my fellow staff members at Fstoppers to borrow their images for this experiment. I handed these off to the audio wizard, and he shared the results in his video below.

Liam imported the images to see what kind of wild sounds they would produce. I was surprised when I heard the bizarre, yet satisfying audio playback. Each image sounded vastly different from one another, differing in complexity and overall mood. However, they shared one thing in common: they all had a strange, alien-like quality to them. I could imagine them being used in the sound design for a sci-fi movie set in the 80s! Liam then demonstrated how you can take these sounds and sample them for MIDI instruments. This effectively gives you a unique sounding instrument that can be played via a MIDI device, like a keyboard.

Creative Applications

Sonification is a very interesting technology concept that I was otherwise unfamiliar with until recently. Having spoken with Liam Taylor, I can only imagine the endless creative possibilities. In fact, it is not uncommon for professionals to use sonification as a way of planting Easter eggs into their work. Mick Gordon, the composer of the computer game Doom, hid symbolic signs within his music. He manipulated the sound of these to exist within the higher end of the frequency range, allowing them to neatly sit in the mix. This method meant Mick could incorporate visual Easter eggs within the score without harming the overall balance.

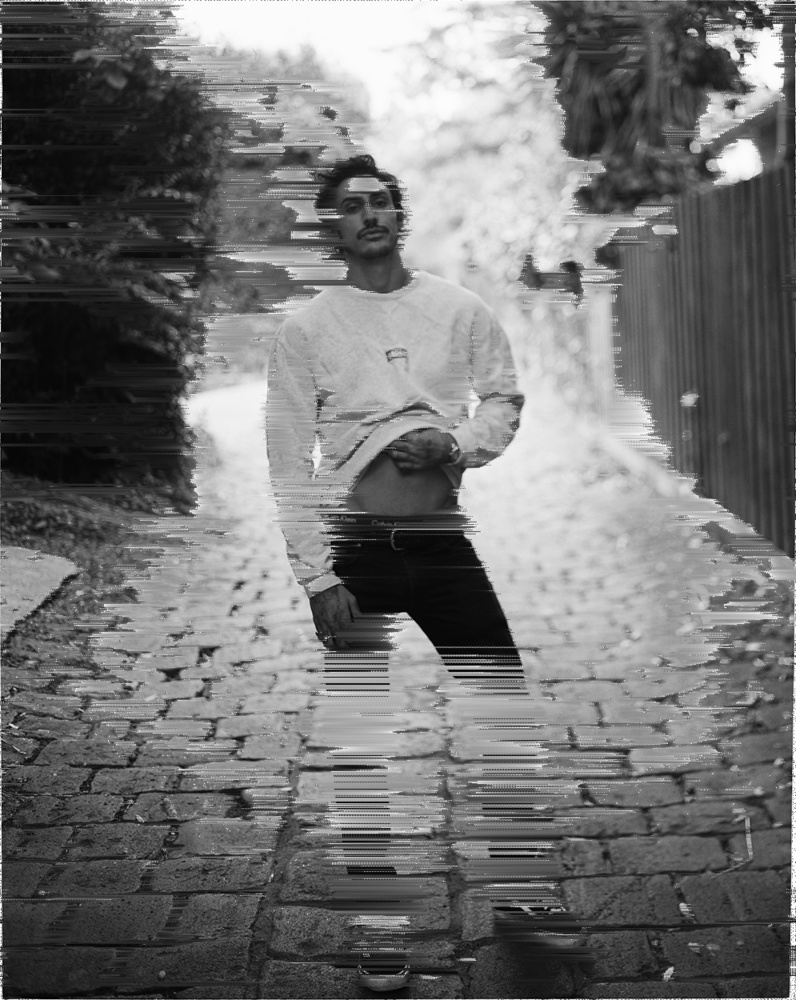

Turns out this process isn’t limited to changing images into audio. It can also do the reverse, converting sounds into a visual representation using similar methods. This is exactly what Ali Choudhry, photographer and Fstoppers writer, did in his experimentation. Ali scanned a 4x5 film image and converted that into an audio file. This piece of audio was then manipulated by Ali, before being converted back into an image again. This cross-media round-trip created some interesting artifacts within the image. These artifacts would differ depending on what Ali did to the file when it was in audio form. You can see the results below.

Images by Ali Choudhry | www.alichoudhry.com

There are so many creative possibilities with sonification, especially with the flexibility you have in Photosounder. However, it’s worth noting the somewhat random feeling that comes with this peculiar process. The sounds it produces can sometimes be very chaotic with certain images, while other images can be very soothing. Truth is, you will never really know how it will sound until you convert it. It reminds me of the fun of shooting a film; even if you’ve taken time to compose and properly expose a shot, you won’t fully know what it will look like until you see the results later on. With some dedication and patience, I think sonification can be a very beautiful way to create artwork that’s rich in creativity and uniqueness.

How would you incorporate sonification into your work? Let us know in the comments!

Images used with permission.

MAX MSP programming software can be used to translate video/images into sound for those that are interested.

https://cycling74.com/products/max

Ace. 😊

Thank you! :)

Audacity is open source and is what I used.

https://www.audacityteam.org/