Should you think more about having a coherent and distinctive style to your photography? If you want to raise your game, then finding your own look is imperative. There's one surefire way of developing that. However, some big obstacles will try to trip you up along the way.

What Is style?

In photography, style is the distinctive appearance of a group of images. As in other arts, the great photographers have their own characteristic styles, although these may change over time. Style results from a mix of variables that come together, making a coherent look across a body of work.

Genre and Style Are Not Synonymous

Do you pigeonhole yourself into a particular genre of photography? Perhaps you consider yourself a wildlife or landscape photographer. Maybe studio portraiture is strictly your thing. But, then again, you could roam the streets with your camera looking for people interacting with the urban environment. Alternatively, you might seek out danger and put your life at risk as an extreme sports or war photographer.

If you do, then bravo bravissimo. You have joined the ranks of some of the best-known photographers that have ever lived. Ansel Adams shot black and white landscapes, Cartier-Bresson famously photographed people on the street, and Sir Donald "Don" McCullin is often referred to as a war photographer. But these are genres, not styles.

All those photographers also embraced other areas of photography too. For example, his excellent book “McCullin in Africa” documented the sometimes life of pastoral tribes in Ethiopia, near the unsettled border with Sudan. Then, a more recent collection of his is an exquisite collection of black and white landscapes; the quiet peace of the natural world, a stark contrast to the horrors of war and deprivation his lens has witnessed. Nevertheless, despite the different genres, there is an overlap in his photographic style, similarities that help identify the photographs as his.

Style can be something we cannot easily identify or describe, and so it is frequently ignored in photographic discussions. That is because it is the result of a sometimes complex combination of creative elements that give a particular look.

How to Find Our Styles

There is a multitude of things you can do to develop your own unique style of photography. First and foremost is your photographic eye. That means being able to identify a series of subjects that fit together and composing the shots to show those subjects in a way that helps convey your message.

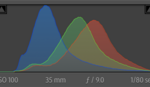

That continuity is reliant on a number of factors: positioning of the subject; focal length; aperture; proximity, showing or stopping movement; lighting brightness, angle, and color; camera positioning; frame aspect ratio; genre. Of course, you don’t need to keep all these factors the same for all photographs. Just choosing a few for a series of photos will add coherence across all the shots.

Where Have all the Styles Gone?

Those 12 factors alone have 479,001,600 possible combinations, and that’s not including other variables such as lens filters, weather conditions, plus image processing, and editing.

Yet, despite this huge variety of possibilities, we constantly see similar-looking images. This partly results from us trying to emulate the style of those trailblazers who inspire us. If you are a fan of, say, Annie Leibovitz, then your photos are likely to imitate her fabulous work. On top of that, because they have not developed their own style, novice photographers tend to shoot very similar photographs. That is not only through a lack of skills. Even when they do learn to override the automatic settings, novices use mostly very similar beginners' cameras and, more importantly, kit lenses that, although okay quality, do restrict creative possibilities.

Others' Opinions Are Holding Us Back

Digital photography, more than any other art, is restrained by pressure from sometimes aggressive opinions of the internet. The online world has a vocal minority of conservatively opinionated, self-appointed critics whose objective it is to constrain photography and prevent it from expanding.

Take, for example, street photography. I have read that you mustn’t use a telephoto lens. But, that is nothing more than opinion. Others state that images of people talking on cell phones should be dismissed. Why? Those are perfect examples of contemporary life.

The worst sin, according to the self-appointed experts, is photographing homeless people begging for alms. Unkind assumptions are instantly made about the photographers that record images of the homeless. The photographer is clearly taking advantage of their misfortune. Yet, isn’t photographing and raising awareness of social injustice is surely a worthy thing to do? Furthermore, most photographers will do some kindness in return for taking the photo. Perhaps we should question the motivations of those who want to sweep the depiction of homelessness under the carpet and, instead, insist we only present a sanitized version of our society.

Why You Shouldn't Listen to the Critics

Historically, it was magazine editors, especially in fashion magazines, deciding what style was worthy of publication. They served as a restrictive filter, preventing experimentation in new areas that did not fit with their opinion; they decided what photographic styles should be fashionable. Now, however, their influence has diminished.

Although imperfect, the internet should be a far more democratic driver of taste than the critics. Though magazine critics have been replaced by those opinionated people on the internet who think they are entitled to decide what is and isn't acceptable, fortunately, they have an overblown belief in their influence. Style becomes fashion not because of the say-so of a few noisy individuals, but of the masses.

But there are two problems with that. Firstly, as in any field of art, the vast majority of viewers will choose the low-brow, easy-to-like over that which is more challenging. Whether it is TV, books, music, wall art, cinema, or photography, the majority are more likely to watch, read, or click the like button if the art is easy to comprehend. Furthermore, those producing the art are most likely to attempt to please their audience. This leads to an overall lowering of quality. Worse than that, styles stagnate into comfortable mediocrity.

Secondly, visibility, and therefore broad approval, is skewed by commercial interests. For example, social media companies are not democratic. They sway the number of views posts get to maximize their own profits; unless you pay them, if you want your images to be seen more widely, then you must bow to their optimization algorithms. To reach the widest audience and have the most engagements, some say Instagram requires you to post fourteen times a week, although others claim it's at least once per day. Either way, can any self-respecting photographer produce that amount of quality content? Not many can. Consequently, top-rate images posted on Instagram are swamped by mass-produced cell phone snaps. As a result, unique styles struggle to breakthrough. So, maybe we should seek other means of sharing our photographic art.

How to Develop a Style

If you want to develop your own style then, firstly, accept that there is nothing new under the sun. Find out what is already out there. Do research. Then experiment with different techniques. Do this by looking at other photographs and discovering what you do and don’t like, work out how the images were composed, captured, and developed, then try to repeat that. Also, read articles about photographic techniques and, especially, interviews with photographers. They usually contain great hints and tips.

Next, go out and try combining those different approaches in new and creative ways. Don't be afraid to fail in your attempts. The worst that can happen is that your work goes unappreciated, or some troll will criticize it in the comments. Although, that might not be a bad thing. After all, van Gogh’s paintings were dismissed by his contemporaries. However, experimenting may result in you being ahead of the game, and starting a new trend in photography.

By experimentation, you can discover photographic styles that suit you. Only when photographing to meet the requirements of a client’s contract is it necessary to restrict your style and shoot what they expect. Even then, they have probably commissioned you because they know and like your style.

Finally, the images I included for this article were a style experiment. Some I like better than others, and so will adopt those techniques I prefer and reject the others. Have you developed your own style? Or, is having unique originality not something that concerns you? It will be interesting to hear your opinions and see demonstrations of your style in the comments.

I'm not sure developing a style is important, Ivor. However, it is if you wish to rise to the top of the industry.

Quick question, where do you discuss "why it's so important"? Did I just miss something really obvious?

I think that most people want to improve in what they do, and produce work that is compelling for the viewer. By developing a style, one can find out what works and what doesn't. For example, a landscape photographer might stick to one focal length, aperture, shutter value and subject distance, choose similar terrain, the same tripod height, and the same time of day, and use the same filter. They then might decide upon a similar composition for all the shots, and the same post-processing. Each of those elements will have been mastered, and together give an overall style that makes the body of work cohere.

The importance is being focussed on the experimentation, and discovering what works best for the photographer. Sorry if I didn't make that clear in the article.

Thanks for the comment.

I guess the question "where do you discuss "why it's so important"?" Was unclear.

Maybe you should edit the title or the article.

The issue with photographing people who are homeless — it's one of consent and power. Many people in that position cannot escape from the photographer, there's nowhere for them to go to avoid them. It's another thing entirely to have a conversation with that person in an effort to understand them and empathize with their situation[s]. It's the old adage "it's more important to click with people than click the shutter."

If you don't give a damn about the person, the photograph will essentially be utterly meaningless. So why bother?

Hi Jay, as I said in the article, "Furthermore, most photographers will do some kindness in return for taking the photo." Thanks for expanding on that, you are right.

Whilst technically we can photograph almost whoever we like in public, I have my own set of rules regarding who I think is OK to photograph and who isn't. I certainly don't take photos of homeless people or anyone else who could be seen as vulnerable. It's tricky knowing where to draw the line but I'm certainly not one of those photographers who would happily walk up to someone and shove a lens in their face.

Igor for me your article is very timely and informative. I have always enjoyed taking pictures over the years with point and shoot cameras and just Got my first entry-level DSLR a year ago. I have upgraded my DSLR and purchase a few lens to upgrade my image quality as you stated in your article which can hold people back. My only goal is to become a good amateur photographer and I have recently been trying to find a style that I gravitate to and also produce them too. So… this article was very helpful to define some of the questions I have. Cheers and thanks!

I'm so glad you found it useful, Richard. Thank you for the kind comment, and all the very best for finding your own style.

Do it because you like it and because you want to do it for your own personal grow. If you do photography for the sake of showing off, winning competitions, or because you like someone and want to be like them you'll never get there. If you like sports shoot sports because you will have advantage over people who doesn't know much about it. If you like landscapes and hikes shoot landscapes because you enjoy being out and connect with nature. Only then when you do one thing and do it properly you'll be able to achieve things others wont. Our time is limited, so is our budget. If you decide to do bit of everything you wont be more successful then other. You can develop your style by watching tutorials and take from everyone a bit that suits you. And as last thing....try to think outside the box....don just copy others...try to learn from mistakes other making and try to see world around you with different perspective...do not follow styles of popular stuff...

Thank you Zdenek.

The not listening to critics and opinions is important. I'll take it a step further and say that when it comes to aesthetic, don't listen to the opinions of other photographers at all if you want to develop any kind of personal style. Aesthetic appeal is entirely subjective.

If your goal is to find a niche in a box built by others, then by all means, seek the aesthetic approval of other photographers. That goal is as legitimate as any other. But just realize that you're morphing your personal aesthetic to mimic that of others.

Personally I like the Peter Coulson approach-- Take photos that you love and don't listen to anyone else.

I believe in exactly the opposite: I think Hitchcock said that style is nothing but self-plagiarism. Particularly in landscape photography: when you recognize strong"style", you know you are bound to look at myriad of the same-looking photos, very boring.

Thanks for the comment, Drazen. Using the example in my article, looking through Don McCullin in Africa, there are similarities between each photo, but the subject is different in each case. Likewise, Most people would not call Ansel Adams' photography boring, and many of his Yosemite images do fit to his style. For me, developing a personal style helps one to break free from the "myriad of the same looking photos" that can be seen on the internet. Adding continuity doesn't have to mean making all the images will look the same, but differentiates yours from the others'.

Every person has traits of personality, so whatever you do will have some trace of you. If you let your personality develop naturally, it will still be present and recognizable at least to some extent.

However, if you "work on your style", "select your style", or do any other deliberate action to force yourself away from your natural inclinations, you are pushing yourself into "categorisation", predictability and ultimate boredom.

The only way to "work on your style" is to let it go, work on your photos and let style develop by itself, almost unconsciously.

I am pretty sure Adams didn't work on his style or selected his style, he was simply making photos as he liked.

Ansel Adams, along with Fred Archer, actively worked on and developed the zone system, which became an important part of his overall style, as was his patients in capturing the shot. Just as great musicians and artists develop their own styles, I believe that so too should photographers. That does not mean rejecting your "natural inclinations", but analyzing, learning and growing from them.

Ok, we can come to conclusion that we have diametrally opposite approach: you believe style needs to be found by organised, methodical and rational approach, while I believe style needs to find you.

That doesn't mean you mustn't analyse or study what other do, but only out of curiosity and based on what you like and feel, not based on rational needs, becaztoo much ratio kills all good things creative domain.

I think there is probably room for both approaches at the same time, Drazen, and they can go hand-in-hand. Thanks for the interesting conversation.

@jay turner:

"it's more important to click with people than click the shutter."

Rubbish!

I’m not “there” to click with anyone. I’m there to capture lightning. There’s precious little time as it is to effectively do that as lightning happens … and it’s gone.

Clicking with an individual is great if you’re in the midst of an essay project, ala Lange, however, if one has but an hour or so to just shoot … take the shot, skip the “relationship part” and move on.

Neither will be the poorer for it, and you may, or may not have captured the flash you were hoping for.

Anyone whom shoots enough, over a long enough period of time, will inevitably produce their “style”.

Now, as to the quality or value of said style … that is another door opening to a different room altogether.