How many megapixels do you need to print a billboard? Much less than you probably think.

Every year, our cameras are packed with more and more resolution. When asked why we need this many megapixels, most photographers use the same excuse: "well, I need the extra resolution in case a client wants to print one of my shots on a billboard." Is this true? Haven't billboards been around for hundreds of years? Long before 50-megapixel cameras?

PPI Versus DPI

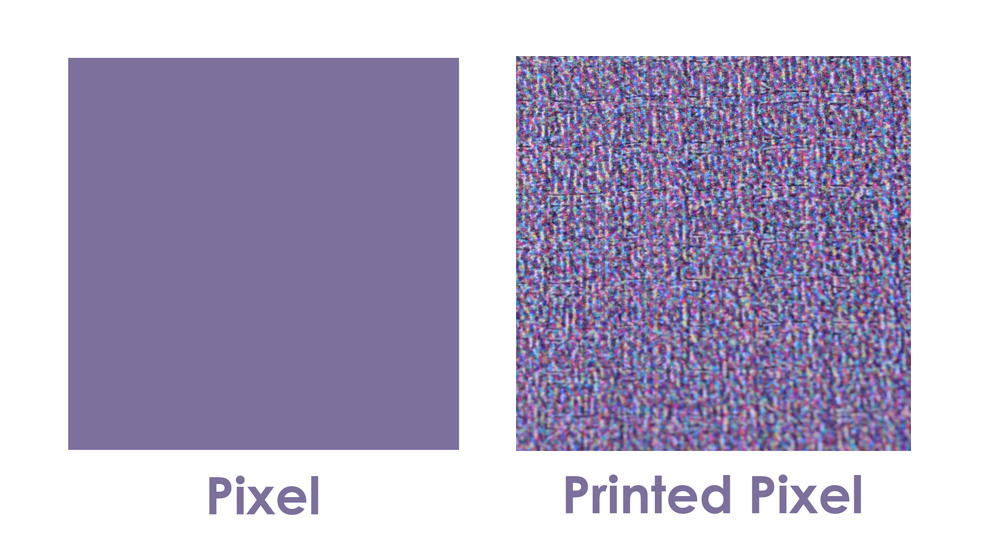

Before we get into the exact resolution needed to print a billboard, let's talk about ppi vs dpi. Most of us use these terms interchangeably, but they aren't technically the same.

What is PPI?

PPI is pixels per inch, and as photographers, this is what we are most accustomed to. A pixel is simply the smallest unit of a digital image that can be captured by a digital camera or that can be seen on a digital display. A "megapixel" is one million pixels and by multiplying the vertical and horizontal pixels of an image, we can determine how many pixels we are dealing with altogether. The Nikon D850 will produce a digital image that is 8280 pixels wide by 5520 pixels tall. If you multiply those two numbers, you will get 45.7 million pixels or 45.7 MP.

The important thing to remember is that an abstract pixel itself does not have a physical size; it's simply the smallest unit of a digital image.

Pixels per inch becomes useful when we take a digital file and bring it into the real, physical world. Let's use a computer monitor as an example. Our computer monitors have a fixed resolution. A small 1080p monitor will have more pixels per inch than a larger 1080p monitor even though they have the exact same amount of pixels (1920x1080). A 4K monitor will have two times the pixels per inch of a similarly sized 1080p monitor. This means that the same image viewed on different monitors will appear to be different sizes and will have a different ppi based on the pixel density of that specific monitor. Printers are slightly more complicated because they can't produce individual pixels, instead, they must mix tiny drops of ink to reproduce these pixels.

What Is DPI?

DPI is dots per inch, and although most photographers and designers use DPI to describe pixel density, it's technically supposed to represent the resolution of a printer. Many printers only have four colors: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, but miraculously, they are able to produce the millions of colors in our photographs. To do this, the printer squirts out billions of microscopic drops of ink. Together, these drops (or "dots") are able to recreate the pixels that make up an entire image. Have you ever noticed that your photo printer has a draft, normal, and high-quality print setting? In most cases, these settings are changing the resolution of your printer. But let's assume that for all of your prints, your printer will be set to the highest quality. This means that regardless of the image that you are printing, the DPI or dots per inch will remain constant whether you are printing a high or low-resolution image.

Most photo printers these days are able to print at over 2,000 DPI which is far more resolution than the "average" photograph that is printed at 300 DPI and in most cases, more expensive printers can print with even more resolution. Some printers though, like billboard printers, print with much less resolution. On the billboard in the video above, the dots were so big we could actually see them with the naked eye.

Viewing Distance

As you can see by the chart above, the human eye is only able to resolve a certain amount of resolution based on viewing distance, and there is an equation we can use to figure this out:

If we were to use this equation to figure out the maximum resolution the eye could see at one foot (12 inches), we would get 573 PPI. Although some photos are printed at 600 PPI, you have to ask yourself: how often are people standing 12 inches from a photograph? As we double the distance from the print, the human eye is able to resolve half the detail. This means that at two feet, you will only need 300 PPI of resolution and at 10 feet, 60 PPI. Some fine art prints can be enjoyed at a distance and up close, and so, ultra-high-resolution prints may be called for. Billboards, on the other hand, are never enjoyed up close, and viewing distance plays a huge roll in deciding print resolution.

What Is the Viewing Distance of a Billboard?

The data I have found online suggests that the average billboard is viewed from 500 to 2,500 feet away. As we can see by the chart above, once we get beyond 650 feet away, the human eye can only resolve one pixel per inch. Going all the way out to 2,500 feet, a billboard would only need .229 ppi. This means each pixel would be about 16 square inches.

How Many Megapixels Do I Need to Print a Billboard?

In the video above, we are standing approximately 150 feet away from the print. From this distance, we were significantly closer than you would be to the average billboard while driving down the highway, but even from this distance, we would only need four pixels per inch to produce a sharp looking print. The billboard itself is 14 feet x 48 feet in size, which comes out to 96,768 square inches, and we want to multiply that by 4x4 pixels (16), and we come up 1,548,288 pixels or 1.5 MP. At a viewing distance of 2,500 feet and approximately 16 square inches per pixel, that's only 6,048 pixels or 0.006 MP. Even at a closer viewing distance of 650 feet, that's 0.09 MP. The Nikon D850 has about 472 times that resolution.

But this makes sense, doesn't it? Billboards have been around long before these fancy DSLRs. Did billboards use to look blurry, and now, with the creation of the Nikon D850, become ultra clear? Of course not. The truth is that billboards are probably the lowest resolution images we come across on a daily basis.

So, Megapixels Are Worthless?

Not necessarily. If you were only shooting images for billboards that were going to be viewed at over 100 feet away, you probably wouldn't need a high-resolution camera, but some ads are printed large and can still be viewed at close distances. I always liked viewing the wall-sized ads in the subways and bus stops of NYC. Sadly, even these ads never seem to be printed at a very high resolution. But maybe one day, a company will come along and start printing ultra-high-resolution subway ads, and if you have an expensive new camera, you'll be ready.

So what is all of the extra resolution good for? Are you printing gigantic wall art that can be viewed from a distance and up close without losing perceived resolution? You're not? Well, then you probably don't need a 50-megapixel camera. But hey, it's nice knowing that if you ever wanted to make a print that large, you could.

If you're passionate about taking your photography to the next level but aren't sure where to dive in, check out the Well-Rounded Photographer tutorial where you can learn eight different genres of photography in one place. If you purchase it now, or any of our other tutorials, you can save a 15% by using "ARTICLE" at checkout.

At 5 feet, the human eye can discern 120 ppi. In a 30x20 print, that's 3,600 pixels by 2,400 pixels, or about 8.64 MP, as you calculated. All other factors constant, no, the human eye would not be able to distinguish a higher-resolution print at that distance and size.

Wondering how, if at all, this applies to images shot on film and then scanned? Does the scanner apply PPI to your image based on scanner resolution? Does the size of your negative correlate at all to PPI/DPI? In the darkroom the size of your negative usually dictates the size of your print. I feel like scanning might negate this as you're selecting scanning resolution and then can select DPI later? Surprisingly little information I've been able to find for this type of workflow online.

I’m pretty sure that film scanners today have way more resolution than a 35mm negative. So the film itself would be the weak link.

I didn't have time to watch the video but I still have an opinion :D

The last time I did a project for a billboard, the billboard company said that the optimal resolution for all their project is 6 megapixels but that was also overkill for billboards but they requested 6 megapixels so that when they printed other smaller items (like a proof), there was enough resolution for it to still print good. Bottom line is that a billboard is just too far for you to notice the lower resolutions.

The other ridiculous argument I always hear is “well, I have the ability to CROP more and still have plenty of resolution for my final image.

Seriously? Cropping is to be used to remove a distraction, maybe some empty space in the corners after straightening a horizon or merging a pano. However it is not supposed to be a way for a lazy photographer to just fire away on the scene and then come home to digitally “compose” the image in post production.

A good photographer shoots a good composition in camera and then finishes it in post. It is not a crutch to be used as an excuse for poor photpgraphy.

ENOUGH with the MegaPixels! I would far rather see manufacturers working on sensors with better dynamic range. HDR was a technique necessary to compensate for difficult, high contrast lighting conditions in the early years of digital photography, however there is little excuse for still needing to merge multiple images with the state of technology today. They just need to allocate resources to the right things. Also customers need to let them know we don’t need more MPs - we need better dynamic range!

The biggest problem nowadays is that we have photo sensors that have to act like moviecam sensors just to please poor wanabee Spielberg !

For the last 7 years, where did SONY poured its money and R&D in the photo sensor technology ? only getting faster readout and OSPD AF in order to comply to their lousy idea a moviecam is THE one tool to make movies AND photos.

I am sorry, but I do not find any innovation in the SONY sensors : BSI just give us higher readout that please EVF fanatics and 20fps photo camera... At least, we get marginal improvment in the noise control, but take a D800/A7R sensor and compare them to a A7RIII and we are far from looking at serious improvment, only better algorythm and ciruitry. Where is the better accutance ? Better DR ?

In the meantime, they, and the whole fanbase begging for the death of dSLR, totally lost the advantages of the dSLR : the sensor does not have to be always online and at a minimum refresh rate of 60fps in order to give the user a vidual feedback (viva la EVF, what a mistake).

A photo sensor should not have towork at 60fps, it should only be fast enough to sustain a 5-10 fps and use the 'spare time' to be able to better capture photons, get higher accutance, better color precision.

But all the innovation a photographer should ask for a new photo camera is dismissed by whiners asking for speedy EVF and movie features set that should be only packed in a movie/cine cam.

Nice post Lee. I was curious about the "0.000291" number used in the calculation. Just wondering what that refers to? (nevermind. geek-side took over... Apparently it's a calculation known as the 'visual acuity angle' and represents how much resolution a human can see).

I’ve wondered the exact same thing. Alex Cooke also explained to me that the equation could be simplified by cutting the number in half but it’s written like this everywhere.

Yeah, it's just a constant that scales the equation to match the performance of the human eye.

This is fantastic information. I'm glad you posted it in an article too, (I read Fstoppers mostly at work and can't watch videos) was a great source to look back at. I have two cameras, a 20MP and a 24MP, I can't imagine ever needing more.

The only thing that would have added anything to this would have been Lee actually having a mike in his hand and dropping it at the end.

I've been having this argument with people and their cameras for YEARS. Dam fine way to explain it to the masses and place a fork in this conversation once and for all.

Great article, I discovered this a while ago when a client took one of my Canon 5D MK II images and made a billboard from the image and it was quite clear/easy on the eye.

What about when making prints over 20x24 up to 40x60, wouldn't the 50 MP camera be the better choice say for prints hung in a gallery?

As someone who's made billboards, it's all about the printer and their special sauce. While most billboard are good at 12-50dpi. For wall wraps and building billboards need a ton of dpi

Great explainer, Lee. PPI vs. DPI and grand format printing requirements are very misunderstood. This is one to bookmark--because you know you're going to have to explain it all over again next week ;)