From an early age, Bertie Gregory was sailing, surfing, swimming in the ocean. He was always outside, taking in nature. When you spend that amount of time outdoors and in nature, you gain an appreciation for it by osmosis. Even in England, a place not known for wildlife, he was able to appreciate it.

"Things like deer, kingfishers, and buzzards and things like that are not huge, charismatic, sexy animals, but I was completely obsessed with them. I thought they were great."

As a child, Gregory realized that if he took pictures of nature, it was a great way of explaining where he'd been when he missed out on social engagements. But it was also an opportunity to get other people excited about things that he was excited about. Then, he started entering wildlife photography competitions in the youth categories and started winning some.

Gregory ended up getting an opportunity to assist with the renowned photographer Steve Winter. Winter is National Geographic magazine's big cat guy. He shot big cat stories for National Geographic that were iconic for wildlife photography. He also photographed Apple's "Snow Leopard" background. Assisting with Steve Winter opened the door to the National Geographic family for Gregory.

Now, Gregory's year is split in two. Half of the year, he works on the BBC Landmark series like "Planet Earth" or "Frozen Planet." He is hired as a camera operator for those shoots, so all the locations, animals, and behaviors are pre-produced.

"As a camera person, I'll get rung up, and they will offer me a shoot. That will normally be four to six weeks, and that'll be three to four minutes in the film."

In the other half of the year, Gregory creates a series for National Geographic. With his series, he is a producer, and he hosts the programs. These projects are his babies.

"I'll research them, and then, I'll pitch them to National Geographic. I follow it by working with a big team to get it edited, color corrected, and sound design, and all that stuff."

As a show creator, it's about finding that balance. Gregory knows an amazing story needs a cool landscape, exciting animal characters, a cool piece of exciting behavior, but most of all, it needs a purpose.

"I think gone are the days where we can just tell sort of Garden of Eden type stories, where we can pretend that these animals have lovely lives and are untouched by the hand of man."

Morally, he does not think it's right to continue to tell those types of stories. His goal is to get people excited about the wild places that still exist on our planet and talk about the impact that we're having on these environments.

Filming Wildlife With Drones

Over the past decade, drones have primarily been used to shoot cheap aerials. Improved battery and gimbal technology has brought substantial improvements, so now, we can go beyond filming just pretty landscape shots, we can film animal behavior. The key to filming natural behavior is to leave the animals undisturbed over a period of time. A stronger gimbal that can hold larger lenses combined with greater battery life can accomplish this goal. Now, Gregory can take a drone and film the behavior naturally on a long lens at high or ground level. This gives you much more authentic footage to work with when you are cutting a segment.

"A shot of an animal running away is rubbish from a cinematography perspective, but obviously, morally, it's also not something we want to be doing."

Shooting in ways that do not disturb the animals is vital. Drones have the potential to be a noisy, fast-moving tool that you could chase animals with. You have the potential to cause a lot of disturbance.

"We do a lot of research into how the particular animal we're trying to film might react. We talk to scientists, and we look to see if anyone has flown a drone around that animal before."

Online people often take issue with people flying drones near wildlife. But Gregory's view is that the drone pilot is the one disturbing the wildlife. There are a lot more variables to consider. The degree to which an animal will react to a drone will vary dramatically between species and even within the species. One animal might run away. The other animal won't care. Bertie always brings an expert who interprets animal behavior, so the first time they fly the drone around an animal, they can see how the animal reacts. The goal is to habituate the animal to the drone.

"When you're filming wildlife in the normal way, from the ground with a zoom lens, on day one of meeting an animal, you are not going to just run up to it from a kilometer away to 10 meters away and then stand there making a load of noise and expecting it not to run away. You'd never do that. So, why then do people think that that's a good idea with a drone?"

His process starts by being far away and slowly moving closer. That can be over hours or days or even weeks. Typically, he plans to have a large stockpile of batteries because he knows they need to keep the drone hovering a few hundred feet away from the animal for an extended period. Not close enough to film, but just so the animal is aware and getting used to that noise. By the end of a five or six-week shoot, the animal is so used to having the drone around it's just part of the environment.

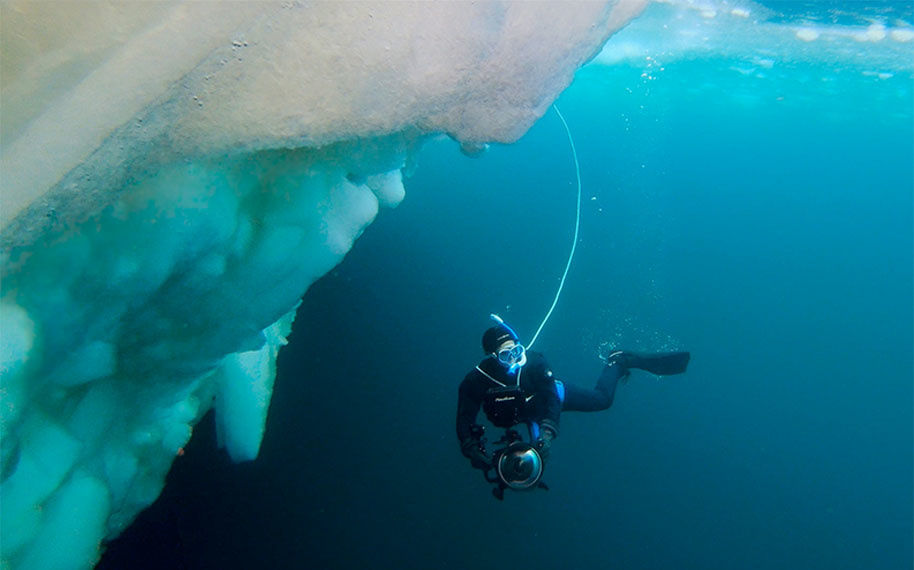

Filming Underwater

Using a camera underwater requires a level of OCD because there are so many little elements you've got to get right. It is essential to spend a lot of time trimming the housing. Bertie uses small weights all over the camera rig so that if you let go of the housing, it stays upright. That gets rid of a lot of the wobble. This process is similar to using a counterbalance on a tripod head on land.

Once you are underwater, your skills as a water person are essential. When operating a camera on land, you have to learn to walk with it. Underwater, you essentially are using the camera like a gimbal.

"You're swimming it round all over the place, and you've got to get your moves to be really smooth. That all comes from just the time in the water."

Depending on your situation, you must decide if you will free dive with a snorkel or use full scuba gear. They both have benefits and drawbacks. The advantage of freediving is that you're moving fast. But then, if you need to go deep, you're limited by your breath. But if you decide you want to use scuba equipment, you have to consider the number of bubbles you will be making. A lot of sharks and whales are very nervous about bubbles. Each situation calls for a different diving technique. If bubbles are a problem, you can use a rebreather, a system that allows you to stay underwater and doesn't produce bubbles. But a rebreather is a technology that's a lot harder to use and potentially more dangerous.

"You've got to weigh up all the pros and cons of each of the different tools and figure out what's best for your situation."

Message to Wildlife Photographers

Gregory would like wildlife photographers, young and old, pro and amateur, to understand that we're all journalists. The goal is always to leave the environment undisturbed, leave nothing but footprints, or if you're underwater, leave nothing but bubbles.

"We should be environmentalists that want to raise awareness for the wildlife and get people to be excited about them, so it'd be a bit silly if, in the process of us trying to do that, we were then destroying the habitat."

That should always be the first consideration.

Lead photo by Becky Kagan Schott.

Photo number 1 by Greg Smith.

Photo number 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 by Spencer Milsap.

Photo number 7 is a selfie.

All images used with permission.

Amazing Article, Martin! Loved to read it. And I'm quite jealous of Gregory as well :D

Thanks Nils! Gregory gets to see some amazing things! very cool.