Multi-light setups can seem complex and intimidating for several reasons, not the least of these are all the variables involved. Where do you put the lights? What power settings do you use? How do you balance everything? What if there is ambient light from other sources? Then there’s the cost aspect. How can I afford enough lights for these complex set-ups? Luckily, I’ve made things complicated for myself so I can make them as easy as possible for you. Let’s break down these three shots and find out how you can light a complex scene without making your wallet cry and, hopefully, without too much hassle.

I’ve had the idea to do a Film Noir inspired photo shoot for a while now—we’re talking years—and I finally found the perfect location: the Nocturne Jazz Club in Denver. It has an art-deco vibe that makes for beautiful visuals and matches the feeling I wanted to create.

I have a general policy of scouting any location before I shoot there so I can be as prepared as possible. Since the venue is an hour away from home and I have a busy home life, I decided I’d do my scouting the lazy way—on the internet. I don’t recommend this as the sole way to plan a lighting scenario. If there is any possible way to get yourself to the location during the time of day you plan to shoot, do it. You’ll be better prepared.

So, I scoured the internet searching for photos and video from every angle I could find. I planned my shots based on the storyline and location of the set elements and architecture inside the venue. Once the shots were planned, I needed to decide how to light them. I wanted the light to be dramatic, an updated take on the Film Noir style from the '40s. I knew I would need the light to highlight my subjects as well as the showcase the venue while maintaining an appearance of reality. I would be working with four actors, so light would need to be carefully placed to be both flattering and believable.

To get the kind of light that would fit this vision, my studio partner brought two constant light sources that would mimic the club's lighting, the Yongnuo YN600L and I chose a Canon 580 EXII speedlight for extra power, with a modifier that would let me give very directed light and control spill, the 26" Westcott Rapid Box.

The first thing I did once on location was get my blocking down. The actors were placed in position so that when we introduced the light, the camera and tripod would be set up and I'd have the perfect angle to capture the images I'd sketched.

After that, I figured out what settings I would need to get a proper exposure of the club with just the ambient light value of the room. Because I wanted the appearance of a nighttime setting, I underexposed just enough to darken the image without losing shadow detail that would come in handy in post-production. This meant that my key lights would be what made the actors stand out from the background. This helps me control where there viewers eye goes in the scene.

Once I had the overall ambient exposure where I wanted it, I began to introduce my constant lights. Constant lights were chosen to mimic the constant lights of the stage and bar, and also because they would require less attention once set up. Turn them on and go, no messing with triggers or modifiers. The price point doesn't hurt, either, at $100 a pop. Since these lights have a remote controlled dimmer, it was easy enough to set them to a power that would work. The trick at this point was to find the sweet spot between power and distance. I wanted the lights strong enough to give me a proper exposure and rim light, but not be in the shot or, at least, in a place that I could easily remove or composite them out. Most of the time, the constant lights were just barely out of frame.

While setting them up, I was trying to mimic the angle of lights that existed in the venue, such as the spotlight and accent light, as well as the bank of lights that hung over the bar and the excess light from the stage.

After setting up the constant lights, I put my flash into play. For this shoot, I used the speedlight and one of my favorite modifiers to take on location, the 36” Westcott Rapid Box. I chose this set up, even though I brought an Alien Bee’s 1600 and several modifiers with me just in case, because it’s light, it packs small, it’s easy to maneuver in cramped spaces, has no cords that need to be taped down, and is more than powerful enough to give me what I need. This would work equally well with a more cost-effective speedlight, but this workhorse has been in my bag for more than seven years, and it’s my go-to for all kinds of location lighting.

Once everything was in place, I could focus on directing the talent and crew. Sometimes lights need to be maneuvered ever so slightly, or I needed the talent to adjust their pose or expression or ask the makeup artist to touch up lipstick, but all of that becomes a breeze once the foundation of good light is set. It’s the foundation that makes everything else possible and creates the mood that will make or break the image.

Photograph 1: The Lady in Red

These light sources were chosen to mimic the lights hung above the bar and light spilling toward the bar from the stage. I wanted this shot to have a Film Noir meets Old Hollywood style that would showcase the beauty of the actress.

The Lady in Red actress Janelle Ames and Bartender actor Matt Block at Nocturne Jazz Club

Both lights in this set up are constant lights to give the feel of Old Hollywood meets Film Noir

Photograph 2: The Huntress

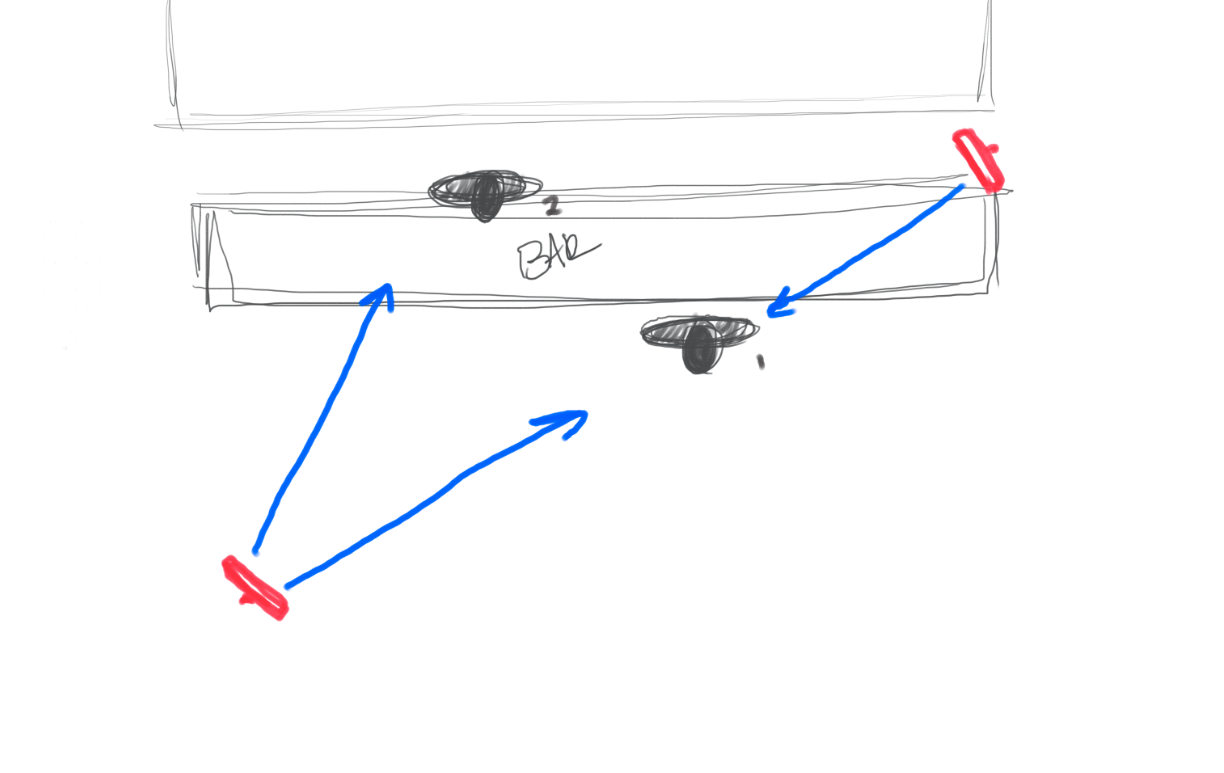

This photograph needed to look moody to showcase the disgruntled main character, and make it clear that the Lady in Red was sizing up the main character. I wanted the bar to have light very similar to the first shot, so the rim light stayed in the same position while the original key light was moved toward the camera and behind the stairs, keeping the light direction very similar to the new key. This allowed me to keep some light on the bar and gets subtle light on the details like the bottles and bar design. The key light for this shot was the speedlight through the Rapidbox from the direction of the stage to give my main character a believable light source that fit the mood of the scene.

Actress Janelle Ames, Actor Matt Block and Model Chase Watkins

Enjoy my super awesome light sketches.

Photograph 3: Only the Lonely

This photograph, taken from a new angle, required a different light set up. With the full cast of characters, each person needed to be lit in a way that made sense for their role. The Jazz singer, reminiscent of the great Billie Holiday, would be lit by the stage lights in real life, so one constant light was placed high and angled down toward her. The Pianist would be lit by the fall-off of the stage light, and by accent lights from the side of the stage, which are warmer in color. Constant lights were used for both of these purposes since they aren't as powerful and would provide believable lighting.

The key light for this scene was, again, the speedlight through the rapid box. I wanted the main characters to have a bit more punch and for the light to be more dynamic without spilling across the whole foreground, thereby keeping the focus on the main characters.

Joining our cast of characters is singer, model and actress, Ariel Robinson

Now that you know how I approached getting these shots, here’s how you can do the same thing.

Blocking

Blocking is getting your subjects positioned for the shot. This is important because it lets you get a feeling for where the lights should be placed.

Check Ambient Exposure

You want to make sure that you’re nailing the ambient exposure for several reasons:

- So that the balance between the ambient light and the light you introduce into the scene makes sense and fits the mood you’re trying to achieve

- So that you don’t overpower the subject with too much light. (I like to keep my shadows open enough that I don’t lose detail. It’s a lot easier to darken shadows in post-production than it is to rescue detail)

- So that you have a solid baseline to build your lighting up, rather than trying to compensate for a poor exposure later.

- So that you have a backplate of the scene in case the location or venue restrictions (or any other mishap, really) makes it necessary to composite something out…like the head of your grip popping out from behind a table, or a stray light stand.

Add Lights

Now you can begin placing lights in the scene in a way that makes sense for the visual language of your shot. My personal preference is to mimic light that would naturally be in the scene, as I don’t like images to look overly lit, but follow your own aesthetic here. For constant lights, the power and distance from the subject will vary depending on the circumstances of each shoot, but follow the same rules as all light. Without additional modification, closer equals softer (size relative to the subject) and stronger, farther away equals harder (relative to the subject) and weaker. Make adjustments to distance and power as needed for proper exposure, mood, and fall-off.

I like to take a photograph after each light is in place so I can make any adjustments to the exposure, angle or power of the light before the next light is placed. Should you choose to use all flashes, the same rules apply.

Take the Photo

Now you get to start getting into the scene, directing your talent, and making any minor adjustments that need to be made. If it’s possible, I absolutely recommend tethering while you shoot. This is not a must in any way, you can still use this process to get great complex shots without tethering, but setting up photo shoots like this one require a lot of leg work, from scheduling and paying location fees to managing a crew of people and all that jazz, so the last thing you want is to walk away thinking you’ve got the shot only to realize when you download the files that you’ve missed focus on the most important shot or some other detail that renders all your other hard work moot.

As a side note, for tethering, I use my ASUS laptop with solid state hard drive, Capture One Pro, and a TetherPro USB cable and JerkStopper Camera Support from Tether tools. I find that being able to see exactly what I’m getting, and sharing those successes with the crew when there’s time, keeps everyone excited about what we’re creating, especially me!

All the light related gear I used to get this image totals just a little over $800, but you can bring this price way down by substituting a more wallet-friendly flash, like a Yongnuo or a Godox, and land somewhere around $500 for the constant lights, the flash, modifier, and light stands, which isn't a bad place to be price-wise.

Conclusion

Getting what appears to be a complex light set up starts with planning. Forethought will get rid of many of the obstacles that might present themselves when you're shooting on location. But, it doesn't have to destroy your wallet or drive you crazy. If you're patient enough and work methodically, building you lighting base from the ground up, you can create almost any light scenario with almost any light source, from a flashlight to the most expensive studio strobes and modifiers.

can you please explain in a bit more detail wat is ment by "blocking", thanks

Sure thing!

Blocking is a term that comes from theatre. During blocking, the cast runs through scenes so they can practice where to stand, angles, etc. This gets placement down and helps the stage crew with timing and light.

When I'm shooting and lighting a scene with several people in it, I like to do the same thing, getting people into position so I can get their poses and my camera angle down, but also so I can fine tune the lighting.

I hope that helps!

Great concept, well produced and nice outlined. Really liked it! :-)

I appreciate that, Anders, I'm glad you liked it!

Great article! Wonderful examples! Top notch images!