We've briefly covered the release of this very special filter before. It blocks out the artificial light of our modern world, light pollution. STC's Astro-Multispectra Filter is designed to block out the orange and green hues from sodium and mercury street lamps. But what's really intriguing for any Nikon full-frame shooter is that this is the first and only option when you shoot wide-angle landscape shots.

Special indeed. This is a so-called clip-in filter that attaches directly to the sensor. Well, sort of. It sits on top of the sensor.

To install the Astro-Multispectra, you have to lock up the mirror. And shooting is only available in Live View, because the filter is in the way of the mirror. That being said, the viewfinder is useless anyway when shooting astro landscapes (nightscapes) or genuine astrophotography. At night, it's just too dark to distinguish features to judge if a composition works or not. So, you will not be giving up the optical viewfinder for the filter, but for the genre.

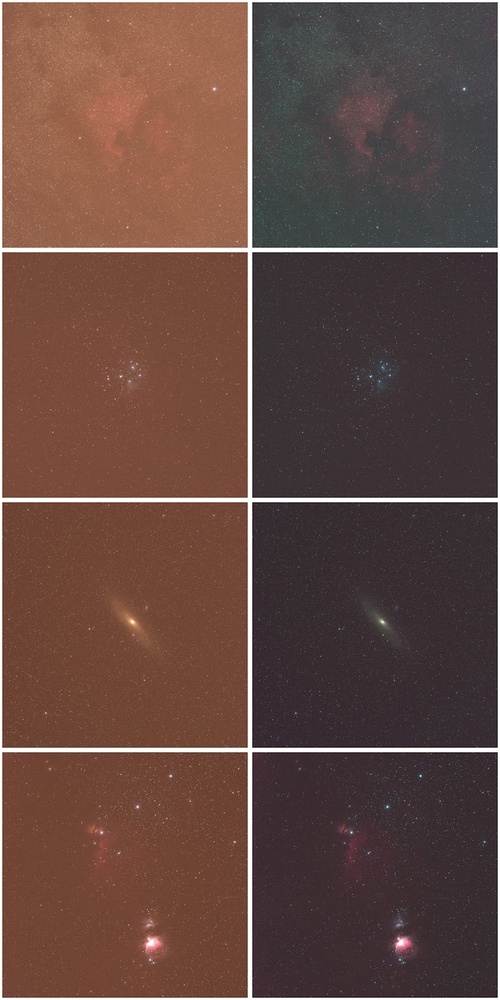

Here's how what to expect from the results when you compare shots taken with and without the Astro-Multispectra Filter:

Frequency

So, how does it work? Well, light comes in different shapes and energies. What we perceive as colors are actually different frequencies of visible light. Different sources are responsible for different colors. And since our night is illuminated by mostly sodium and mercury streetlamps, we can very effectively block out those colors when we photograph the night sky.

The dips in this graph represent what frequencies are filtered out. The huge gap in the ~600 nanometer range shows that this filter works particularly well in light polluted areas.

Orion Belt by Jerry Huang using STC Astro-Multispectra Clip filter Camera: Nikon D800 Modified Lens, Carl Zeiss Zeiss Apo Sonnar T* 2/135 ZE

Either it reminds you of Pink Floyd, or an experiment at school. The prism shows how white light breaks into the colors of the rainbow: All visible colors.

Dark Skies and LED

You can of course head over to the more rural or protected areas to avoid light pollution altogether. There are many more interesting foreground subjects in those locations anyway. So, it begs the question of necessity of light pollution filters. Are we getting too lazy to go to the nearest dark sky site?

Well, we are rapidly losing the night sky. Earth is rapidly becoming more and more overpopulated, and our activity never ceases, even at night. That's much to the detriment of the natural world, since many species of animals and even plants cannot cope with artificial lighting. Luckily, there are alternatives to lighting our nights with high-pressure sodium vapor lamps, like LED lights. But those can be even brighter, and the jury is still out if LED is a good replacement if we strictly look at its effects on affected flora and fauna. LEDs are also more blue and produce a wider emission line than sodium or mercury lamps, so taking pictures around LED street lamps with one of these filters may not be a good idea.

LED lighting will eventually replace most of the artificial light around the globe. From an energy-saving perspective, that's a good thing. But how long will this $185-filter be useful?

We will be reviewing the use and quality of the filter when it arrives in multiple scenarios. In the mean time, what would you like to see me photograph with this filter?

I am afraid to put anything of this sort on top of my Nikon D810's sensor. Can someone else try it on there D810 and let me know? :)

I'm going to. On top of my D750. :)

And yes, I'll let you know!

Thanks, I hope it works on your D750.

I want to shoot more astro but finding a location that doesn't have light pollution and one that isn't ~50 miles away is challenging.

Yeah, I know exactly what you mean... And it's not just the fact that these places are ~50 miles away. Taken into account that you'd actually have to stay overnight makes it a hard genre of photography to combine with any other daily activities.

Good start to a real world test for the sensor filter! I would be interested in a test of the LED light pollution if you could pull it off? Below is a photo I took of a lake in a dark sky preserve close to my town, you can barely make out the milky way in the top left corner. Most of the cities here are changing to LEDs to save money, so a sodium/mercury filter will do me no good.

Wow, that light pollution is horrendous. It would be hard for any filter to peer through that, honestly. There are places that I know of that have LED light fittings, so I will give it a go there as well.

You can start to see that LED really isn't the answer to combat light pollution.

Do be aware that I'm testing this in spring, so the Milky Way (at least the central bulge) will not be visible throughout my test shots. I plan on using it to image the other side: Orion and Barnard's Loop - possibly with the aid of an astrophotography tracker, reviewed separately. ;)

Thank you!

Interesting ! Thanks for sharing this information

I wonder, once the filter is installed the camera can not be turned off without damaging the mirror ?

Went to the STC web site, they also offer a filter that goes on the lens ... bigger and more expensive, besides price what would be the advantage of using the filter inside the mirror box ?

Thanks a lot for the input, Armando. We're going to cover these things in the review. I would just like to shoot a couple of tracked deep sky images and we're done. :)

Appreciate the patience. haha!