There are tools that many photographers neglect and this is one of them. The histogram is criminally underused, possibly because it isn't all that intuitive to beginners, but once you understand how to read it, it can keep you from making costly mistakes.

There was a lesson I learned rather early in photography, but I didn't apply the right weight to it. In fact, I kept learning the same lesson — albeit less frequently — for a few years after I first started. This lesson was that the LCD on the back of your camera cannot be trusted. What I mean by this is that if you simply look at a picture you have taken on that screen, you can miss all manner of issues. For example, it's easy to miss the fact that your subject isn't perfectly in focus, or there is some motion blur, or you have blown highlights or crushed the blacks, and so on. The first two issues can be discovered with some zooming in, but the latter two have a far more reliable safety net: the histogram.

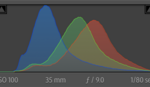

There are a few types of histogram, but the only one I use regularly is the luminosity histogram. If can learn to read this — which I assure you is easy to do — then a quick glance at it can reveal to you fatal mistakes. Not only can it tell you if there are any pure black or pure white pixels in your image (which would contain more or less no information), but it can also give you an overall sense of how well exposed the overall frame is by the position of the bulk of what's displayed in the graph.

Histograms are one of the driest pieces of education in photography, but are a worthy investment.

He forgot to mention that white balance also affects the histogram a lot (simply put).

I think it is not correct what he says about the RGB histogram and changing the camera settings to the natural view (at around 9:45): "Now, what you see through the viewfinder (EVF) is exactly what the camera's sensor sees..." This is never the case, as the RAW data has to be converted in several steps before an image can be displayed on the electronic viewfinder with its own (i.e. limited) colour space and dynamic range, and this is why.

While it is better to use the most natural settings for JPG in order to get closer to the actual data distribution, this does little good: if you change your white balance later in post-processing, the histogram will also change. Apart from that, his tips towards the end of the video to be careful not to expose too much to the right are kind of right, but you shouldn't bother, because you can always reduce the "exposure" (darken the image, move the histogram to the left) before switching to a vivid colour mode.

(edit). I forgot to mention that the histogram you see does not contain all the data that is stored. There is about 1/3 EV on the right side that is not shown (at least with Nikon cameras), a safety margin, I guess.

Let's say I'm shooting a scene that calls for ETTR. I would imagine that you'd want to later, in post, reduce the whites and highlights should your preferences call for it. Similarly, your preferences may also call for a slight change in the shadows too. Is this a correct assumption? I'm just trying to verify what I've been doing. My work flow has been merely to try and not have any clipping at all. Sometimes I wonder if this is even possible all the time.

If your scene has important details at both ends of the histogram, expose as far to the right as possible to get as much light (or information) as possible this way and have more margin to raise the shadows.

When the ettr thing came up a few years ago, I immediately jumped on it. But for a long time now I don't bother: it's not worth the effort. The gain is minimal, the danger of the highlights being cut off is greater. Pixel peepers see a difference, in real life one does not.

That's pretty much how I do it. ETTR then edit to taste/style.

I think if you are in a controlled environment and/or using lighting, you can mitigate the clipping.