Time flies by. We’re already into February. Have you got your astrophotography planned out for the year? For astrophotographers, knowing what’s up in the sky and planning is the key to getting an interesting shot.

While it’s not impossible to do astrophotography by just popping your head out the door to check for a clear sky, it pays to know what is happening above your head ahead of time and not treat it like opportunistic street photography. Most astronomical phenomena are “scheduled” well in advance.

Observer’s Handbook

If you are a “generalist” with regards to astrophotography, a good way to plan ahead for the year is to get the annually published “Observer’s Handbook” by the non-profit Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC). This is a kind of “Farmer’s Almanac” for astronomers. Over the years (2022 marks the 114th), this book has expanded to over 350 pages of fine print.

Why do I first suggest this physical book? My reason is that it’s a highly condensed source for a wide variety of information of interest to astronomers. It brings together a great deal of information that is available on the internet but is scattered among websites belonging to many different organizations. At the very least it provides an annual overview and starting point for searching on the internet.

Since it is published by the RASC, it’s understandable that it is North America-centric, but all times are given in UTC (universal time). The heart of the handbook is the section “The Sky Month by Month” which provides a compact summary (2 pages per month) of significant sky phenomena, including:

- Lunar phases

- Conjunctions – close apparent approaches of planets and the Moon

- Eclipses of the Moon and Sun

- Meteor shower peak times

- Positions of planets in the sky

- Configuration of Jupiter’s moons, including highlighting of transits and shadow transits

In late 2020, Jupiter (visible with brightest 4 moons) and Saturn made a close approach in the sky over several days. The crescent Moon was added for scale. Nikon D850, 2x teleconverter, and 640 mm focal length Borg 100ED refractor was used. 1/125 to ½ second exposures @ ISO 400.

Additional pages include detailed discussions of the year’s sky motions:

- Timing and visibility of the year’s lunar and solar eclipses

- Jovian satellite positions (transits across Jupiter, behind Jupiter, moon shadow transits, etc.)

- Positions of the planets against the background stars

- Positions of the brightest asteroids

- Occultations of stars by the Moon and asteroids

- Brightness of planets over the year

Much of the publication also includes background information on orbital motion, astrophysics, optics, constellations, and deep sky objects and catalogs. Also discussed are weather-related topics such as the historical cloud cover over North America. Some of this background information is static, and for lack of room, highly condensed, but includes references to other books and websites, so it serves not only a good condensed review of useful information, but a good starting point for further reading. For newcomers to astronomy, these sections may seem intimidating, so a gentler starting point for general astronomy information is a book I reviewed earlier called “The Backyard Astronomer’s Guide.”

2022 Night Sky Almanac

A “lighter” version of a planning reference, also from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, is the “2022 Night Sky Almanac.” Unlike the thin, densely packed, black and white print pages of the “Observer’s Handbook,” the Night Sky Almanac is printed with glossy color pages on heavy stock. This year’s version contains 120 pages mainly organized as a month-by-month guide to the sky, including two charts of the northern sky per month. For astrophotographers, this book is a bit disappointing as it’s oriented more towards the beginning visual astronomer, but if you are actually just starting out in astronomy it’s a good reference to pick up at least once.

The almanac is aimed at northern hemisphere observers, and is in essence, the what’s-up-in-the-sky monthly center section of magazines such as Sky & Telescope or Astronomy, but with the advantage of getting the whole year right away and at a lower cost than a regular print magazine subscription.

On the other hand, a magazine subscription might be best for you if you like to read space and astronomy articles and don’t mind the short (a month ahead, typically) heads-up reminders of what will be up in the sky. And if you like to browse advertisements for astrophotography equipment, this is the way to go for you. For myself, I have to confess that although I subscribed for many years (decades) to astronomy magazines, I gave that up when magazines were squeezed by limited revenue and lowered printing costs by using cheaper paper and (smelly) ink.

Dynamic Events: Comets

For more dynamic events which might not be covered in the “Observer’s Handbook,” the internet is, of course, my preferred source of timely information. Objects such as comets are discovered and may become visible with little lead time. Or periodic comets (comets in closed orbits around the sun) which have sudden outbursts may not be covered in printed publications.

Feb.-March 2008 – Comet Holmes passes by the California Nebula. 3x20 minute exposures on medium format Kodak E200 (+2 push) with Borg 125EDF2.8 @ f/3.3.

Although you may not be aware of it, at any given time, perhaps a dozen comets are visible in amateur telescopes. Most of these are too dim to see visually, even at the closest approach to the sun, and generally lack a distinct tail when they are far from the sun, so they may not be appealing aesthetically, but determined comet enthusiasts regularly photograph these and post images at this online group:

https://groups.io/g/comet-images

Based on news and images posted in this group, you can use planetarium programs such as Stellarium to download the latest orbital data from the internet and see the comet’s position among the stars and nebulae for potentially attractive “combo” compositions.

The primary source for detailed information on all comets, see the comet page at the MPC (Minor Planet Center) at Harvard.

Solar Activity

Solar activity is another category of dynamic events which can only be approximately predicted in advance (i.e. increased chance of activity in years near the peak of the 11-year solar cycle). Sunspots can be seen on near-real-time shots from a network of solar telescopes and space probes or see the SOHO (Solar and Heliospheric Observatory) satellite site.

31 October 2015 -- Large train of sunspots march across the sun. Sunspots are visible for about 2 weeks due to the Sun's rotation.

Clouds, Smoke, and Eclipses

Even for astrophoto opportunities known well in advance (e.g. eclipses), our atmosphere may cause a problem, so here, the internet is a great boon for astrophotography. An example of this was the solar eclipse of 2017 which crossed the continental United States. From long-term cloud cover records, I decided that the best chances for a clear shot of the eclipse would be west of the Mississippi River. Based on that, several scouting road trips narrowed my choice down to the stretch from eastern Oregon to western Nebraska. My preferred choice would have been from my wife’s cousin’s location in Jackson, Wyoming, but smoke from forest fires drove me to move to eastern Wyoming in the last few days. To track the cloud and smoke cover on a daily basis, I used NASA’s MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) image site.

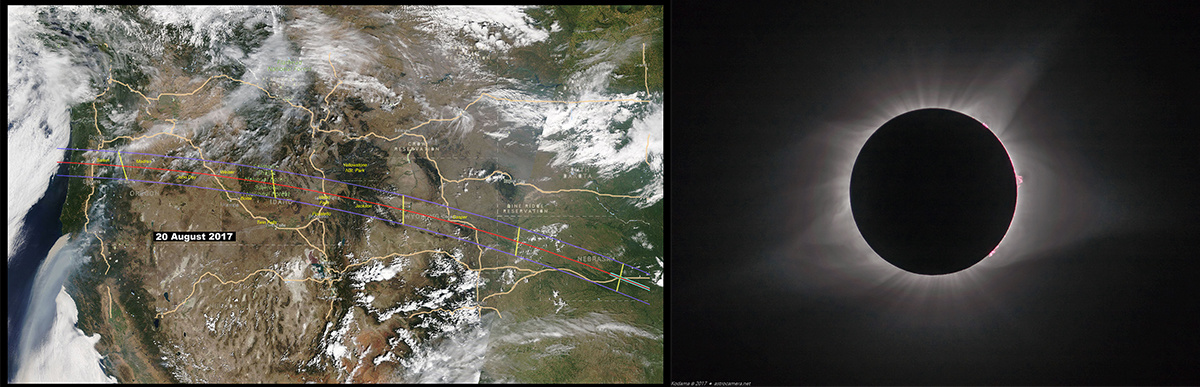

At left, clouds and smoke plumes over the western U.S. on 20 Aug. 2017.

At right, 21 Aug. 2017 – Total solar eclipse shot from Glendo, Wyoming. Nikon D600 @ ISO 100 + 1.4x teleconverter, Borg 100ED refractor (640 mm focal length).

For “normal” (48-72 hours ahead) weather monitoring at a specific location, a popular resource covering North America is the Clear Sky Chart. For a selected location, the charts show predicted cloud cover, temperature, humidity, transparency, wind, and even smoke.

Rocket Launches

Rocket launches aren’t strictly what we might categorize as “astro” photography, but if you’re near a launch site, these present a photographic challenge comparable to shooting an eclipse. To keep on top of these, an internet source is required. An Android app that I have found to be useful is Space Launch Now

Launches are subject to literally last-second changes, so it’s essential to keep as real-time a connection as possible (streaming broadcasts may be delayed 15 seconds or more) for status changes. SpaceLaunchNow does not itself provide the real-time status, but usually includes links to streamed webcasts.

In general, launches near sunset or sunrise when the rocket and contrail are illuminated by sunlight, but the sky and foreground darkening provide the best photo ops.

22 Dec. 2017 – SpaceX launch of Iridium 4 from Vandenberg AFB, California. At top left is the 2nd stage and payload heading for orbit. At lower right is the 1st stage reentry burn. Nikon D600 @ ISO 1600, 1/20 sec., Nikon 70-210 zoom @ 210mm, f/5.6

Aurora

Another dynamic sky event worth planning for is the appearance of the Northern Lights, which is generally tied to solar activity. Auroral activity is usually limited to rings around the Earth’s geomagnetic poles (northern latitudes are more accessible than southern). Since the solar activity is picking up at this time, it is a good time to start planning ahead for photoshoots.

December 2012 -- Aurora from Abisko, Sweden. Nikon D600 / ISO 1600 / Sigma 15mm f/2.8 / 15 sec.

Generally, late Fall, Winter, or early Spring is more favorable for chasing the aurora due to the longer nights, especially at high northern latitudes, but dramatic spikes in the intensity and dynamic movement occur when eruptions occur on the sun and auroral displays can be seen further south. So while a trip to the north can be planned based on general solar activity and weather prospects, catching the most dramatic aurora depends on monitoring “space weather” activity sites which can provide alerts as short as a half-hour ahead of an event.

Wide Open Skies

Whatever your astrophoto interests, the skies provide great opportunities if you plan ahead. The clock is ticking, and the sky is spinning by!