Printing is hard. Rather, printing well is hard. It's been a little bit science. It's been a little bit art. Trying to make digital prints look like traditional darkroom prints is even harder still. But is it possible?

While I was writing my last article about Hahnemühle's's new natural papers, I had the chance to talk with both Travis Mc Connaghy at Hahnemühle and Tom Underiner, a master printer at Pixel River.

Where Mc Connaghy is driven to create and optimize the tools used by printers, a science, if you will, Underiner's intention was to take those tools and find a way to bring the magic of optical printing to digital. To use a simile, if Mc Connaghy is an obsessed scientist striving for a perfect profile, Underiner is a cross between a magician and a monk, intent on finding the otherworldly aspects of turning light into printed paper and ink.

Travis Mc Connaghy at Hahnemühle

Paper / Printer Profiles

Although Mc Connaghy has several different roles at Hahnemühle, one of his core responsibilities is creating profiles for their paper.

A perfect profile would allow most of the people in the world to get the same print using the same inputs.

Mc Connaghy uses Chromix's Colour Think to evaluate the profiles that are made available to printers and photographers using Hahnemühle's products. Mc Connaghy explained that the real trouble arises because monitors have a luminance to them, whereas most print media doesn't. There is, therefore, quite a bit of work that goes into creating a profile that will ensure the printer can create a print that looks like the image on the monitor.

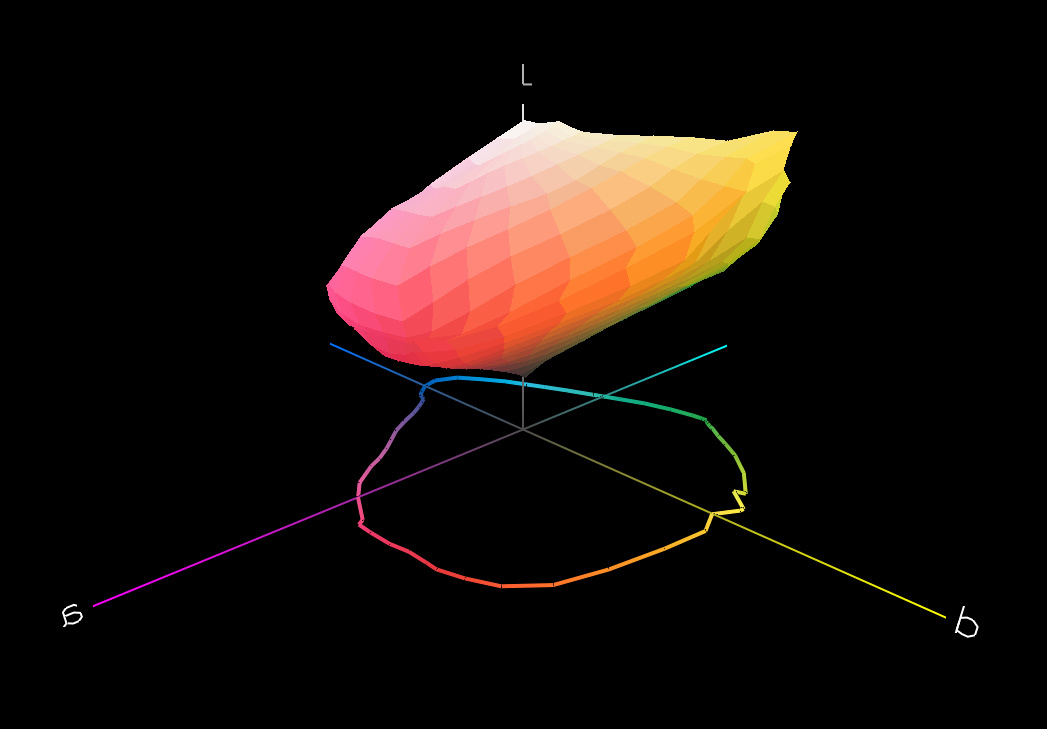

Mc Connaghy works with dozens of different printers, creating 3D maps of his profiles to look for outliers. You can see the differences between a good profile and a flawed profile below.

In the flawed profile, you can see how jagged the 3D model is, illustrating that there are several outliers that would result in the monitor, printer, and ink not working well with the paper. A profile like this would mean that the printer, ink, and paper wouldn't be able to replicate the color spectrum seen on the monitor. The print would likely be muddy, dull, and exhibit unintended color casts.

An example of a flawed profile.

In a successful profile, you can see how smooth the 3D model is. This would provide for smoother gradients and print instructions that allow the printer and paper to meet the expectations shown on the user's monitor. This profile would allow for smooth color and density changes as well as excellent color fidelity to the monitor.

An example of one of Hahnemüle's successful profiles.

When the flawed profile (in green) is superimposed on the successful profile, you can see how small and jagged the flawed profile is. It simply wouldn't allow the computer to transmit the proper color information to the printer in order to instruct the printer to work well with the paper.

A comparison of a successful and a flawed profile.

In managing these profiles, Mc Connaghy will often hear from photographers and printers that are experiencing problems or quirks. For example, differences in relative humidity, HVAC temperatures and pressures, and even altitude may mean that a profile has to be tweaked.

Hahnemühle's's Certified Studio Program

If you're looking to have your images printed by a professional, Mc Connaghy suggests looking for a Hahnemühle Certified Studio. The Certified Studio Program was launched about 5-7 years ago. To be certified by Hahnemühle, a studio has to prove its accuracy at consistently high standards. For those who are showing away from home and don't want to ship framed work, this is a solution that will guarantee you results.

Favorite Papers

As with each of the interviews in this series, I asked Mc Connaghy what his favorite paper is. Mc Connaghy's favorite paper is Hahnemühle's William Turner.

Hahnemühle's William Turner.

No other paper in the world like the William Turner.

Mc Connaghy explained that the William Tuner is made using a mould-made machine. This is apparently about as close to handmade as you can get without being handmade, of course. I've been told that there are only a handful of mould-made machines left in the world and that only a few of these are used in the fine-art printing industry. A mould-made machine lays down the fibers in each roll in a unique pattern. This means that although Mc Connaghy and his team have made an effective profile for this paper, no two prints will ever be identical. Their color and density fidelity will be the same, but they will always have subtly different textures.

Tom Underiner at Pixel River

Underiner is a master printer at Pixel River in Pittsburgh. Over the years, he has helped some of the best photographers turn their visions into a finished product. Underiner comes from an optical printing and traditional darkroom background. Having cut his teeth printing from negatives, Underiner sees his role as a bridge between the technical and the aesthetic. Underiner considers himself a translator, from zeros and ones to a print.

As I mentioned above, talking to Underiner was like talking to a mystic. He spoke of the magic in seeing an image come to life in a bath of chemicals, rising from the blank paper. He told me that since the rise of digital, he's spent his career trying to get pixels to look like silver, to make staccato, on or off ones and zeros behave like the gradation of light along with its almost imperceptible shift from light to dark.

Lynn Johnson. The type of work Underiner works to translate in print.

Sometimes, you have to tell a little bit of a lie in the midtones in order to tell the truth in the shadows.

When our conversation turned to shooting, editing or printing in HDR to get around digital's limitations, Underiner suggested that HDR rings false. Underiner explained that it looks soft in that it doesn't sharpen your attention. To Underiner, it doesn't have any edge; it's a poor translation, like reading a Neruda as a word-for-word translation and lacking the poetry.

Lynn Johnson. Underiner helping to tell lies in the shadows.

The paper was built to translate the negative into a positive so that the resulting print was a decent translation.

Like a negative, the digital image is only a partial product. You also need ink and paper to finish telling your story. From master printer Tom Underiner's's perspective, that's what makes Hahnemühle such a great producer, they understand this equation, and they're always working on the paper side of the equation to get the best out of your pixels.

Hahnemühle is manufacturing something that many might think of as a commodity, but to them, it’s something sacred. Hahnemühle sees it as being part of the creation of something.

The question left here, though, is it possible to make digital prints look like traditional optical prints?

Even after creating a closed loop calibration system and doing tests of ink and paper I've never really been happy with the prints compared to the color and contrast of the digital image. This has been a bigger issue when using "art papers" which never approach the contrast and detail of optical prints.

Then it was pointed out to me that a person viewing a print doesn't have the benefit of comparing to the digital/original image so I need to stop comparing and treat the digital print as it's own medium. It's just a different way to tell the story.

I sometimes compare my own scanned digital and optical B&W prints from the same negative side-by-side, and I'm often surprised at how similar they look.

That’s an interesting approach. I like how you phrased that. They really are different mediums!

You have to be sure that both your printer and monitor are calibrated and that you're using the right profile with your paper. I've gotten prints that look exactly like what I see on screen using hahnemuhle. Much more accurate and sharp. The amount of pixels that your camera is capable of plays a part too, if you print larger than what your camera is capable of then you won't have nearly the satisfaction looking at it close up. At a distance maybe.

At the end of the day they are different mediums as ink will spread when it hits the page where that's never an issue with pixels.

It's a process - but, worth it! I really do find the need to mix science and art to be exactly what photography is all about.

I love their German Etching paper and Matte Photo Rag. I usually use Canson paper but I like Hahnemuhle a lot as well.

I've been trying different brands recently, but always return to Hahnemühle. I mostly print things shot on B&W film and scanned, though. For me, Hahnemühle prints are like an optical print, but often a little better (but my optical printing skills aren't at a very high level).

While writing this series and talking to people at Hahnemüle as well as those who use Hahnemüle, I’ve been convinced that love of your craft and hard work can make a difference.

Hahnemüle really does seem to be doing something right!

I'm a fotospeed paper guy.

A few facts you must accept.

Super luminous colours don't exist. Ultra lime green? Super highlighter yellow? Not happening at home or office print. If you got a printer that allows you to mix your own ink then yes it's possible but very very very very very expensive process and not worth it.

There's going to be a relative or perceptual shift in the colour of your print. As in your going to shift the whole photos colour gamut to fit the paper or the out of gamut colours are going to be pushed inwards.

Your lexicon is going to increase in size, profiling, ICC, gamut, rendering intent, clipping.

Your print will never be as bright/contrasty/sarurated as your monitors. Period. Even dulled down to it's maximum it's still back lit. Paper reflects light from the source into your eyes. It's only as beautiful to look at as the light that you have. Nothing beats natural light on a sunny day.

Once you accept these you can make incredible prints. Printing from home allows so many creative options. Matte paper for moody prints, lustre for vibrant prints, glossy for green and blue landscapes.

The papers colour can massively influence the output of the print.

But as you print more and print big you will see small details you missed while editing the photo. This was true for me when I looked at the print and thought shame the print had runny ink. I looked at my monitor it was literally on the digital file of dried water stain I didn't notice!

For some printing is the end of the journey for a photo.

Great comment!

As Tom says, sometimes you have to lie a bit in your print here or there to tell the biggest truth you can.