So, paying attention to light direction is vital. And by the way, I have used studio photographs in several instances here because they more adequately illustrate the concept I am discussing. The point of that, of course, is that concepts and principles cross genres of photographic work. They are basic principles.

Spread

When I talk about "spread," I am not talking about making a sandwich! By spread, I mean: "How much difference is there between the most brilliant highlight and the deepest shadow?" Will the range of light presented in the scene fit into the f-stop range of light your printer will print, or that darkroom paper will record?

A thing I have learned from many years as a film photographer is that the number of stops of light represented in a scene often exceeds the paper’s ability to print them. The film could record them, but they were beyond the ability of the paper to render them. Most often, the photograph would end up with either highlights with no detail—reduced to paper-based white—or, more frequently, the shadow areas in the image blocked up into a blob of indiscernible black with no detail. Often, the black with no discernible detail was the result of underexposure, and the lighter areas with no tonal separation were the result of inaccurate processing of the film. The absolute outside limit of tones that black and white darkroom photographic paper could—or can—render is five stops, and that is only if the darkroom worker was a very good printer. Color negative films and transparency films have an absolute limit of four stops or less, so we really had to pay close attention. Digital has fewer limitations, and if the photographer is using Camera RAW, the raw file is essentially a digital negative. Sometimes even blown-out highlights or blocked-up shadows can be recovered. Even so, we have to know what the limits of our media are.

When working with film, one of the things I have done for many years—decades, even—is to measure the light reflected out of the deepest shadow area and then measure the light emanating from the most brilliant highlight. If the difference between the two was more than four stops, an adjustment in the processing of the film would become necessary. I apply the same principle when photographing using digital means, but the method is different. What is necessary is to look at the histogram of the image since that will instruct us about which parts of the image will have no printable blacks—blacks with no detail—and which parts will be washed-out white with no detail. Blacks with no detail are called "shadow clipping," since detail in the shadows is cut off, or "clipped off." Highlight details with no detail are said to have "highlight clipping." As much as possible, it's a good idea to avoid clipping on either end. Looking at the histogram, if the diagram goes off to the left, you have shadow clipping. If it's to the right, there is highlight clipping. To a degree, these can be recovered in a program like Lightroom if you are using Camera RAW as your recording method. Some people will tell you that you need to move the histogram as much to the right as possible without clipping. My practice is to look at the histogram, and if the range of tones shows no clipping on either end, I go with that setting. There are, of course, more considerations to account for, but I am only talking here about the "spread of the light," not the other factors. Here is a typical histogram. And by the way, never trust the LCD screen on the back of your camera to tell you the truth about either exposure or image contrast. It will lie to you like a Washington politician. It’s fine to use them to check on your composition; however, they will not tell you whether or not your exposure is correct.

Here is a photograph I created a number of years ago, and I will not go back to this location because there are so many people there now that it's impossible to do really good photography there—at least it is for me. There is a whole long narrative describing my adventure in creating this image, and it involves rattlesnakes! But there isn't space here for that.

Suffice it to say that the range of light in this location was over fifteen stops, so maintaining highlight detail and shadow detail was a difficult task. Especially considering that I was using film—at that time there was no digital and so there was no HDR. This had to be managed in-camera in the field, and then in the darkroom using a specialized developing procedure. Again, there isn't space here to address that. Using digital and HDR can be—and is—an invaluable tool. Sadly, it is grossly overused and abused. But used correctly, and with discretion, HDR can yield excellent results.

Color

The last factor of light that needs to be considered here is light color. Of course, since most of my work is done for black and white printing, image color is of no consequence to me. However, when a color photograph is being made, image color is a thing that we must consider. Again, I will hearken back to the days of yesteryear, when there was no digital that would allow us to make great adjustments to the color balance of our images after the exposure was done. We used corrective filters on the front of the camera lens to get an image that was approximately right, and then the rest could be adjusted in printing. But even now, it's wise to be aware of the color of light. A canny worker in Photoshop or Lightroom can manage these quite easily to get the correct color balance. However, in my experience, the photographer is better off to select the correct color balance when the image is being exposed. Doing so will greatly reduce the amount of time one spends in front of a keyboard.

Combining Qualities of Light

One of my favorite things to do when photographing, whether in my studio or in the field, is to combine qualities of light. Photographing with the main subject material illuminated by direct sunlight while the background falls into shadow emphasizes the item being portrayed.

In this image, "Prince’s Plume," the light was coming over the edge of the canyon wall opposite me, illuminating this showy little plant. The extra treat that I wasn't aware of till the film was processed is that someone—an ancient pioneer, I hope—left evidence on the wall that they were there! I barely made the exposure before the very beautiful light shown here became a disorganized mess as the disc of the sun rose in the sky above the south side of the canyon.

I enjoy this photograph a lot. As you can see, there are several of the characteristics of light shown. Light direction gave definition to the ridges in the distance. Specular light is being contrasted against diffuse light, and the trees in the foreground were in lightly diffused light. If they were in direct sunlight, like the ridges in the distance, with the sun directly overhead, this would be a visual mess, and it would be difficult to figure out what was being said exactly. It's a lot like listening to music. If your favorite piece of classical music is playing, you will want to hear every layer of tone and every entry and exit in the piece. Now, if the same piece is playing but there is also a huge clatter of construction work going on outside your window, the message of the music will be lost in the clatter of random and annoying sounds. Exactly the same thing with a fine photograph. If the "clatter" of raw sunlight against the great details of the forest are all equally illuminated, the message we are trying to communicate will be lost in the clutter of clatter. Our job is to make as clear and well-organized a statement as we can make.

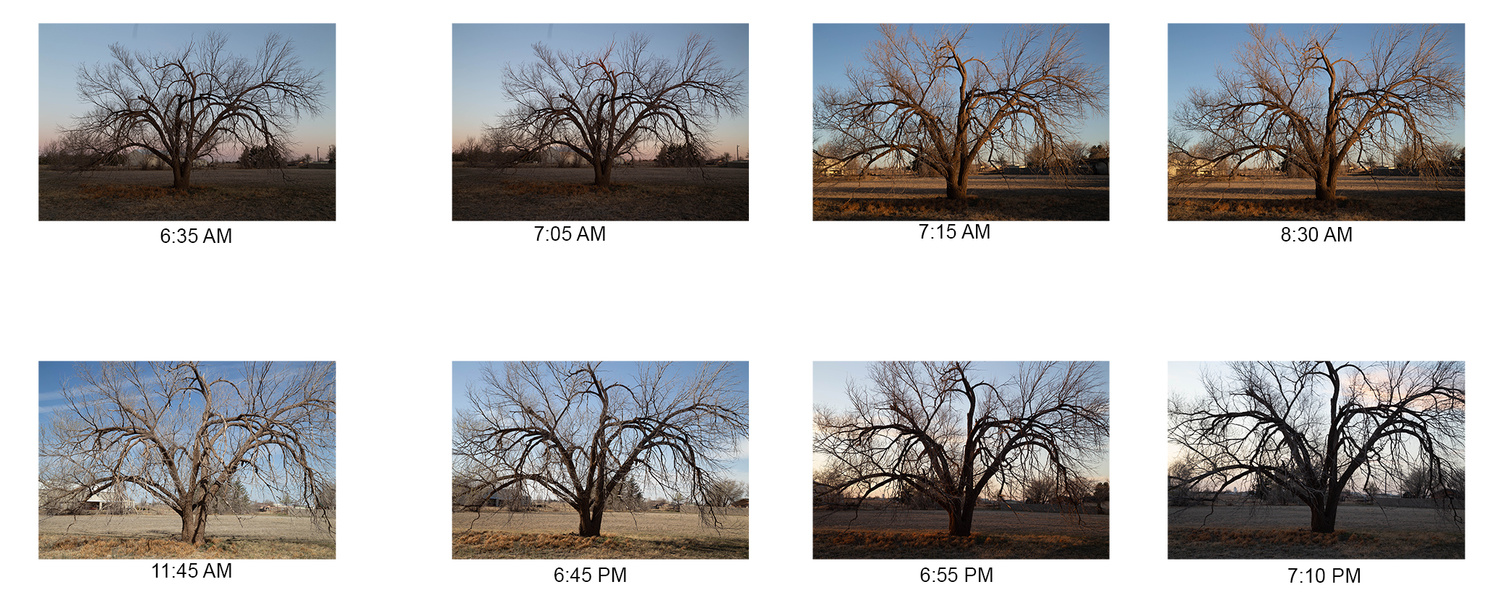

Here is a time study of a dead tree that I pass often when I walk my 2-year-old Golden Retriever, Gracie. It is not intended to show any particular beauty, only to demonstrate how the light changes across an object at different times of the day. Civil sunrise this day was 7:02. However, a building blocked light until about 7:15, when the tree came into full sunlight. Notice the streaks of light across the ground at 7:15, and in the next one, they are even stronger, and the light remains very directional. Notice that in the 11:45 image, when the light is directly overhead, the light pattern is pretty spotty and disorganized. Later in the afternoon, as the sun is lower toward the horizon, the light pattern becomes more organized. At 6:55, the sun has just cleared the horizon. There is no direct sunlight; however, it is still directional, while by 7:10 the light has become flat and is becoming uninteresting.

Mix It Up

So, as we consider all of these things, remember, nothing exists in a vacuum. In photography, as in all things, multiple factors are almost always in play. It is obvious from my time study that there is never just one thing that changes. Our job as photographers is to become a student of light. Learn what it is, what it does, how it does it, how it affects the subjects we are portraying. Many times, I see something that I think might be an interesting subject. However, the light is all wrong, and I think that if I returned to it—sometimes pre-dawn or at dusk—the light falling on it will portray it in a more powerful or delicate way. But our art, this art that we do, is about the light. It is always about the art. In my judgment, an interesting—or even beautiful—image can be made of almost anything, if the light is right.

That is a very good article. I need to find part 1. :D

Here ya go.https://fstoppers.com/landscapes/its-light-stupid-part-one-696005

Yeah part 2 very nice article Nathan congratulations.