Editorial photography is a wonderful place to flex your muscles and test your abilities. You don't often get to shoot such variety and have such control on a single assignment. Over the past couple of weeks, we've discussed ways to approach the photography of your first assignment. Check those out here and here. This week, we'll be taking a look at getting your foot in the door and what to charge.

Outlet and Audience

You won't see National Geographic just yet. Getting into editorial work is somewhat of a Catch-22 in most places; you need published work to get published. There are plenty of ways to make this happen. Personally, I started with small community magazines and blogs. I still use these outlets for work that I want to be extremely creative or experimental with. Look around your community. No doubt there will be small publications, newspapers, blogs, or other outlets that interest you. Start there and work hard at your first assignments. Creating your own blog and uploading self-assigned work is another great way. Even if this is simply something of personal interest, promote it to parties who may be interested and become active in their worlds. This will establish you as someone they may want to work with in the future.

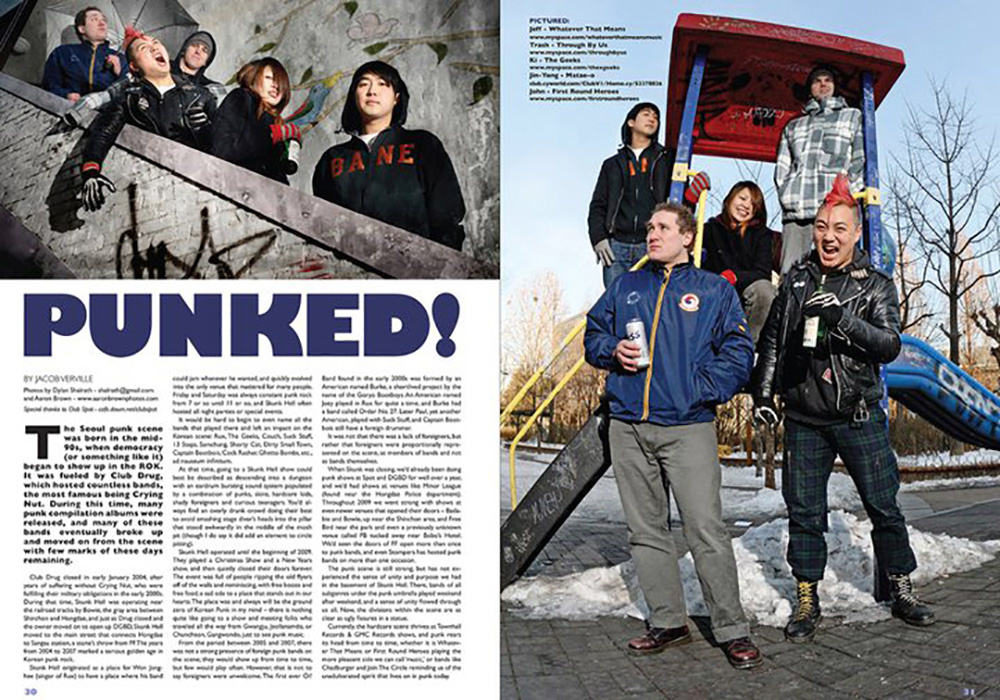

This was my very first editorial assignment. It was on punk music culture in Seoul and involved various members from punk bands all around the city. I was still learning my off-camera lighting and aiming for a gritty aesthetic. I had this in my head. My editor had no trouble assigning me this work after I showed her some of my personally created portfolio. However, she evidently thought 11 a.m. was a fine call time for punk band members and we waited a good three hours to get started (even when we did, prying the bottle of whiskey from the hands of our subjects was a tough job). Once everyone finally arrived, it was time to get started and make some frames that gave a sense of punk culture. We both worked really hard (she was present). Perhaps not the most refined frames I have ever made, but for my first assignment in a community magazine, I was extremely proud at the time. It was a tough job, but we both felt like we got the best from what we had.

Money

The question on everyone's lips is money. I'm going to be honest here: I slogged a couple of years without a cent. That's how it goes. As a starting photographer, you need tear-sheets. These are your foot in the door. Work your posterior off at any chance you get and build a fantastic set of tear-sheets. This will give editors a level of trust in you that will enable paid work and for your pitches to be taken seriously.

There are basically three ways to get paid in editorial photography. The majority of magazines have a rate. This could involve a certain pay per picture or picture size and a pay per word. Generally speaking, most of your inquiries will come in this way. You will be given a short brief, a rate, and a deadline. This makes things easy as you simply take it or leave it. Depending on the publication, you may receive $10 or up per published image. This payment style is common for travel and lifestyle magazines. Some magazines may also have a rate for a particular consignment (this could include photos and text). Unlike per-image rate tables, this style is more likely to have a budget for expenses, which would need to be discussed with your editor.

Where things get difficult is when the editor asks for your day or half-day rate. You have to be extremely wary. If you are lucky, your first assignment will not involve you deciding what your work is worth. If you have to, however, there isn't much beyond that. Decide what your work is worth in the context of the consigning magazine. WIRED has a slightly different budget than a small magazine in downtown Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Keep this in mind when you are asked. Who are their advertisers? Who are their readers? What is their distribution? What is the going rate for photography in the city? What are you worth at this stage in your career? Answer all of these and you will be closer to an answer for how much to charge. There is really no answer beyond the hard slog and learning by trial and error.

Doing the Writing Can Help

A lot of magazines now, particularly in the travel and lifestyle industries, love to get everything done in one hit. If you can write as well as shoot, you'll be one step closer already. Learning to write, even in a basic manner, can really help you. You don't have to be Paul Theroux right away to get into travel writing, but being able to spin a narrative people will read may mean the difference between getting the job and losing it.

Learning to write can be a difficult task for visual people, but there are a lot of great ways to get a head start. Many online courses are available, like Matador U's course on travel writing, or attending a writing class at a local school. This can really help you get in the door with the current market. This is not to say that mediocrity on either side will work for you, but rather that you should work towards competency in more than one skill in order to land jobs that will further your career.

My writing may not stand on its own and impress scores of people to buy books simply because I have the byline, but I have gained enough skills to have my words published alongside my photography in several publications. Above was one of my first articles, a simple journal for my images that I shot in the countryside nearby Phnom Penh. The editor was looking for something off the tourist path and I provided it. Take opportunities like this and make the best of them. They can provide unimaginable opportunities in the future.

In Conclusion

In order to wrap up this series up, I thought I'd offer one more anecdote. This isn't easy and I want to impress that on you. There is no shortcut to this work.

The one time I have completely disappointed an editor was more recently. The fact that it was a low budget publication was irrelevant. The fact that it was the busiest week of my career was irrelevant (I'm busier this week than I have ever been). The fact that I had only thirty minutes to shoot a cover and 8 internal images was irrelevant. The fact that I failed what my editor had asked is. Don't fail. Understand what it is you are needed to do. Understand that your situation doesn't matter. Understand the deadline and meet it. That will get you more work. That, and stellar performance while you're at it. Do it, do it on time, and knock it out of the park. All the best!

Those photos are making me nostalgic! My man Hae Man No Kwon with the drum, the Hongdae slide! and is that Velvet Geena I see?

I actually believe that's Trash from "Whatever that means." Velvet Gina never had hair that long, did she?

ah you're right. Looked like her on the left, but not in the park.

"The fact that I failed what my editor had asked is. Don't fail."

I love this whole series, but isn't a fear of failure like taking a step back? Having moments when we fail teaches us important lessons, does it not?

Absolutely. I encourage you to do it every day. You fail, you learn. That's the best way to learn.

However, on someone else's time and money, it's best to be over-prepared and not fail. Within the context of doing editorial work for a paying client, don't fail. That's what I'm saying here.

I beg to differ when comes to business. I got paid even in the beginning sometimes not so much, sometimes quite a lot. Even when I started 30 yrs. ago I would not even consider $10 a photo fair compensation no matter how small the client. There is no way you can operate a sustainable business for those kind of rates. If you write you need to be compensated for the photos and then again by the word. Better to get your business advice from A.S.M.P. or APA or EP or read John Harrington's "Best Business Practices For Photographer's other wise it's a race to bottom and publisher's can't believe their luck. Find out your cost of doing business, what it costs you do business and realize that if you don't meet that cost you are losing money. Remember that once you are known as cheap you will never be able to raise your rate. Write about your photography all you want but save your business advice.

Addison Geary is right-on-point! Even though you’re building your portfolio, join ASMP.org or APAnational.org as a student member to learn about the business of photography. Purchasing any one of John Harrington's photo/business books will pay you lots of future dividends: “MORE Best Business Practices for Photographers.” Other excellent business and legal resources for new and veteran photographers include www.theCopyrightZone.com and www.Photoattorney.com.

I’m not a fan of photo business advisers who skip mentioning the importance of timely registering all your assignment & stock photographs with the US Copyright Office. BTW, registration applies equally to non-USA-based working pros! If you own the rights to your photographs, then registering them will help reinforce your legal rights against infringers and any licenses you grant to third parties. Again, visit ASMP or APA sites for free tutorials, or purchase Harrington's book. The Copyright Zone authors also sell an excellent book; their 90-minute YouTube webinar is a must-see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yi9353BTM_s.

There's money to be made in Editorial---> It's how you go about doing it. I have managed to surpass my old salary at my job that I used to work before I went Full-Time doing editorial. Now it took a lot of TIME and I had to do a lot of SMALL publications (which are now my bread and butter shoots). Now, I'm doing advertisements (local, state, national) and national editorial work all because the portfolio (tearsheets) are reflecting the experience. I still shoot my local mags because 1. They gave me a shot 2. Give me full creativity 3. REALLY EASY WORK 4. Allows me to save money and pay bills.

Keep Working Hard and NETWORK! :)