There are a thousand skills — technical, artistic, and observational — that need to be mastered to make great images. But to really get better we have to, first, learn to do this.

Step Outside Your Own Head

My latest attempt to embarrass myself is by trying to learn to play the drums. One of the suggestions you hear over and over again when learning an instrument is to record yourself and play it back. Your brain listens and hears in a different way when its responsible for making music than when it’s just jamming to something coming out of a pair of headphones.

The context is different. The expectation is different.

Muddy playing, a missed note, getting a little behind the beat, my brain will forgive me these things in the heat of the moment. But hear them played back through a set of headphones and they're like someone sticking something pointy in your ear, repeatedly, and not even bothering to do it with decent rhythm. Your brain expects the Beatles or Zeppelin. It expects perfection, emotion, grace. The change in context can be jarring. And illuminating.

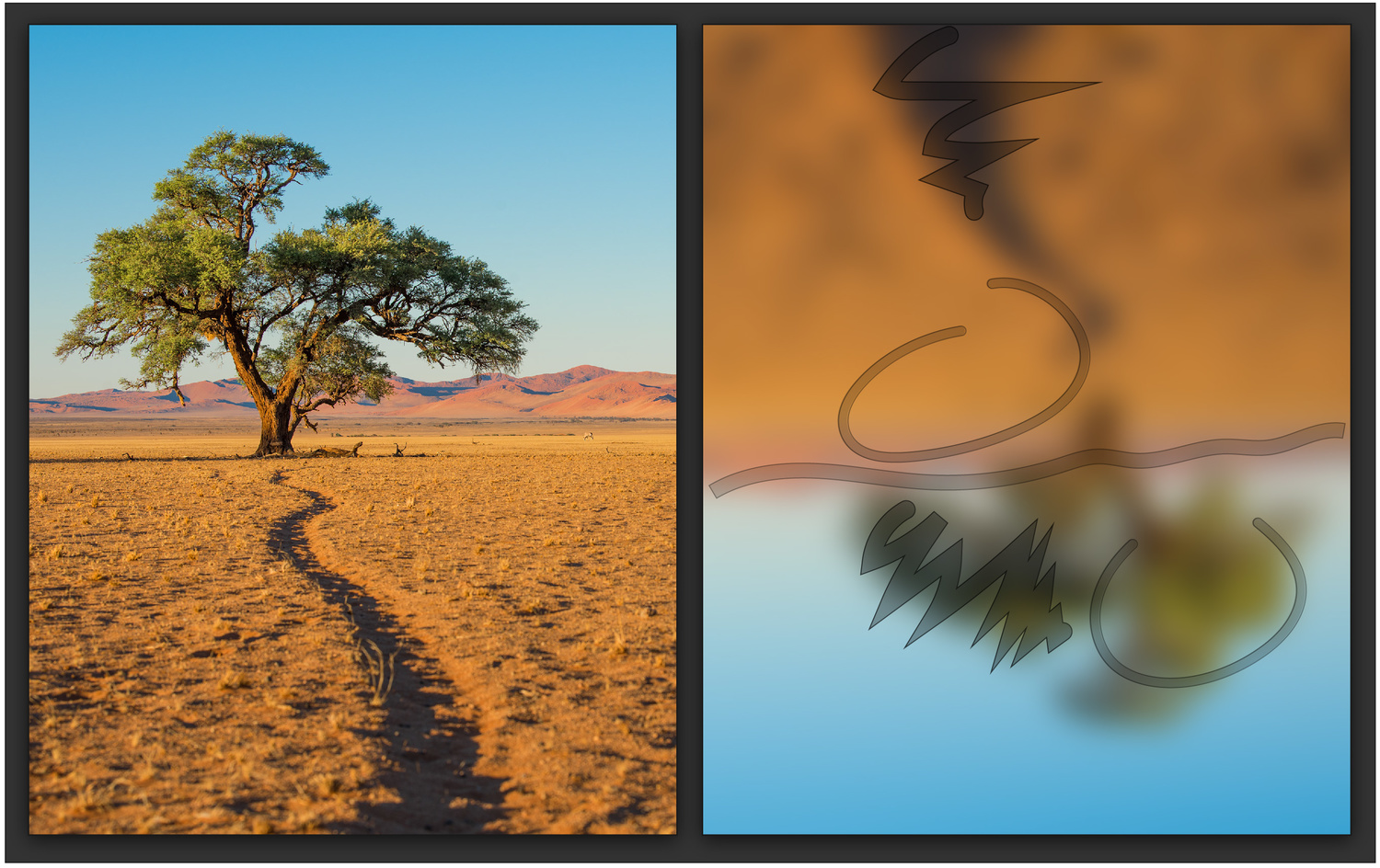

By flipping an image upside down and squinting a bit, you can often see the underlying compositional elements much more clearly.

My first art teacher had a similar insight. We’d walk whatever painting I was working on out to her couch where we’d set it against the cushion. We’d step back and peer at it for a minute from across her living room. She’d ask me what I thought. Then she’d quietly walk up and turn the painting upside down and ask me to give it a good squint. A whole new abstract image would emerge. The trees and sky and paths would disappear and be replaced by an abstract collection of edges, colors, and forms. The compositional elements of the work would come to the fore.

These same ideas can be valuable in photography, as well. Obviously, we too can flip our images upside down and give them a squint. The exercise can be enlightening. But there are other ways to experience our work from a fresh perspective, too.

Judge a Photography Competition for Yourself

I don’t literally mean create your own photography competition. Instead, enter your work in a contest and leave it sit for a while. Give your brain a chance to move on to other things. Then, eventually, wander back around and take a look at the competition gallery. Scroll slowly through the other submissions, the works that hundreds or thousands of other photographers have submitted in the same categories to the same contest. Pretend you’re a judge, that you have to decide which photographs still need some work, which should make it to the final round, and which should get awards. It’s likely that ninety percent or more of the photos won’t be real contenders. Why not? What set of characteristics do they have in common? What are they lacking?

Fynbos, Western Cape, South Africa. How do you think this image might stack up against others in a contest? What’s it got going for it? What’s it missing?

What traits do the better images share? Trying to figure this out can be an incredibly valuable exercise in its own right. If you’re lucky, too, as you’re going through the galleries, page-by-page, you’ll run across your own work embedded in a sea of other photographers’ images. With your judge’s hat firmly fitted, you’ll likely see your own images in a different light, without the biases and preconceptions you normally view them through. Which group does your image belong in? Does it need a bit more work? Is it a finalist? Should it be an award winner? Did it stand out to you immediately, not because it was your image, but because it was better or fundamentally different than the other entries, or was it one among a sea of similar contenders?

Don’t think about how you came to make it, where you were, or what the story behind it was. All the actual competition judges will see is the image. If it doesn’t tell the whole story, elicit just the right upwelling of emotion, or convey the fully unhindered meaning you intended it to, it will likely fall flat.

My Own Shortcomings

I recently submitted a few images to a photography competition. The contest was meant to highlight Africa, its lands, peoples, and wildlife. A few weeks after the submission process I went through the exercise above. Indeed, most of the submissions — at least to my eye — still need a bit of work (my own submissions most definitely included.) There’s often something missing: the moment, the drama, the magic light, the height of the action, the artistic vision. Most of the images fall a bit short.

But there are standouts; exceptional images from which there are lessons to be learned. The caption to one of my favorites — a great shot of a bull elephant head-on against a faint, dusty hillside — includes the words “and we waited”. It’s confirmation of Nils Heininger’s emphasis on the role of hard work in making a great photograph. To make the image of the fynbos above I, too, went back three separate evenings to that same spot in the trail with my wife “and we waited”. Yet, to me, something is still missing in the image, the full force of drama or an element that surprises.

Thirty minutes later, as we made our way down the path to our cabin, we spotted caracal loping through the trees in the dimming light. If I could only have gotten him to come pose on the trail for me the next evening at sunset, then I’d have had a shot!

A local boy after looking through a pair of binoculars for the first time in Uganda’s Lugogo Swamp.

So, too, with this smiling boy in Uganda. It’s a genuine moment of relaxed joy shot at sunrise while we were tracking an endangered Shoebill through the Lugogo swamp. We let him (the boy, not the Shoebill) look through a pair of binoculars for the first time. He was amazed. He laughed in wonder. The image above captures something of that simple joy, but it doesn’t tell the full story. And that’s its shortcoming.

The other benefit of this exercise is getting to see of ton of other photographers’ work. There were submissions that were beautiful, creative, captivating, and inspiring. They not only made me want to be a better photographer, but with a little reading between the lines, gave me some clues about how to do so.

So, give it a whirl. You’ve got nothing to lose. Except maybe a competition.

Thanks for highlighting the technique of flipping and squinting as another way of assessing a photo's composition. I learned that technique in high school art class many years ago, but it had long been forgotten. I plan on trying that out again on my photos to see how I can reassess my compositions as a critue of my own work. Cheers!