In the early hours of Friday morning U.K. time, Magnum took its entire archive offline. Later that day, it released a statement explaining that it was reviewing its practices following revelations about some of its photographs. Difficult questions still need to be answered and the sequence of events shows how, despite Magnum’s crisis management, they’re not going away.

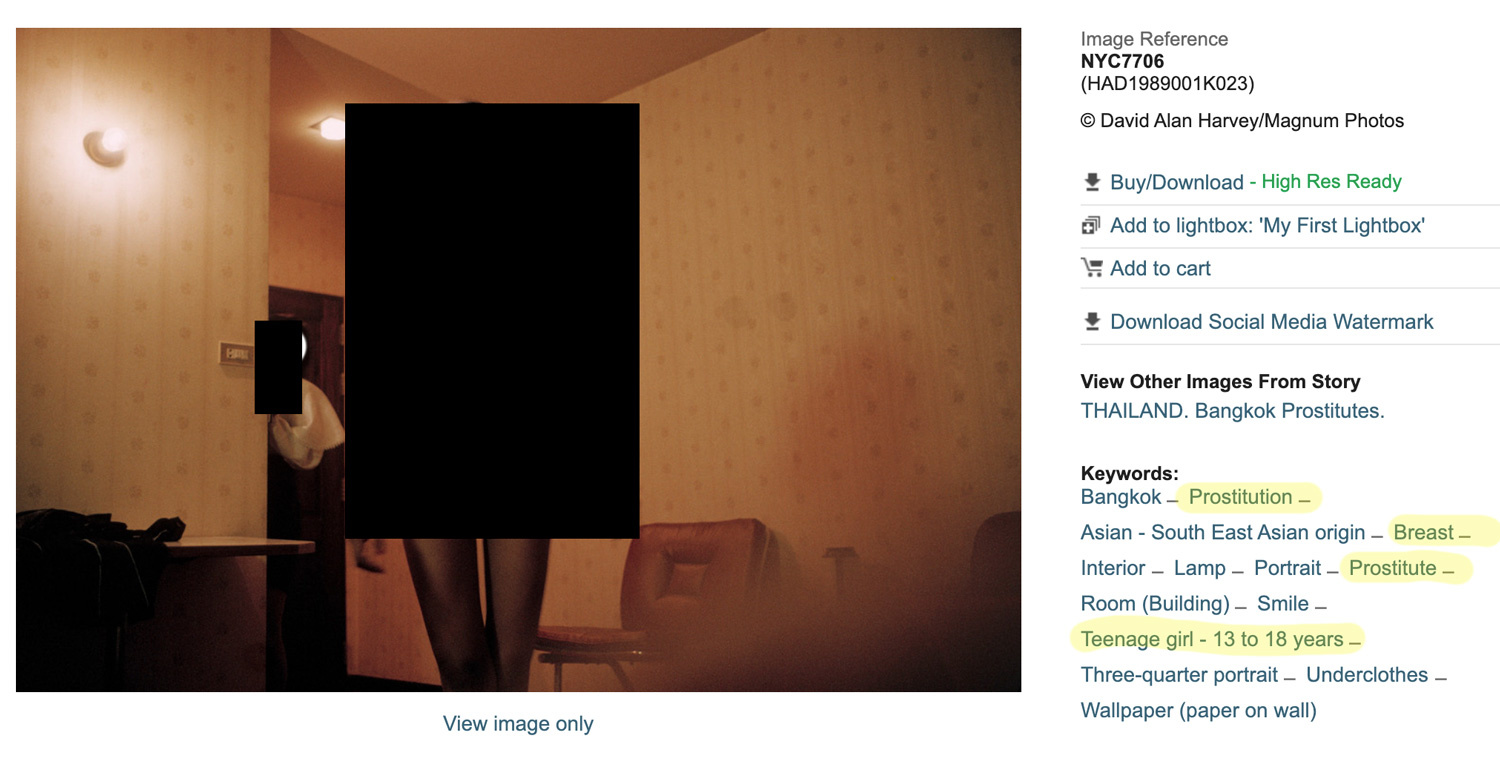

On August 6, Fstoppers broke the story that Magnum had been selling sexually explicit images of what appear to be children, potentially for more than 30 years. A longer article followed up the discoveries, and the photographs by David Alan Harvey were quickly taken offline without any announcement, but a large number of images of sex workers remained available for purchase from the agency’s archive.

Putting aside the question of why photographer David Alan Harvey was being approached by what appears to be a naked child in a dimly lit room, shooting from a low position while another, older woman smiles from around the corner of the door, Magnum’s keywording was proving to be a problem. As discussed by Allen Murabayashi in the Vision Slightly Blurred podcast, it’s not unusual for agencies to outsource the processing of vast swathes of images in its archives as adding keywords is a laborious process. The unfortunate keywording of the images produced by Harvey during his time spent in a Bangkok brothel could in part be attributed to a process that is not particularly sophisticated.

Other images, however, suggest that the issue is more complex. In 1985, Magnum photographer Miguel Rio Branco published his photobook Dulce Sudor Amargo, a study of life in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, a city widely known for its sex tourism. According to the Magnum website, “the photographer’s fascination for these places of strong contrast essentially resides in the power of the tropical colors and light, which he conveys by means of his pictorial sensibility.”

This pictorial sensibility included a photograph that features the caption “Prostitute lays on wooden floor.” Branco shot the image as he stood over the identifiable woman as she lay in front of him with her legs open. One of the keywords for the image in Magnum’s archive is “vulva.”

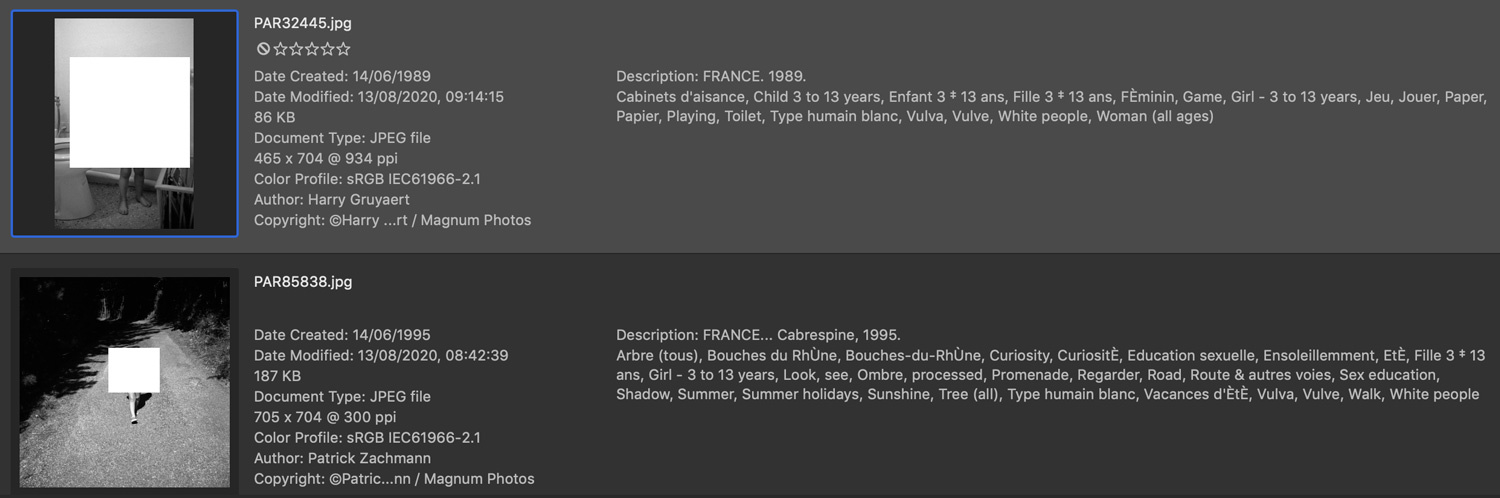

It’s not clear why would anyone wish to search the Magnum archive for images tagged “vulva.” Among the search results were two photographs of girls who appear to be younger than five years old, both naked from the waist down and with their genitals visible, seemingly family photographs by Harry Gruyaert and Patrick Zachmann. One is also tagged “sex education.” To be clear: there is nothing indecent about these images, and there is nothing ethically problematic about them as family photos, assuming that they are the children of the two photographers who produced the photographs. However, it is alarming that they are available to download from the archive of a global photo agency and tagged so that visitors to the website can easily find them by searching for images of children’s genitals. Magnum has these images in its library; it must be able to explain how they were produced and why they were made available for licensing.

Keywords Removed, Problems Remain

Following questions on Twitter about the Branco image, Magnum removed the visibility of its keywords from its archive. However, while the keywords were no longer listed alongside a photograph, they still appeared in the metadata of the low-res images that Magnum served for those browsing the website.

Magnum was then challenged as to why a photograph by Alec Soth of a young cheerleader — “13 to 18 years old” — was tagged with the word “vagina.” A day later — and almost a week after the David Alan Harvey images were revealed as potential child sexual abuse — Magnum took its entire archive offline for a “scheduled upgrade.” Late on Friday afternoon — a time often used by governments and corporations to bury bad news — Magnum issued a statement.

The Statement

Olivia Arthur, president of Magnum Photos, issued a statement on the Magnum website. It includes the following:

Recently, we have also been alerted to historical material in our archive that is problematic in terms of imagery, captioning or keywording and we are taking this extremely seriously. We have begun a process of in-depth internal review – with outside guidance – to make sure that we fully understand the implications of the work in the archive, both in terms of imagery and context.

Arthur notes that in the 75 years that Magnum has been photographing the world, “standards for what has been acceptable have evolved. Issues and questions that were previously overlooked have to be addressed.”

Magnum has called in a crisis management consultancy to help it navigate its current challenges. “Our experts make crisis incidents disappear,” the consultancy's website claims. “We … manage the crisis so that the outside world remains unaware there ever was an issue or, at the very least, ensure the negative impact is much less than you originally feared.” It can likely be assumed that these lawyers have drawn up a strategy which is now being mulled over by Magnum’s members — the ultimate decision-makers — some of whom will almost certainly be enraged by the measures being proposed.

The statement from Magnum’s president, though thoughtful and well-worded, is hard to reconcile with the agency’s record. In 2017, the agency’s Global Business Development Manager, responding to concerns that Magnum and LensCulture used a photo of an alleged child being raped to promote a competition, stated that “the protection of vulnerable and abused children is of paramount importance to Magnum Photos.” Given that scores of images of child sex slaves — many of whom were identifiable — remained in the archive for another three years, this was patently untrue.

The Deafening Silence

Unlike most other photographic agencies, Magnum is owned and run by its members — the legendary photographers whose incredible images have been revered by the industry for decades. This elevated status seems to have bred a culture of arrogance, fed by a sense of untouchability established by their connections and clout. Photoland remained almost silent during the week following revelations about David Alan Harvey’s sexually explicit images of what appears to be a child. Magnum’s photographers are not just photographers: they are writers, editors, curators, consultants, and more. They are career-makers. As a result, photo land is still largely terrified by the prospect of discussing Magnum’s ongoing problems because too many individuals can’t speak out for fear of upsetting photography’s elite gatekeepers. Elsewhere, major publications such as the New York Times remain silent as even mentioning the scandal would undermine long-standing friendships built on years of mutual backscratching.

As discussed in the article that revealed David Alan Harvey’s troubling photographs, the culture within this tightly knit agency of photographers is frequently void of moral considerations. “I have no ethics,” says Bruce Gilden proudly, clearly gleeful in how his photographs treat their subjects like trophies, an attitude that the art world — dominated by Magnum’s chums — has rewarded over and over. Magnum’s former president described sex workers covertly photographed as “models,” and the agency recently used an image of an alleged child being raped to promote a competition. Martin Parr stood down from his role as director of the Bristol Photo Festival last month after being listed as the editor of a republished photobook from the 1960s that juxtaposed a black woman with a caged gorilla. Whether the photographer was making a racist commentary or not is now almost irrelevant: Parr was made aware of concerns about racism in May 2019, didn't respond until December, and chose to continue promoting the book for more than a year.

Images of Suffering

Magnum has produced some truly remarkable and hugely influential photographs over the years, but for many — especially in light of the questionable decisions and assertions listed above — the signs that it has a cultural problem that goes to the core of its organization is not a revelation. John Edwin Mason, teacher of African history and the history of photography at the University of Virginia, was called upon by National Geographic to review its archive in 2018. In a series of tweets last week, Mason explained how Magnum developed its culture of ends (i.e., art) always justifying the means (e.g., exploiting the plight of sexually exploited children). “After founding Magnum, right after WWII,” Mason explains, “they built its reputation by photographing the world. They especially traveled pathways that British and French imperialism had created and that was increasingly maintained by the US. Imperialism & white supremacy gave them the ‘right’ to go.” He continues:

Imperialism and white supremacy also granted them 'permission' to photograph virtually any black and brown person, no matter what circumstances they might be in and over whatever objections they might have. To a large extent, Magnum’s reputation came to rest on its images of suffering or exoticized black and brown people. People who didn’t have the power to say no. People who had no ‘right’ to photograph the places Magnum’s photographers came from. But, you say, Magnum’s photographers were the good guys. Humanists. The very model of the ‘concerned photographer.’ That’s true of many of them. But they were trapped in systems larger than themselves. They failed to recognize that. And they never put their own house in order.

Magnum is now scrambling to do just that. (Note that Mason’s use of the term “white supremacy” refers here to colonialist attitudes of entitlement, not to far-right hate groups.)

The statement from Arthur falls short. It talks of a journey, problems that must be solved, a realization that attitudes have evolved, and a will to understand. There is, however, no apology, no contrition, and no mention of the sexually explicit images of what appear to be children produced by David Alan Harvey. It says that it recognizes that there are issues, but very carefully it does not mention what those issues are.

A Right to Report?

Some commentators are keen to invoke conversations about freedom of expression, but all of that can be put aside for one simple reason: creating indecent images of children is an offense. A first-time offender in the U.S. faces a statutory minimum sentence of 15 years in prison. Journalistic intent does not even begin to figure as mitigation and claiming a duty or a right to report will not be considered a defense. After this article appeared, Conde Nast may want to consider reminding the editors of Wired Italia, one of its subsidiaries, of both the law but more importantly, the company’s Code of Ethics, not to mention its Code of Conduct, notably a document that was hastily drawn up after sexual harassment allegations were leveled against Mario Testino and Bruce Weber.

In short, photojournalism simply cannot give sex offenders a means of gaining access to vulnerable children.

Questions Remain Unanswered

As it stands, the questions listed in a previous article remain largely unanswered:

- Why was Magnum photographer David Alan Harvey taking sexually explicit images of what appear to be children in Thailand in 1989?

- Does Magnum acknowledge that creating a sexually explicit image of a child constitutes an act of child sexual abuse?

- Why does Harvey have a photograph of what appears to be a naked child approaching him where he is sitting or lying?

- Why did Harvey think it appropriate to submit this image to Magnum’s archive?

- Why did Magnum think it appropriate to include Harvey’s images in its archive?

- Has Harvey been suspended from Magnum?

- Will Harvey be subject to an investigation?

- Will Magnum report Harvey’s images to the police?

- Will Magnum ensure that any images of child sexual abuse in its archive are destroyed?

- Will Magnum accept an investigation of its archive with the oversight of a child protection officer?

- Why did Magnum fail to review its archive properly following an outcry in 2017 over its use of an image of possible child rape to promote competition?

- Is Magnum finally willing to remove hundreds of images of child sex slaves from its archive?

Get In Touch

If you have information about the conduct of a photographer or an organization and wish to discuss it in confidence, you can email photoland.confidential@protonmail.com.

Andy is trying to make a difference, in spite of the constant criticism. So many of the commenters spend more time criticizing Andy, and his work, than talking about the issue of child exploitation.

Self-promotion? I didn't see Andy promoting his website, or crowing about how he is such a caring person, noble in his quest for justice for children. He recounts his personal fight to right a terrible wrong. This is wrong? How have you contributed to the fight against this crime?

I am appalled. This is a topic that needs exposing. So many commenters refuse to acknowledge the wrong in the abuse of children, and put the onus on others to end the problem. "It was a different time". Different societies have different laws. At the same time, they sound like apologists for the very abuse they claim to condemn, when pushed by other comments.

It is a sad world that tolerates the abuse of children. Is this such a difficult or contentious issue?

It is always wrong to judge people by actual ethics or morals. Sure there will be the ones that favour hiding any expression if it doesn't fit into their present politically correct standards. But if we do this we risk to loose all of our culture from before the Greeks until 10 years ago. Someone has said that at some point in the future eating animals farming them to slaughter will be looked as a form of creature genocide. Will all images, films, movies, etc we taken out of sight. Will all the ones that created them be put on a cross so everyone can throw stones at them.

And it is always baffling that people get so upset about some genitals but they accepts if you have people being assassinated, tortured, labour exploited etc. Same goes on with films. You see a naked butt it's for 18, but a film with tons of violence does not get the same restriction treatment.

Magnum and so many great agencies and photographers have documented war, violence, etc but we pick up to condemn a few that have chosen to photograph a naked child in a documentary context. Weird prude society if you ask me and more weird all those individual that carry the torches to burn down every building or person that does not conform to their moral point of view of the world.

_