Following along on the path of the ABCs of photography, we reach D and the process that kicked off photography in the first place: the Daguerrotype. But what or who will join such an auspicious and founding technique?

Daguerrotype

The Daguerrotype was announced in August 1839, being gifted to the world patent-free by the French government. Developed by Louis Daguerre, with a significant dose of help from Nicéphore Niépce, it enabled cameras to produce permanent images. Niépce developed the chemistry to produce photographs, although they required very long exposure times. Daguerre improved the process by using iodized silvered plates that were subsequently developed with mercury fumes, integrating the plates into a camera and calling it the Daguerrotype.

The photographer needed a polished sheet of silver-plated copper, treated it with fumes, making it light sensitive, before exposing it in a camera. Mercury vapor was then used to develop the image, before fixing. After rinsing and drying, the plate was usually sealed behind glass. The resulting positives were highly detailed, but lacked any method for easy reproduction. This was in contrast to the Calotype, announced in 1841 by William Fox Talbot, which used light-sensitive paper (silver iodide coated) that produced a translucent negative. This allowed reproduction through contact printing, but the images were less detailed.

Daguerreotypes normally produce an image that is laterally reversed (i.e. mirror images) due to the lens. This is true of any optical instrument and is easily corrected by placing a second lens in the system; however, it appears this was not regularly performed because of light loss and so, extended exposure times. For translucent negatives, you can just flip the image, but this was not possible with Daguerrotypes. If there is any reversed writing in an image, then this is why! Daguerrotypes also provide a different viewing experience to contemporary photographs, because the image sits beneath the surface of the glass cover and almost appear to float. In addition, the viewing angle can also cause the image to flip from positive to negative (and back), all of which produces an immersive experience.

The Daguerrotype rapidly spread around the world. For example, the portraitist John Plumbe was working in Washington D.C. in 1840! Images had been produced in Australia by 1841 and Japan in 1857. By 1853, somewhere in the region of three million plates were being manufactured in the United States alone. The sheer scale and openness of the invention led to a whirlwind of innovation. Of particular importance were improvements to the chemistry by switching the sensitizing agent from iodine to bromine or chlorine (I'm guessing health and safety was fairly rudimentary!), which dramatically increased the sensitivity of the plates, thus reducing exposure time. The other key improvement was to the lens, with the release of the Petzval Portrait Lens. Up to this point, most photographs were restricted to landscapes and architecture simply because of the long exposure times. By improving the design, Petzval produced an f/3.6 lens, in contrast to the previous f/14 Chevalier.

By 1860, the Daguerrotype had all but died out. The wet-collodion process (e.g. as used by John Thomson) largely replaced it, as it solved the two key limitations of the daguerreotype. Firstly, it produced a negative, allowing image reproduction and, secondly, removed the quality constraints of paper introduced by the Calotype. Photography, for the first time, had both quality and reproduction. Since then, the Daguerrotype has only seen special interest use.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass wasn't a photographer, but takes an auspicious place in American history. Born in 1818 to slavery, he was a staunch abolitionist, as well as an orator, writer, and politician. An intellectual, he wrote several books, speaking and campaigning extensively against slavery.

What is striking about Douglass is his progressive liberal ideology within a young nation, along with an acute ability to convey it. His views, perhaps surprisingly, remain contemporary. He believed in equality of all people, regardless of gender or ethnicity, while progressing this agenda by creating dialogue between different racial and political groups. He was criticized for entering into discussion to resolve differences and his response was a pragmatic one:

I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.

Douglass escaped the south in 1838, traveling to New York, where he essentially became free, a journey that took little more than 24 hours! He and his wife settled in Massachusetts, becoming a licensed preacher and beginning lifelong work as an abolitionist. In 1845, his first and best known autobiography, "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave," was published, selling over 11,000 copies in the first three years, going through nine reprints, and even being translated into Dutch and French. He spent two years traveling through Ireland and Great Britain, speaking extensively before returning to the US where he continued proactively supporting abolition, along with women's rights.

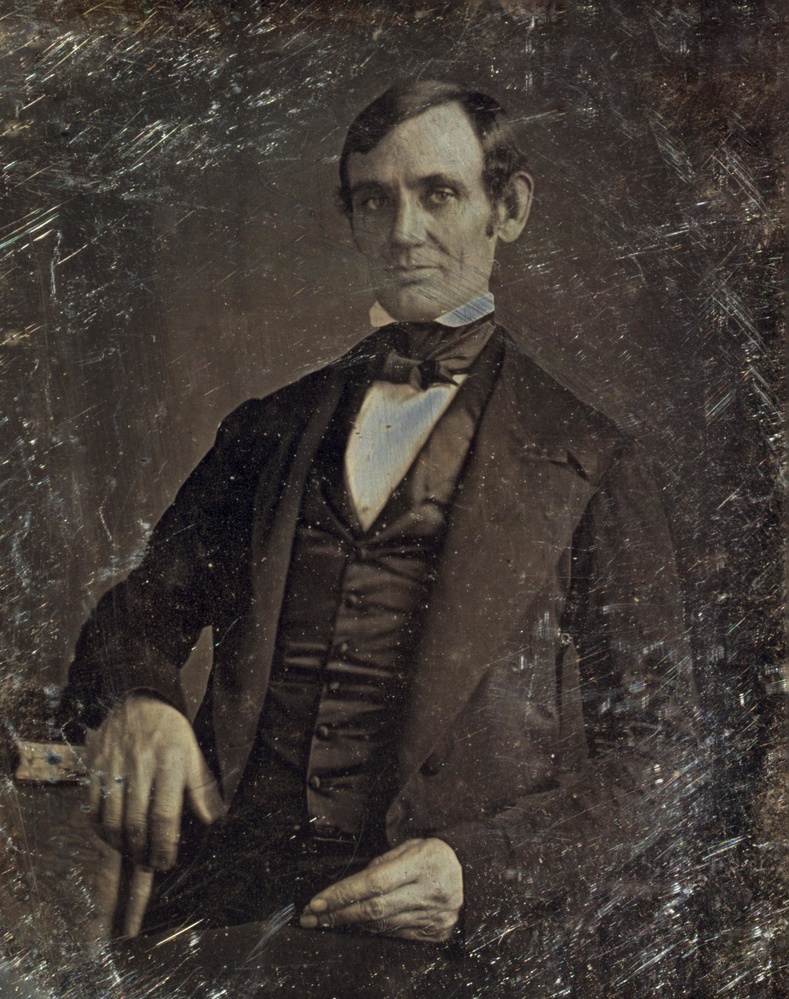

So what has any of this have to do with photography? Douglass is believed to be the most photographed American of the 1800s, even more so than his contemporary Abraham Lincoln. Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century's Most Photographed American presents many of these photos and outlines how and why Douglass was photographed. He saw utility in photography as a tool to support the abolitionist movement and in particular, the "truth value" of the camera to counter racist caricatures.

Douglass also published the first of several newspaper (the North Star) in 1847. Here then was an intellectual who used the power of mass media at a time when wood engravings were gaining extensive use to print graphics. Photography provided the linchpin in enabling graphically realistic imagery for mass reading.

Other Ds

Other Ds that didn't make the cut this week include the Decisive Moment, darkroom, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, DATAR, Bruce Davidson, Jack Delano, depth of field, documentary, Robert Doisneau, Terence Donovan, DPI, dry plate, and dye transfer.

A to Z Catchup

Alvarez-Bravo and Aperture, Bronica and Burtynsky, Central Park and Lewis Carroll

Lead image a composite courtesy of Skitterphoto and brenkee via Pixabay used under Creative Commons and Wikipedia, in the Public Domain. Body image courtesy Wikipedia, in the Public Domain.