In the fall of 1962, the fifth American astronaut brought an iconic camera with him. It was custom built for the Mercury-Atlas 8 mission, and would ensure that Hasselblad was marked in history as the camera that photographed earth. Fifty-five years later, we may never see a camera quite like it. Famed Photographer Cole Rise has spent the last two years embarking on fixing that.

When America was beginning to send astronauts into orbit, getting a glimpse of that famous view wasn’t quite the highest priority. Nonetheless, creating a custom engineered Hasselblad 500C was one of the most recognized engineering marvels surrounding NASA’s race against the Soviet Union.

“This is camera has been an obsession,” he explained to me. “I spent the last two years building out a metal workshop, cutting my teeth on a mill and a lathe, and becoming a Hasselblad technician to get my head around everything NASA needed to know to make this camera a reality.”

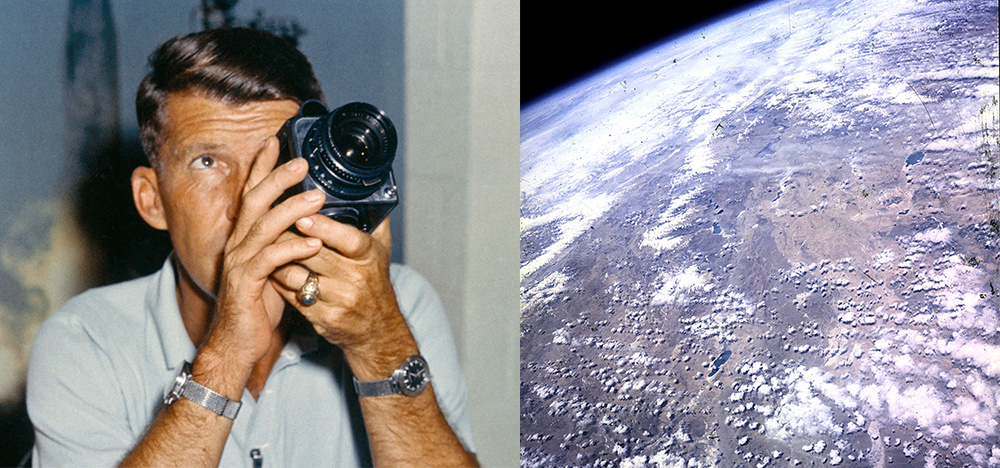

Toying with the original concepts (left); the famous image taken with the camera and an 80mm f/2.8 lens (right).

For anybody who isn’t familiar with Rise’s work, feel free to check out a previous article we wrote detailing his photographic kinship with space exploration. He’s notably the brains behind the Instagram logo, as well as a collection of their filters. I’m sure that ought to dispel any speculation as to his ability to undertake this project, and understanding exactly what makes a Hasselblad tick. He also occasionally shoots with a Hasselblad 500 C/M from the 80s.

Apparently it takes two or three weeks to modify an original 500C. Rise refurbishes all of the critical parts, on top of recreating NASA’s exact methodology for customizing the camera. Finding the cameras has proved difficult, as most suppliers only have the 500 C/M model (M standing for modified by the factory for an automatic back). This is an extremely limited run, with only ten cameras expected to be made.

Shaving every ounce of weight they could.

The History

Astronaut Wally Schirra used the 500C on his earth orbiting Mercury Atlas mission. Previously John Glenn had shot 35mm, which didn’t produce the clear results that were preferable. Apparently Schirra consulted with a collection of photographers for major publications, and landed on using a Hasselblad instead. Not only did it have a larger film plane, it was reliable and donned an interchangeable film back even while mid-roll. He had bought it in a local camera store and that’s when the NASA modifications began.

Photography was becoming more and more important in space-flight. By experimenting with photography, NASA was contributing to our understanding of how a spy or weather satellite might work. There’s also something to be said for distributing these photographs to the public and arousing interest in further exploration.

Before and after – the original modifications.

The NASA Modifications

When an astronaut takes a camera to the ISS today, they would only have a couple modifications to better suit astrophotography. Chris Hadfield was able to being a Nikon DSLR and a 400mm lens up in 2013, and the ISS is equipped with super-wides all the way up to an 800mm lens. In 1962, photography was a new challenge on long list of issues. There was a lot needed to ensure the best shot was taken and that it didn’t get in the way of the work being done.

Anti-reflective Paint

Let’s start off simple: reflections. What good is a photo if you can see the camera reflecting in the window? The original camera was painted a matte black to avoid this very problem.

Custom Viewfinder

“The window was located behind the astronaut, just above his head, so it was impossible to frame a shot with a waist-level viewfinder,” Rise described. So it makes sense that NASA removed the guts of the viewfinder (mirror/focusing screen) and covered it up with an aluminum plate. They replaced it with a simplified optical viewfinder on the side, that meant you could see and shoot with a space helmet on.

Modified Film Back

If you’re careering through space, with huge gloves on, you might not be trusted to handle the intricacies of a Hasselblad film back. Luckily, NASA carefully removed the film latch and replaced this with two holes for a spanner wrench. This way, it could only be opened up when the camera returned to earth. The back was expanded, to hold 100 frame rolls instead of the usual 12.

The workshop in which Cole Rise has been modifying the cameras.

Slimming Down

As he pointed out, “a water bottle cost $10,000 to launch on the Space Shuttle.” If weight is that expensive now, I can’t imagine was cheaper in the 60s. As such excess material was drilled from the wind crank, and film back. It also helped that they’d already removed the focusing screen and mirror.

Space-Aged Velcro

Much to my dismay, Rise debunked the myth that hook-and-loop Velcro was created for space. According to him, “the Velcro corporation did produce a special variant of the material, however, for exclusive use aboard NASA missions, which quickly popularized the brand.” It’s still not available to the public — apparently he tried to get some for this project.

So it makes sense that we might associate Velcro with space exploration. The modified 500C was fixed with Velcro to stick to the wall of the ship. Luckily, the Mercury Program used a more common version of Velcro that is still available today. I trust that Rise has nailed this: “I’ve even counted rows of hooks to exactly match the original camera.”

The black model stays true to the original, whereas the chrome version retains certain bells and whistles.

Getting One

The real thing sold for $281,250 at auction, which is a little too high for most. If you’re not willing to drop that kind of money, Rise is selling the chrome version for $4,200 and the anti-reflective black model for $4,800, with 10 percent going to Charity Water. A regular 500C goes for about a thousand bucks on eBay, but that’s hardly a competitor to this project (when it might not even work too).

I’m duly envious of whoever receives these. Not only are they stunning (personally I prefer the “Space Chrome”) but they’re functional as they were in space. That’s just nuts! Of course, if you want, you can have the 12-frame gear system, variable focus in the lens, and film latch left intact for everyday shooting.

Matching cases for the cameras are a nice touch.

Rise is packaging them with a matching Pelican case, a vintage 80mm f/2.8 Hasselblad lens, a cold-shoe for mounting a viewfinder, a spanner wrench for accessing the film, and a “Bonus Space Artifact” which is even a mystery to me.

If the price sounds too steep, or you were the person to buy the original for a quarter-million dollars, then you can pick up a print of the Mercury Space Capsule instead. What comes next? After this limited run, Rise is looking into creating Apollo replicas which he hopes to have available in 2019. According to him, these will be far more complex. I can only hope I've got a couple thousand bucks lying around when the next set come around.

Images used with the permission of Cole Rise. NASA archive images are under a Creative Commons license.

[via Cole Rise]

Neat! I was; however, waiting for the explanation of why he had to do this in space.