Gonzalo Amat, who’s up for an Emmy for his work on Amazon’s Man in the High Castle, tells us the steps he takes to make a scene stand out in darkness.

In the wake of complaints that Game of Thrones was too dark for viewers to see, I was keen to get another opinion from an esteemed cinematographer. Who better than Amat, who needs to light incredibly dark scenes while also working with muted colors. This article is not suggesting that there’s a correct way to go about this, and Amat doesn’t have an opinion on Fabian Wagner’s HBO work.

This entire article focuses on a single episode of Man in the High Castle, Episode 10 of Season 3, “Jahr Null”. It’s the episode Amat might win an Emmy for, and it’s the stunning end to a fantastic season. There will be some spoilers ahead.

Amat on set, beside his trusty Arri Alexa. Some say that Amazon's Alexa speakers were named after Amat's camera.

Step One: The Camera and Glass

Amat had originally shot with RED Epic Dragon, but now the show is shot with an Arri Alexa SXT. There’s two interesting things here. Firstly, he’s losing resolution in exchange for (what some might consider) better skin tones and color reproduction. Secondly, he’s not using a large format sensor, opting for the tried and true Super 35 sized sensor. This is obviously a hit on low light. Interestingly, this camera has been historically refused by Netflix, who want true 4K instead of 3.2K.

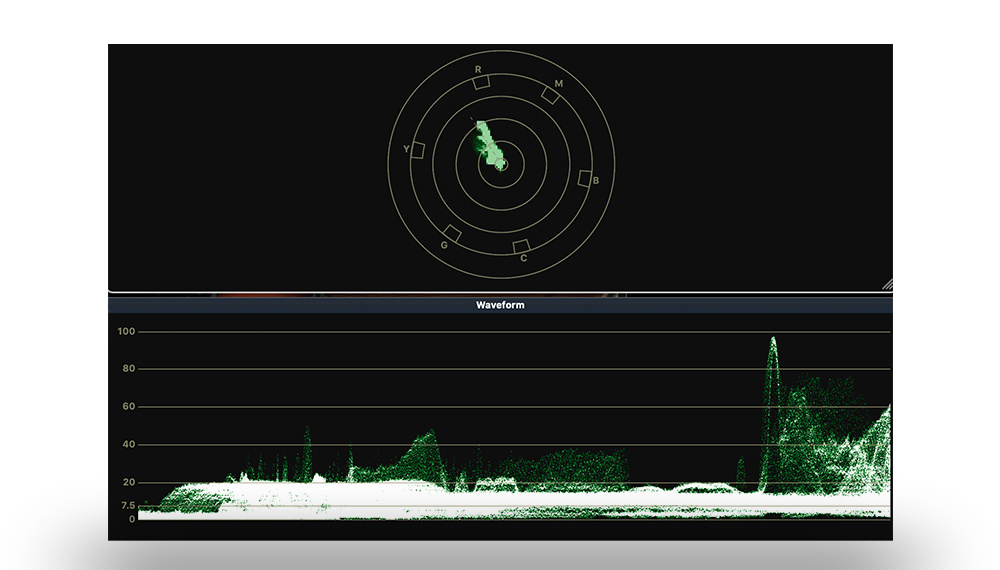

He usually runs the camera at 800 ASA (ISO for photographers). However, take a look at this scene in the mine (below). It was shot at 1280 ASA, so the camera is being pushed beyond its native ASA from time to time. Definitely not the Sony full frame some photographers/videographers would be used to, but respectively sensitive to low light.

Shot at 1280 ASA.

The crew is using Arri/Zeiss Master Primes. This allows Amat to really open up the glass but also ensure that he’s going to be tack sharp nonetheless. Generally he keeps the lenses between T1.4 and T2 (T-stops are a cinema equivalent to F-stops, but is a direct correlation to what actual light hits the sensor rather than a mathematical equation).

On the note of focus pulling, I was given some advice from Amat on how he likes to see a focus puller work. Firstly, he recommends sitting in the same room as the scene being shot. That way a focus puller will be able to see exactly how an actor is moving through the scene. Secondly, he likes it when a focus puller not only measures the distance from the sensor to the actor – but also the sensor’s distance to different points of the room. That way the focus puller has a general idea of the range they’re working with.

Dark, but you can see what you're meant to see. By lighting the background first, you'll be conscious of the contrast created when the talent walks into frame.

We can't really see the living room, but the audience still knows where they are in the living room.

Step Two: Lighting

So now that we know the camera has a good chance of seeing in low light. Let’s get into the heart of shooting in low light. I’ll run through the steps that Amat described to me.

1. Light the background first.

This is for three reasons. First, the actors aren’t on set yet and you’ve got time to play around with lighting ideas. Secondly, this allows the cinematographer to shape where the eye will be drawn to. A low light scene allows for more concentrated pools of light to show off certain background elements. Thirdly, you can make sure that nothing is too dark or lost in the background.

2. Then add practical light.

Practical lights would be the lamp on a table, candles, or similar. This is where Amat would work closely with the art or set design department.

3. Then light the actors and account for movement.

Amat says that while you’ll want to do tests with a stand-in, you can never account for how an actor will want to play out a scene. An actor and director might agree that the scene needs different movement than originally planned. That’s just something you need to be ready for, by having spare lights ready to go and allowing time for resetting lights. By lighting the background before the talent, you might have more freedom here.

It’s worth noting that Amat will often have two lighting setups at the ready, for when he needs to get a reverse shot in a dialogue heavy scene.

Aside from a light meter, having scopes and false color on your monitor can help you gauge exactly what's being shot.

Step Three: The Scopes

Sure, you can see what looks good to the naked eye, but there’s no lying in the scopes. When lighting the background, Amat wants to make sure that even the darkest parts are reading on the sensor. A luma waveform scope, and sometimes false color, would give him an accurate reading. “I start with the base fill” he mentioned. Apparently smoke also does a great job of leveling out the background.

In theory, this is what would have happened on the Game of Thrones set too. In post they would have crushed the midtones into the shadows, for that infamous night scene. The point is that you record as much information as you can so that you have more options later.

Step Four: The Look in Camera

The look and feel of Man in the High Castle is as unique as the show. It’s a blend of modern cinema with vintage aesthetics. What would the Nazi Party’s iconography look like in 1960s New York?

Of course, Amat is working closely with multiple teams to make sure the look of the show is always to his tastes. However he’s in a position to change things up on the day of recording too. Even if he doesn’t have a lot of light to work with, he can create contrast with other elements of the scene – the physical set in front of him.

“I’ll talk to the costume or art department before relying on DaVinci Resolve” he told me. Amat wants to paint a picture by concentrating on certain colors while desaturating or eliminating others. If there’s a color in the background he doesn’t like, he’ll ask to have it replaced. If a background color matches an actor’s costume too closely, he’ll have it changed to create more contrast.

Amat likes to get his color relatively close to the final result on set too. His monitors utilize a Rec.709 LUT (a preset that takes his flat image profile and adds contrast like you’d expect to see on a regular television). Then he takes saturation and contrast down about 10% in camera, and works closely with the DIT to get the right white balance to suit the feeling of the scene. Not necessarily trying to achieve the perfect white balance.

BTS shot of Amat.

Conclusion

“It has to be dark, but not confusing.” he explained. Amat is acutely aware of where people are watching his show. While I criticized the Game of Thrones production team for wishfully hoping that compression wouldn’t kill their work (when it sort of did), it’s the total opposite for Man in the High Castle.

Amat said he expects people to be watching on their iPad. To him, it’s not worth adding noise between your idea and the audience, when it could pull them out of the cinematic moment. In the color suite, they check it back on an older plasma screen TV.

It also affects how he frames a scene. He described how “sometimes a wide shot is too wide for a big TV in the living room” and how he works hard to ensure nobody is squinting to see what’s going on. While Man in the High Castle looks and feels (and costs) like full cinematic production, it would be a disservice to expect the audience’s home theater setup to match.

Bonus: How to Light With a Million Watts of Power

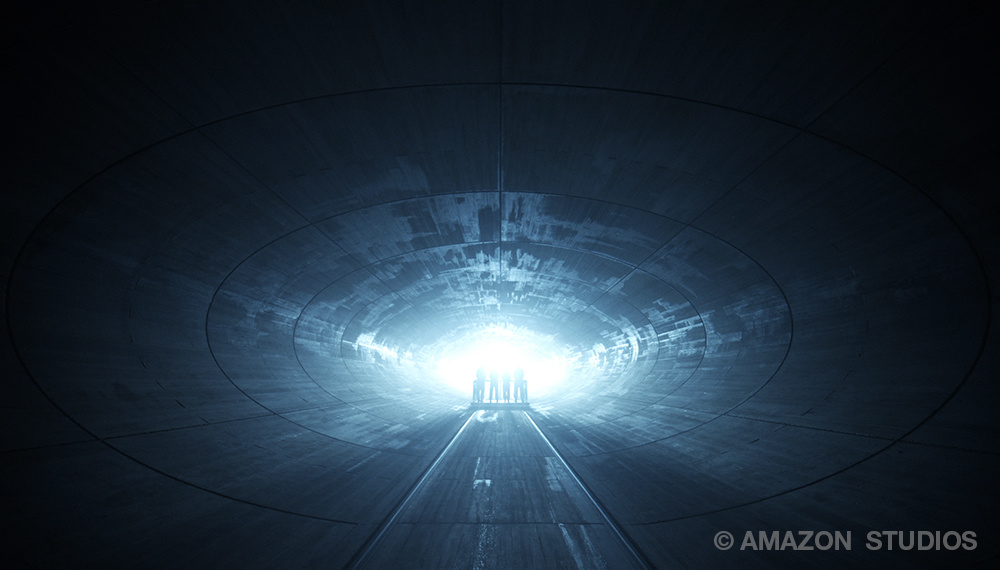

In this episode we get a glimpse of the Nazi’s mysterious machine. A long tunnel with a beam of light at the end, that can send people to another dimension. How did Amat and the gaffers light it?

They used 880,000 watts to power the lights inside the tunnel, which were diffused and bounced in such a way that it was blinding but the audience can still see what's going on. That included:

- 20’ high mirror plinth.

- x40 12 light HPL fixtures.

- x4 70K lightning strikes.

- x60 2K Martin profile moving lights.

Then they needed 60 Arri Skypanels for the control area. Combined with the air conditioning needed for the fixtures, it brings the total power needed to about a million watts (a megawatt). Pretty insane for a scene that’s got real contrast between bright highlights and deep shadows. I can only imagine the electricity bill.

880,000 watts of power, down the bottom of a huge tunnel.

Of course, Amat is only one person. While he has a wealth of knowledge, and he's up for an Emmy award, his way of lighting a scene is obviously his opinion. I hope this article helps aspiring photographers or otherwise, learn about the possibilities that they can avail of.

If you're a fan of Amat's work, check out his Instagram! Hopefully he'll be posting that Emmy award soon. Interestingly, he's up against Game of Thrones too.

Images used with permission from Amazon Studios.

Always a good idea to study cinematography to learn lighting. Photography books and even other photographers usually fall woefully short, compared to the sophistication movies require from the lighting department. From the gear to the constant lights to the obsession over light, there's a lot still photographers can learn from the people--the gaffers--who do lighting for a profession. We as still photographers may not have million dollar budgets, but we can sure learn a lot from the people who do, and are doing similar things: lighting people and scenes to record on digital frames.

A couple of points. First, using ASA versus ISO is more of a generational thing rather than a cinematographer thing. Second, ARRI Alexas are not less sensitive than RED cameras. The slightly lower resolution of the Alexa allows each pixel to be larger and therefore sensitive to light. 800 ISO might be its native setting, but it is often used at both higher and lower sensitivities. It is true that Netflix would not allow use of the Alexa, but that was only for shows that it originated itself. There was no such restriction on programmes it bought from other producers.