Do you want perfect photos? If so, then maybe you are barking up the wrong tree. In your quest for perfection, you are losing an essential element from your images.

Strict rules were put in place by the earliest experimenters right from the start of photography. When Nicéphore Niépce, the French inventor of photography, said his aim was “to copy nature in all its truthfulness,” accuracy was at the forefront of his mind. He wrote to his brother in 1816 about his successes in creating negative prints using a camera obscura, saying he must give more sharpness to the representation of the subjects. Does that sound familiar?

This was an early indication of the attitude toward perfection during the period the French now call La Belle Époque. Perfection through precision was the driving force behind the early growth of photography with that scientific approach considered more important than artistic expression. It’s an attitude that dominates today.

The earliest surviving heliograph from 1827 by Nicéphore Niépce (Public Domain)

At the same time, photography became the democratizing force behind portraiture. Whereas before, oil-painted portraits had been hugely expensive and the preserve of the aristocracy, portraits suddenly became widely available.

Although those early images were very well composed, the poses were usually stiff and unnatural. That was partly because of the length of the exposure that required people to maintain a still pose. Those early photographs are often seen as formal and aloof. However, that style cohered well with the demand for realism in the images.

Like the images at the top of this article, this is part of a collection of family photographs from the late 1800s that I will be restoring before they degrade too far.

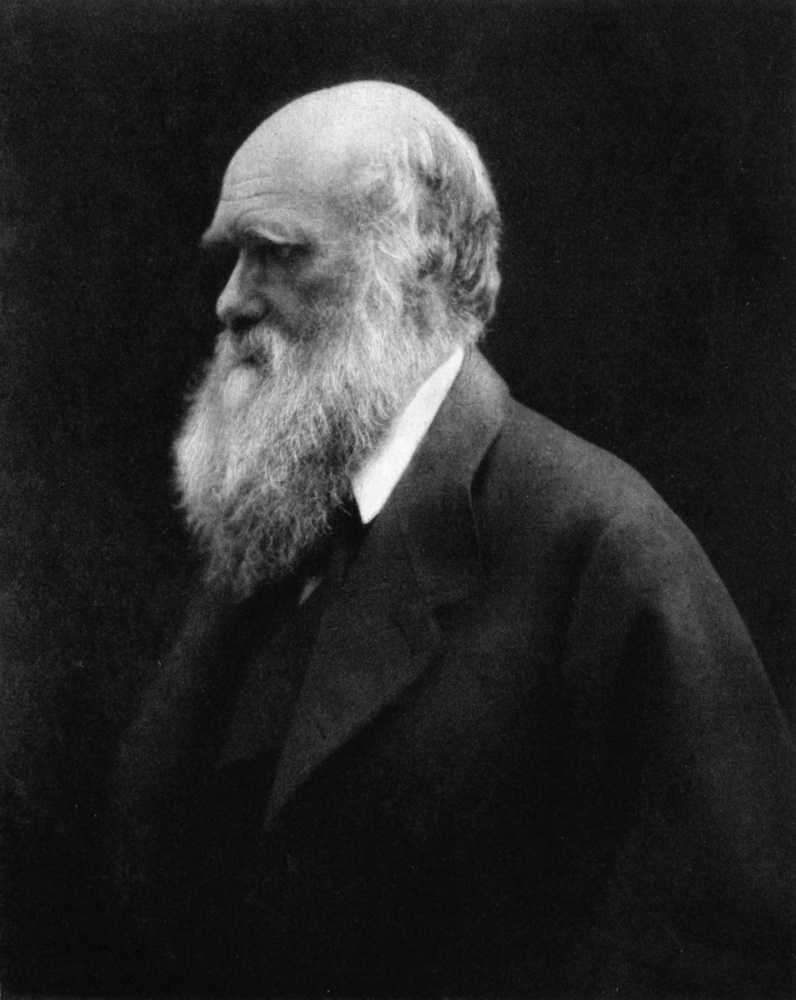

There were those who rebelled against this approach. Julia Margaret Cameron, on her 48th birthday in 1863, was given a camera by her daughter. She became prolific during the remaining 11 years of her life. Sometimes adopting a soft-focus style, her work was derided by her contemporaries, who called it slovenly. Whether the gentle, dreamlike quality of her photos was deliberate or the result of an inability to achieve precision is sometimes still debated. However, I believe it was deliberate as she also produced highly acclaimed portraits of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Sir John Herschel, Charles Darwin, and Edgar Allan Poe. So, maybe the criticisms were misogynistic.

Soft focus image by Julia Margaret Cameron "Maud, There has Fallen a Splendid Tear From the Passion Flower at the Gate" 1875. Comparing her superior images with the mediocre family snaps I've posted here and there is little doubt in my mind of her creative and technical talent.

Technical imperfections in photography, though once frowned upon, changed to become accepted or even celebrated over time.

Look at Robert Capa’s renowned photographs of the Omaha Beach D-Day landings in Normandy during the Second World War. Many of those images are of poor quality if judged by the technical standards of the day. Yet, the images blurred with camera shake add a feeling of danger and desperation to the photos, conveying the dangerous atmosphere of the battleground.

Henri Cartier-Bresson's most famous image, Derrière la Gare Saint-Lazare, Paris, France, 1932, is another example. The subject appears blurred, yet there is no denying that it’s a great photo, a perfect illustration of his decisive moment.

Sticking with Magnum photographers, one of Eve Arnold’s classic photos is of Marilyn Monroe fixing her hair in a bathroom. Technically, the image is poor. The composition is odd, the camera angle is skewed, and Monroe’s hands, left elbow, and foot are partially cropped. Yet, it captures an intimate moment in the life of an iconic figure in a private moment. The subject becomes all-important, and the technicalities of photography are inconsequential.

If we go to the other extreme, Ansel Adam’s photos seem driven by a desire to achieve perfection. His compositions and his pursuit of perfect tones are rarely criticized today. In the context of the time they were taken, when considered alongside the capabilities of contemporary technology, the flawlessness of his photos was a marque of high achievement. However, there was an argument brewing between perfectionists and those with a more casual style.

At that time the Swiss documentary and Harper's Bazaar fashion photographer, Robert Frank, published his ground-breaking book, Les Américains.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson by Julia Margaret Cameron (1869)

On one hand, Frank was praised for his casual style and lack of interest in achieving the same tonal precision as Adams. His work highlighted the bleak lives of the ordinary American people and his disregard for technical excellence worked well with that topic. But that style also came under criticism from the photographic establishment. Frank’s images were condemned by the editor of the magazine Popular Photography as comprising a “meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons, and general sloppiness.”

Meanwhile, photographer Elliott Erwitt said Frank’s work was far superior to that of Adams, whose images, he said, had the “quality of a postcard.” Maybe he was right, on the shelves above my work desk is a small book titled “Ansel Adams. Winter Photographs. A Postcard Folio Book.”

Here lies a dichotomy. Firstly, we have images that are challenging in their telling of their stories. They are technically imperfect, but that imperfection is part of the story. Then, we have the precisely made photographs that are pleasing to look at. However, they lack the same immediacy and intimacy. They make little demand of the viewer. In perfect photos, one is taken in by the beauty of the photograph and not by the subject itself.

Currently, the photographic community is swayed toward technical perfection. This is partly because perfect images are easier to like and don’t necessarily require the academic capacity to enjoy them. There is nothing wrong with that. After all, most professional photographers are shooting to please clients – clients want that technical perfection – and enthusiasts are trying to please Instagram. Furthermore, judges of photographic competitions concentrate on the technical prowess of the photographer and seldom award those whose photos have meaningless blur and drunken horizons.

The other reason for the dominance of attempted perfection is due to what controls photography today: the camera manufacturers. Every other art is driven by the art itself and not by the instruments used to create it. Painters don’t get hung up on the brushes they use but on the images that they produce. Similarly, musicians love their instruments, but their driving force is their music. They are not universally fanatical about any single brand of piano, violin, or drum in the same way as photographers are with their cameras.

Charles Darwin by Julia Margaret Cameron (1892)

It’s the competition and the manufacturers’ powerful marketing behind zealous extremism towards camera brands. They encourage a following with a cult-like fervor and, as surely as people are taken in by high-demand fundamentalist religions, people get hooked on camera brands. Those manufacturers promise the paradise of ever-greater resolution and tell photographers that they must upgrade to achieve perfection.

My evidence for this? If I write an article about a camera, then that will get thousands more readers than my articles about using art techniques in photography. If I dare criticize any of the big three brands, I am guaranteed to get trolled, and my inbox will receive hate mail. I wish they put as much passion into their photography as they do when worshiping their camera gods, then they would take far better images. Sadly, many photographers are far more concerned about the camera they are using than the art they are creating.

There’s room to explore both extremes. Some of the very best photographers do just that. They mix their carefully constructed photos with spontaneous shots that care little for the technicalities. Their aesthetically pleasing, well-composed pictures keep the masses and camera club judges happy. Meanwhile, artists and collectors are absorbed by those images that are more interesting and less likely to have widespread appeal.

Julia Margaret Cameron's portrait of the Sir John Herschel, (1867), who himself was an active photographer who invented the cyanotype.

I hope that we will see a swing away from that drive for perfection to the more interesting. Why? Perfection is becoming boring. There is so much similarity with everyone trying to achieve the same product. Photography has become a sausage machine. It would be great to see more spontaneous, interestingly unique, flawed pictures alongside perfection.

Finally, very rarely, there are exceptional photos that were taken spontaneously, but are also perfectly composed and exposed, and are pin sharp in the right places. Do you have any of those in your portfolio?

What’s your photographic style? Are you driven towards perfection? Do you get hot under the collar if someone criticized your camera’s brand? Or, do you explore the world and not give two hoots about the rules and expectations of the establishment? It would be great to hear your thoughts.

I think this is why I keep finding myself so drawn to pinhole photography. I mostly shoot nature. I buy prime lenses for my cameras because I want the best sharpness possible. I stress about technique. I shoot large format frequently. I have calibrated my processes for the Zone System. I do all those things, and most of the photos I like in my own portfolio are ones where I have successfully executed something artistic with a high degree of technical competence.

And I can count on two fingers the number of pinhole photos I've taken myself that I actually like at all. But I can't get enough of seeing the pinhole photography of others, and I think it's because it's a nice break from all the cookie-cutter landscapes I see everywhere.

It's a good sign when we find others' photos more inspiring than our own. It means that we can carry on improving. Thanks for the great comment.

Interesting photos. We get caught up on Lightroom, Photoshop and any other method of editing. I'm always intrigued by the photos of the past. B&W was all they had and did the best with it. Robert Capa's photos were especially interesting. My father's oldest brother was in the first wave at Omaha, I'm told. Trivia: There was a photo of a guy on a stretcher, moving toward the still camera. He has a pencil style moustache per Clark Gable. He is on his left elbow and looking at the camera. To his dying day, my father swore that was his older brother.