Jonathon Keats is an American conceptual artist based in San Francisco. This year Jonathon began a new project he calls Century Camera in which he (and the people of Berlin) hide 100 pinhole cameras with the hopes of creating the first series of century-long exposures. Jonathon was kind enough to make time to speak with me and share the details, inspiration, and process behind this ambitious project — you don't want to miss this.

Jonathon describes himself as an experimental philosopher. In college at Amherst, he studied philosophy but found the discourse to be lacking what he was hoping to get out of it. "I found that the philosophy that I was studying didn't really satisfy what I had hoped I it would; kind of a broad-base-curiocity about the world that I had. But [rather than turning into] a broader conversation, I found it to be highly technical, the people participating in it to be too few and far too narrowly-focused. It was too restricted."

Not finding what he was looking for in his studies of philosophy, Jonathon's focus shifted to the arts. "I guess I rebelled. I went into the arts as a way to do philosophy in the way that I thought we ought to, in a way that I wanted to do it. Essentially, to take thought experiments out in the world where a proposition is put out there and it's totally open-ended. It's an experiment, literally in which everyone interacts through which we can explore ideas about ourselves and ideas about our society. Everything that I do is motivated by that in one way or another."

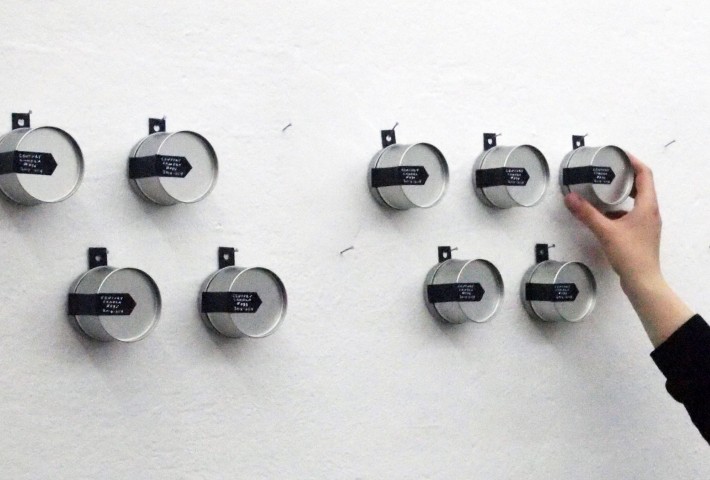

Century Camera pinhole cameras displayed at the Team Titanic gallery, Berlin.

Century Camera pinhole cameras displayed at the Team Titanic gallery, Berlin.Keats' work has covered many different topics, media, and have taken place around the world. The Century Camera project wasn't Jonathon's first venture into the world of photography, but it definitely is his most ambitious. Jonathon explains, "I'm not a photographer by any means, though I've studied enough to get myself in trouble. My interest in photography is my current fascination of trying to think and look in the long-term, not really in an interest in developing photography as a medium."

Jonathon's experimentation with photography came as a result of bathtub-based cyanotpye. "I'm very interested in some of the earliest types of photography, particularly because there's the possibility of doing everything yourself. I could buy a few chemicals and, using my bathtub, effectively replicate the entire process and experiment with it much more freely than I could, for instance, making use of contemporary color photography where I just don't have the knowledge, resources, or ability to work with the chemistry required."

A result of using this nineteenth-century process is the immense length of time required to properly expose an image. Jonathon continued, "I took the earliest chemistry for cyanotype, which is, as you know, unbelievably, agonizingly slow. It is so incredibly light-insensitive. I made my own paper, and decided to put it in the back of my Nikon F and leave the shutter open for a few minutes — didn't work, a few hours — not much better. I ended up exposing the better part of the day in order to get a 35mm image. Then I started to experiment with a slightly larger format with some old Brownie Hawkeye cameras that I owned. I found that I was getting up into the range of one week for an exposure. These pictures in their own right never became a project or an artwork but they got me thinking about photography over long spans of time and what it meant to take a photograph."

This experience with week-long exposures inspired Jonathon. He reflected, "Time itself becomes if not the primary subject at least an essential part of the image in which all that transpires is compacted. In effect you have a movie that is all in one frame. The entire span of time is there to be taken apart and interpreted. [A seven day exposure] was interesting but not really enough to get into some of the real potential, some of the real truths that might come up if it were to be really expansive. For me, really expansive is longer than a human lifetime."

For Jonathon, the next logical step was an exposure so long it could document the entirety of a human lifetime. "The interest in making a photo of that length came out of another area, another subject that interests me; how difficult it is for me to be aware of the changes that involve me and my surroundings on a day-to-day basis. In cities like San Fransisco, where I live, these changes can be very extreme, and noticeable when I've been away for a month. But day-to-day these changes are invisible to me and any changes that were initially noticeable are slowly assimilated to me."

"I was thinking about how I may see from a perspective, psychologically at least, that would take me far into the future so that I might look over a long span of time. So, conceptually speaking, that was what motivated me to make these cameras; they became time capsules in a way. [They're entities] you're aware of, but belong to a future date such that you look at your surroundings from that future, indeterminate point with a different point of view rather than that of simply getting on with life where everything is happening in the moment."

Century Camera owners examining a map of Berlin, choosing a location.

Century Camera owners examining a map of Berlin, choosing a location.The process employed in this project is unique and rather surprising, Jonathon explains that his father, a print dealer, was always concerned about sunlight entering his storefront, knowing that it would fade the pictures he was selling. It was an adaptation of this process that would enable Jonathon to use a simpler process than traditional photographic film for his exposures. "That's been imprinted for my entire life, I never realized how much so but somehow when I started thinking about how I could extend the length of a photograph, it occurred to me that what had terrified [my father] about sunlight degrading his prints might be a process I could use to make an image. I could take a piece of black paper, use it as my "film", and by fading slowly, a focused beam of light, I'd end up with a positive print."

"Using a pinhole camera as a way to do it would ensure the level of light reaching the paper was incredibly low and allow me to do so in multiple. A pinhole camera is so simple and inexpensive to make that I could make many of them. Of course there's a lot that could go wrong. There's a lot that will go wrong. If one of these pictures out of the 100 cameras is to come out I'd be very surprised" Jonathon pauses, laughing to himself, "Of course I'll be dead but that's another matter."

"I think that any complication, any complexity that can be removed increases the chance that it will result in an image. Eliminating the lens, making it so it's something that is incredibly simple and also something that's incredibly intuitive. Somebody 100 years from now doesn't need to know anything about this project in order to find and interpret the image to me that was the way to go about a project that would involve such long span of time."

Rather than personally hiding the 100 cameras around Berlin, he decided to democratize the project. Anyone in Berlin was welcome to stop by the gallery which sold the cameras (with a deposit to encourage their safe return in 100 years). "Making 100 of these cameras, and giving them to people was a way to have people involved in the process of putting them out in the world. This is a totally unauthorized action that is undertaken by the people of Berlin and other cities as well in the future. They'll go and put these cameras out in the world and make a number of tough decisions. First of all, what might serve as a platform that might last for 100 years, that might be well enough hidden so that it won't be found over that 100 year period. But more difficult, more challenging as a question is what is worth looking at over that 100 years? What will change, and what will change in a way that is truly significant? The cameras are very much about the process, of long-term thinking."

A Century Camera pinhole camera hidden in Berlin.

A Century Camera pinhole camera hidden in Berlin.Jonathon has high hopes for the project in the future including lengthening the time period of the exposure and broadening the subjects photographed through the proliferation and distribution of the cameras to more and more people. "100 cameras, 100 people isn't really democratic. There are many, many more people in Berlin let alone the world. I decided upon 100 cameras initially because of the nice symmetry, 100 cameras for 100 years but also that's really what I can afford to do at this moment. But ultimately I believe the project could involve a camera for everybody. The best, the most interesting way to undertake this project would be under the auspices of Unesco or some other organization, where everyone as a birthright is given a camera which they hide away as a child. In 100 years, it would be retrieved so that what happens is this continuity through time. After 100 years every day there could be a new exhibition while at the same time every day new cameras are going out into the world. That way we'd outlive ourselves in terms of our concerns, our responsibilities. There's a sense in which biologically it extends us to become responsible to the level of the effect that we inevitably have on the world."

"I think that a 1,000 year version is something that interests me, I'm already looking into that, potentially in New England, but generally out in nature. Obviously this would require a new substrate, and perhaps some changes in the technical process to make this work."

Jonathon's ultimate goal is that others would take up this project, experiment with and refine the method of taking ultra-long exposures in order to document the passing of time on this immense scale with him. "I hope that people reading this article will be encouraged to take this up, to make it better than I could, to bring it to their cities."

A sample exposure from the Century Camera setup.

A sample exposure from the Century Camera setup.To keep up with Jonathon and his work be sure to check out his Twitter, or his representative galleries:

Team Titanic Gallery, Berlin | Modernism Gallery, USA

I don't know why, but I fear projects that last longer then a human life.