Perhaps it was a technical mistake, gear breakdown, blocked access, or a moment of hesitation. We’ve all missed shots at some time or another. Here are mine along with my lessons learned. Tell me about you?

Reading Robert Bagg’s article on the images we might chase as photographers got me thinking about what shots I’ve missed. I’d love to hear your stories, find out what you’ve learned, and maybe see the shots that make up for those that got away.

Technical Mistakes

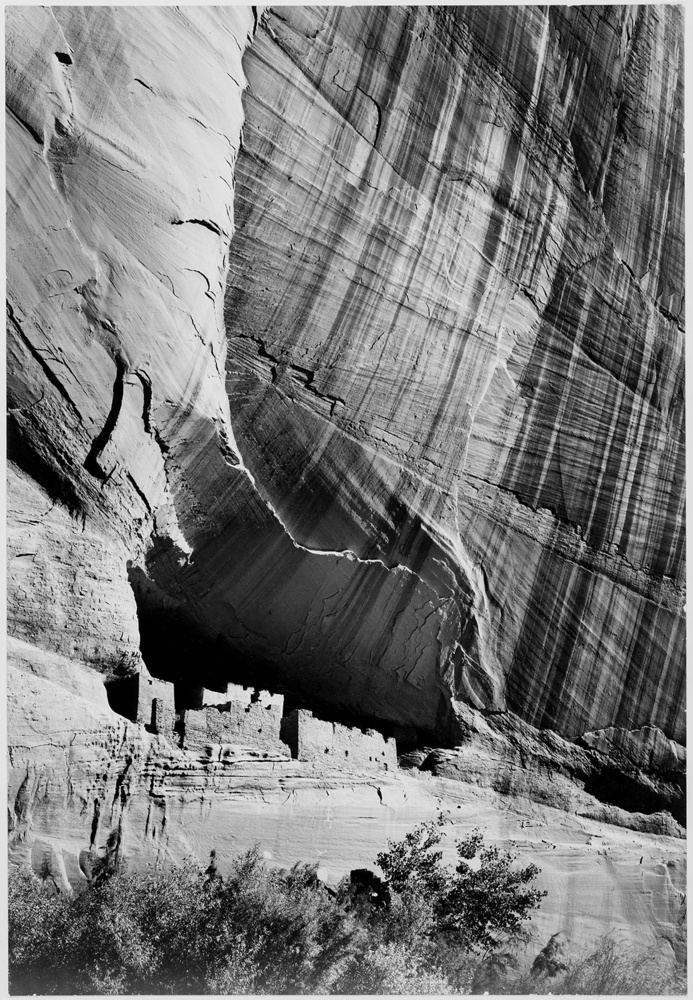

I wanted something like this. It was these Adams’ images from the U.S. Southwest of rocks darker than the sky that had me fascinated with how photography could do more than capture what the world looked like, that photography could be a representation of how I personally saw the world.

Ansel Adams - Canon de Chelly - National Archives, public domain.

By the time I got home a week later, the image was gone, lost somewhere in the downloading and card formatting cycle. I also lost my images of Monument Valley. Crushed.

Lesson learned: create a workflow for downloading and then erasing your media files from memory cards.

Sitting in a Jeep, watching a coalition of four brother cheetahs stalk some antelope across the short grass plains of Tanzania is one of my most cherished memories. I don't have a photograph, though. Basically, the cheetah was just too fast. As we prepared for the chase, I zeroed in on one particular cheetah. Focused. Set exposure. I was ready. When the cheetah broke for the antelope, I followed it through the viewfinder. It must have been running at about 60 or 70 kph. It was gaining on the antelope, and I was keeping up. I couldn't believe my luck. Then, of course, the antelope started to zig and zag, and the cheetah fell slightly behind. Seeing the antelope getting away, the cheetah changed directions and then changed gears. Closing in on 100 kph, I just couldn't keep up. The cheetah zipped out of my viewfinder. I struggled and failed to find the cheetah in the 400mm's narrow field of vision. By the time I realized I should scan for the cheetah outside the lens, it was over. The cheetah had tripped the antelope and was in the process of finishing it off. I had missed it.

Basically, my images go from this:

To this:

Cheetah hunt. let us go photo

Issues of Timing

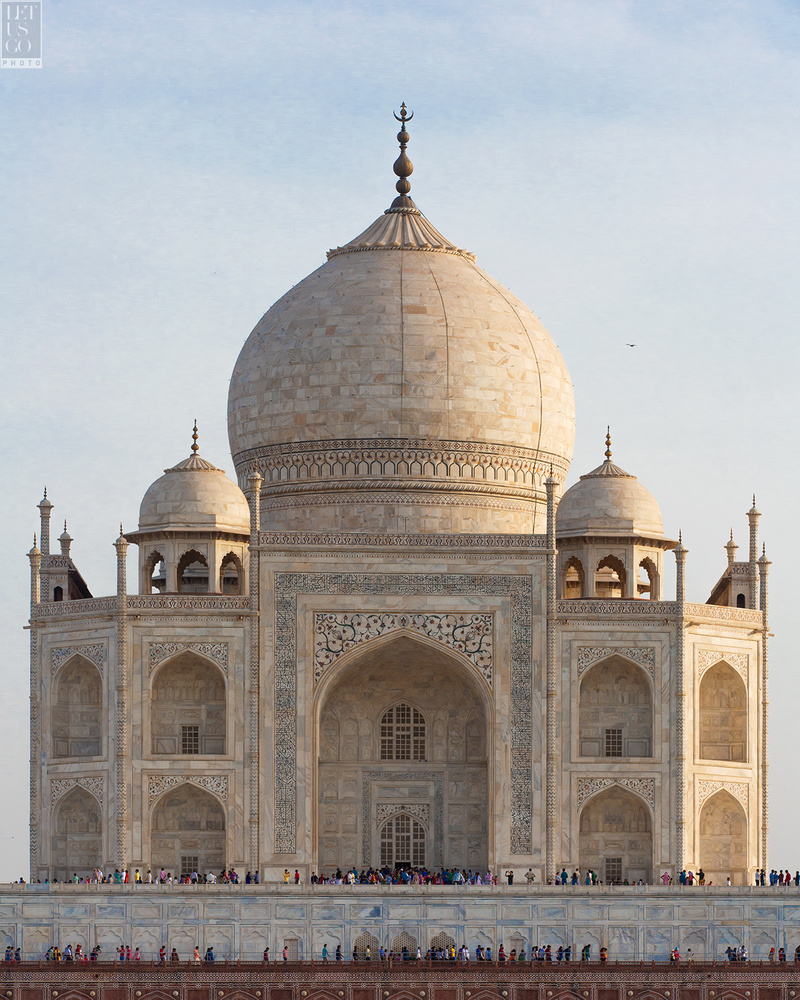

As part of my trip to Bhutan, I had a week-long stopover in India. With a bit of time to burn, I figured I’d make my way to Agra and see the Taj Mahal. Unfortunately for me, the four minarets surrounding the Taj were covered in scaffolding and the reflecting ponds were dry for maintenance. I had to be creative and went across the Yamuna River, cropping in tight to avoid the construction.

Lesson learned: sometimes, construction or maintenance will close off the angle you want. Take advantage of the situation and find a new way of looking at your subject.

The Taj from across the river, cropping out the minarets. let us go photo

Timing isn’t always related to construction or closures. Sometimes, you miss the rains in Africa by just a few days. I had planned a trip to Tanzania to see the migration, not the oft-photographed crossing of the Mara or Grumeti Rivers. I was after something different. The migration is mostly made up of wildebeests that are constantly traveling a giant circle around the Masa Mara/Serengeti ecosystem. The wildebeest are following the rain, which gives life to the vast grasslands. This ensures that there is enough food for their vast numbers, and, when it’s time, for the 80,000 calves born during an exceptionally short few weeks, the calving season.

Lots of wildebeest, not that many calves. let us go photo

Lions in love, with time to spare. let us go photo

Speaking of rain, I had always wanted to see Venice during the Aqua Alta — a city half-submerged. A ready set of reflections for the incredible Venetian architecture. To make this dream a reality, I planned to spend a few weeks in Venice during the mid-winter rainy season. Unfortunately for me, fortunately for the Venetians, the rain never came and I never did get my opportunity. I’ll tell you what, though, having Venice half-empty was a perfect trade-off.

Venice without the traffic. let us go photo

Blue bear. let us go photo

Red fox. let us go photo

Red fox versus arctic fox. let us go photo

Bad light at Tiger's Nest.

Tiger's Nest at sunset. let us go photo

Issues of Access

As a fan of Edward Burtynsky, while in Arizona I also made plans to get to the AMARG storage fields at Davis-Monthan AFB. I wanted to find a way to capture something like:

When I was there, it wasn’t possible to walk around on your own. The only way to see the “Boneyard” was to take a bus tour. So, my shots look more like:

Ya can't come in.

A little better. let us go photo

Issues of Earthquakes

Having traveled halfway around the world by plane and then spent an entire day bouncing along dusty roads to reach Bwindi, I could barely sleep with the excitement of tracking mountain gorillas the next day. Sometime in the middle of the night, the jungle came alive as the ground started to shake. The relatively minor earthquake only lasted about 15 seconds or so, but it was long enough that neither the jungle nor I were going back to sleep.

Still, excited beyond words, I bounded up with the sun, ready to hike. Normally, the mountain gorillas will travel a few hundred meters a day as they forage for food and then look for somewhere to bed down. Because of the earthquake, we later learned that the spooked gorillas had moved almost 11 kilometers. By the time we found them, we had been hiking for almost 12 hours, through Bwindi, the aptly named Impenetrable Forest. Far from my imagined idyllic moment with quiet and reserved gorillas, it was a running photoshoot. Low light, a lot of movement, and long lenses meant I ended up with almost nothing from the day. It was close to impossible to find the right angle or eliminate extraneous vines and trees as the gorillas bushwhacked through the jungle, resting only long enough to taunt me.

Hardest shoot ever.

I have one image from that day I still treasure:

Pensive. let us go photo

Thankfully, I had booked three more treks in various parks around Uganda and Rwanda. Spoiled, I was lucky to meet Guhonda, the largest silverback in the world:

Guhonda. let us go photo

Don't go to far little one. let us go photo

Newborn. let us go photo

All images provided by let us go photo, except embedded Burtynsky and Ansel Adams (public domain).