We catch up with photographer Simon Murphy who currently has a major exhibition of his work, having cast his lens on the Govanhill area of Glasgow over the last 20 years. Learn key insights into his methods, how he connected with members of this diverse community, and what advice he would pass on to photographers seeking to embark on long-form documentary projects.

Over the past twenty years, Simon Murphy, an award-winning photographer and lecturer from Glasgow, has photographed members of the community in a small yet diverse pocket of Glasgow. Less than one square mile in size, the area is known for its thriving immigrant communities, and is home to a myriad of independent shops, cafes, and restaurants, adding to the dynamic character of the neighbourhood with its unique blend of heritage and modernity.

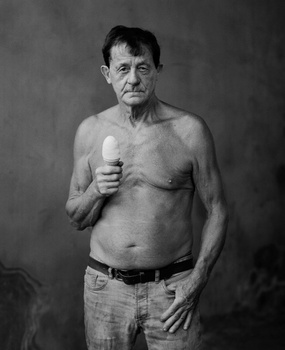

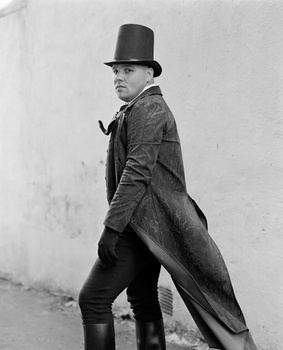

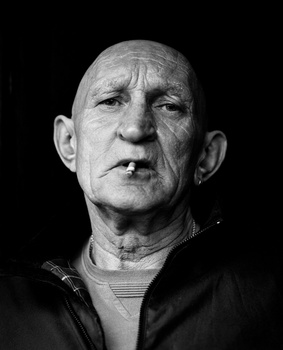

Govanhill, once referred to as The Most Demonised Neighbourhood in Scotland serves as the backdrop for some of the most striking and original portraits you are likely to have seen for quite some time. This exhibition of works is a wonderfully positive contrast to the kind of negative stereotypes that often befall working-class neighbourhoods like Govanhill and the people who live there.

As I enter Streetlevel Photoworks; a gallery which I have visited numerous times, the space has been transformed to host the current exhibition. Govanhill is a collection of diverse portraits, all striking for their individuality, but equally tied together by their difference and distinction. Key walls have been adorned with black, as a backdrop that allows these captivating medium format black and white prints to leap out at the viewer. If you are lucky enough to be in travelling distance of Glasgow in Scotland, this exhibition is well worth a visit. If you are further afield, the exhibition can now be viewed virtually.

Exclusive Fstoppers Interview With Photographer Simon Murphy

I asked Simon 10 questions about his wider work as well as the process of shooting the exhibited images. Get comfortable and read on for an interesting insight into this excellent example of long-form documentary storytelling.

Can you tell our readers a little about your wider photographic practice and your background?

I used to be a postman, and sometimes, I would deliver postcards. The photographs of far-flung places made me wonder what it would be like to travel. One day, I delivered a postcard with a picture of the Beatles on it. It was a lightbulb moment when I realised that it wasn’t only the Beatles who were present but they shared that moment with the photographer. You never see the photographer but they are present in every iconic moment in history, experiencing it and sometimes creating and shaping it. That captured moment inspired me to leave my job in the post and pick up a camera. When I began my photographic career I was drawn to the images of Avedon and Bailey, photographs of musicians, actors, and artists. I love shooting similar subject matter but my heart is with the everyday man on the street. My photographic career properly started with a job for the Herald, the National newspaper of Scotland. That job took me around the world. The experiences and stories I heard shaped me.

What was the initial spark which drew you to Govanhill, and prompted the beginnings of this project?

The “Govanhill” project began in 2000 when I was a student and living there. Any college assignments were undertaken there because it was convenient. Around 2010, I changed my job and became a lecturer in Photography. I still shot assignments but I felt I needed a personal project to fulfill my creative needs. I needed a project nearby that I could fit into my half day discretionary time. I realized that all the things I loved about my days travelling were actually right there in my doorstep. Govanhill is a small area in the southside of Glasgow. Less than a mile squared but home to around 80 languages. Around 2016, I threw myself into documenting the people of the area.

Can you elaborate on your methodology during the early stages of the "Govanhill" project and how it evolved over the 20-year duration? Were there specific challenges or discoveries that prompted adjustments in your approach?

When I began the project or rather picked up the project again, I wondered about approach. Would it be captured moments of street photography? Stylised and setup portraits? I tried a few approaches but settled on very informal portraits of chance encounters… people as they are in that moment. The approach goes back to my days as a postman, I wander. The repetition of the postman’s walk got me into a mental state where I was free to dream. That’s when the ideas came and I tuned into another wavelength. I do the same thing with the project, I wander. I walk the same streets repetitively and get myself into a state where I start noticing details. I tune out to tune in.

Most of my images involve opening myself up to people, strangers. It’s a collaborative dance sometimes lasting only a few minutes but one where lasting relationships might be formed. When I travelled and covered human interest stories in far flung countries like Bangladesh and the DR Congo, there was an obligation, responsibility and care taken with the imagery and stories created. I try and bring the ethics of what I learned into my street portraiture.

Your chosen medium for this project was black and white film shot with a medium format camera. Does this specific choice contribute to the storytelling and the overall aesthetic of the project?

I don’t believe film is better than digital, but the approach and process is different. I carry a bulky medium format camera on a tripod that cannot be hidden so I have to be very open about who I am and what I am doing. No sneaky approach. I have to shoot less frames from a cost point of view so perhaps I take a little more care at the shooting stage but this also results in me being less experimental. Being less experimental might make the shots look a little repetitive but also gives them a strong and consistent style. There are positives and negatives, but the negatives literally become positives. Shooting film means that I can’t show the sitter the image right away which gives me the luxury of only showing them the best shot. You can easily make a digital shot look like film but you tend not to get the same nostalgic and intrigued reactions from people with a modern digital camera. The camera itself can open the door.

How did you establish a connection with the people featured in your photographs to capture such intimate and authentic portraits?

When I wander, I am also working on my outlook. It’s a positive project, a celebration of people from all walks of life. When I see someone and there is an internal reaction I take note. What was it I noticed? Why did the person trigger this response in me? I ask myself those questions within milliseconds and also ask myself: what do I love about that individual? I realise that might sound over dramatic but I have seconds to pluck up the courage to approach. When I introduce myself and the person asks me why I want to photograph them? I honestly relate the answers to the internal questions I have just pondered. People read you very quickly so an honest, enthusiastic approach is essential for success.

You have previously described these images as a portrait of a place. Can you explain what you mean by that?

I generally don’t give the back stories of the people I photograph as I am mindful that carelessly chosen words can label a person, sometimes negatively. This is a huge responsibility, especially as the work spreads further. The project isn’t really about individuals in any case, it’s about a place. Govanhill is an intriguing place, a place I love dearly because of its diversity. Collectively the images help form a portrait of the place. In this sense, Govanhill is the character, a multi-faceted, quirky, intriguing, conflicted, contradictory, exciting, cultured, brave and strong individual.

Your first major book 'Govanhill' has been described as a one-of-a-kind masterpiece. How did the process of curating images for a book differ from preparing for a gallery exhibition?

I relinquished control. I know that sounds risky but I believe in people and I believe in collaboration. When Primal Scream handed over their songs to Andrew Weatherall, something new and exciting, groundbreaking even, was created: Screamadelica. For the exhibition, I created the narrative and curated but the book was in the hands of the publisher. There were certain images that I insisted be included and the raw material was completely mine, but I trusted them to treat my images with care and also bring something new to the table.

What role do you hope your photographs play in sparking conversations about Govanhill, both within the community and in the broader social and cultural context?

I’m a believer that small actions can create big moments. Ripples can become waves. My initial responsibility is to the individual that I make the photograph of. I want to craft the image well and would like them to be proud of it. If something is done well, others will take notice and the wave begins to swell. If something is done well, people then take the craftsmanship for granted because it does it’s job, then they think deeper about the subject. My hope is that the viewer will now look into the eyes of someone, perhaps from a very different background to themselves, and think about that persons life. Maybe they will conclude that as humans, we are not so different. Maybe they will be more open to conversing with someone new themselves and maybe bridges will be built and doors opened. The purpose of art is not to tell people what to think, it’s simply to get them to think. These thoughts can be a catalyst. Govanhill is a microcosm for people all over the world and these portraits I hope will be relatable to all sorts of people no matter where they live or the circumstances they face.

Has the Govanhill project shaped your broader approach as a photographer, and what lessons or insights have you learned?

I don’t think we are ever the “finished article.” The project combined with my own growth as a person has shaped me and my approach. It’s reinforced my belief in the power of art and photography but also is a constant reminder that if you open yourself to others and push yourself out of your comfort zone, amazing things can happen. The project has enriched my life and taught me so much.

Having been on this journey for the past 20 years, what would be one piece of advice that you would give to photographers seeking to begin a long-form documentary project of their own?

Ideas come out of the process. The process begins by putting your shoes on and getting to work. If you repetitively and enthusiastically embrace the chance to go out with the camera then the project will come to you. Allow yourself time to meditate on your motives but don’t think too much in case you allow yourself to talk yourself out of making pictures. The camera can change your life so don’t hide it. Embrace who you are, a photographer. Accept that you are constantly learning. Be enthusiastic and humble. Be excellent to one another.

Many thanks to Simon for sharing his insight into the creation of these captivating images, and for sharing his expertise. The Govanhill exhibition runs until January 27, 2024 in Streetlevel Photoworks and is certainly worth taking the time to visit.

All images used with permission of Simon Murphy.

A fantastic collection of images and a story to match.. Thanks Kim

Right? Glad you enjoyed it. Have a look at the virtual exhibition for the full experience.