Exposure bracketing is one of the most important tools to know how to use for landscape photography and is likely a term you've heard from every major name in the business. Find out why it's so important and just how easy it is to learn.

Whether you're new to landscape photography or a seasoned veteran, exposure bracketing is likely the most important tool you'll use out in the field. Personally, I use it constantly even though as technology has advanced, it's not as necessary, I find myself still exposure bracketing more often than not. One of my favorite aspects of exposure bracketing is using it to breathe life into an older camera system. Within the video above, I go into detail on taking an exposure bracket, and I specifically compare an image from my nearly decade-old Canon 6D to a Canon R5 to show just how much bracketing can change your photography no matter what camera you're using.

If you're more of a text reader, I cover everything you need to know within this article as well, including what exposure bracketing is, why we need to use it in landscape photography, and exactly how to do it.

Why Exposure Bracket?

I've seen quite a few tutorials explain how to exposure bracket, but they never cover why. I think it's really important to understand why you are doing something rather than just doing it because someone told you it's important. The human eye is estimated to be able to see up to 30 stops of dynamic range. Dynamic range is the measured amount of light between the darkest part and brightest part of a scene. Thus, the higher the dynamic range, the wider amount of luminance values you can retain in an image.

Notice the camera captured the bright outdoor areas but barely any details inside

If this is confusing, think about it like this. Take your phone to a bright window on your house and take a picture, making sure to leave part of the framing in the picture. You’ll notice that your eyes can see everything in the scene; they can see outside in the bright areas and even the inside dark areas of the frame, but your phone can’t capture all of those details. This is because your eyes can see a much larger range of luminance than your phone can, thus your eyes have a much wider dynamic range.

Regardless of if you're shooting photos with a phone or a brand new high-end camera, this example can also be used to explain exactly why to exposure bracket, simply because some scenes are too bright and simultaneously too dark to be captured all in a single photograph because our cameras lack the dynamic range to see everything.

How to Exposure Bracket

Gear you'll need to properly exposure bracket

There are two ways to exposure bracket a scene, and I'll start by explaining the manual method, which every camera is capable of doing no matter the brand or cost. Here is what you'll need:

- A camera that can adjust ISO, shutter speed, and aperture.

- A tripod or stable spot for your camera to rest.

- Preferably a two-second timer or cable shutter release.

Once you've found a composition you're happy with and your camera is locked into position, all you need to do to exposure bracket is take multiple exposures of the same scene at different exposures. Simple, right? Yes, but there are rules you'll need to follow to make sure to take your shots properly:

- Only change the shutter speed to adjust your exposure, which is one reason you need a tripod in the event your shutter speeds get lengthy. If you adjust the aperture, you risk slight focus breathing and having your images not align in post. If you adjust ISO, it can change the color rendition or add noise to your image. You'll want to be in manual mode on your camera so your ISO and aperture don't automatically adjust.

- Use manual focus once you have focused your scene. This will prevent your camera from continually autofocusing between exposures, which can cause slight shifts between exposures.

- Two-second timer or cable release: you want to take your photos as fast as possible so things like clouds in the sky don’t move much but you also have to be careful not to shake your camera between exposures. A good way to do this is to use a cable release or at least a timer for your shot.

- Take the shot(s). If I plan on taking three exposures with an exposure difference of 2 EV, I will meter my scene until the exposure is at 0 EV and take my first shot. Quickly increasing the shutter speed until the scene meters at -2 EV, take a shot. Finally, decreasing the shutter speed until the scene meters +2 EV to take the last shot. Note that a lot of camera's have a built-in function that will do this automatically for you, as discussed below.

That's it; you've taken your first exposure bracket! Now that you understand how to do it manually, let's go over the other and much easier way to exposure bracket in the field. It's important to follow the rules above regardless of you're taking the shots manually or not. I won't be able to show you exactly how to set up your camera to exposure bracket, because it will depend on the manufacturer of your camera, but I'll go over the two main settings you'll set using my Canon 5D Mark IV as an example:

Number of exposures

Choose how many exposures you want your camera to take. The first decision you'll make is telling your camera how many exposures you want to take. Typically, this is 3, 5, 7, 9, or even 11. Personally, I only take three exposures; every so often, I'll take five. In Photographing the World Part One, Elia takes nine exposures at one point. This decision will ultimately depend on your camera's dynamic range and the scene you're taking. I highly suggest starting with three exposures and increasing if the scene has crazy dynamic range.

Amount of exposure between each shot, in this case -2EV, 0EV, 2EV

Choose exposure separation. Setting this will tell your camera how far apart you want each exposure to be. This is typically two stops or one stop in my experience. Most cameras can recover close to one stop of light, so 99% of the time, I use at least 2 EV of separation.

Once you have those two settings changed, then your camera will do the rest, meaning you don't have to touch it in-between shots and will take the different exposures much faster. This will give you more successfully bracketed exposures and overall just makes life a lot easier.

Editing and Conclusion

Now, that you've taken your exposure-bracketed photos, what can you do with them? There are two methods to edit multiple exposures together, luminosity/exposure blending or converting your image to High Dynamic Range (HDR). This article isn't intended to cover those topics, as they both deserve an entire article themselves. If you're interested in learning about exposure blending you can check out my video on the topic or skim through older live streams I've done, as I use the method quite often.

Select Photos > Right Click > Photo Merge > HDR

If you'd like to simply convert your exposure-bracketed photos to an HDR image, all you need is software capable of doing so. If you're using Lightroom, all you'll need to do is select your images, then right-click > photo merge > HDR.

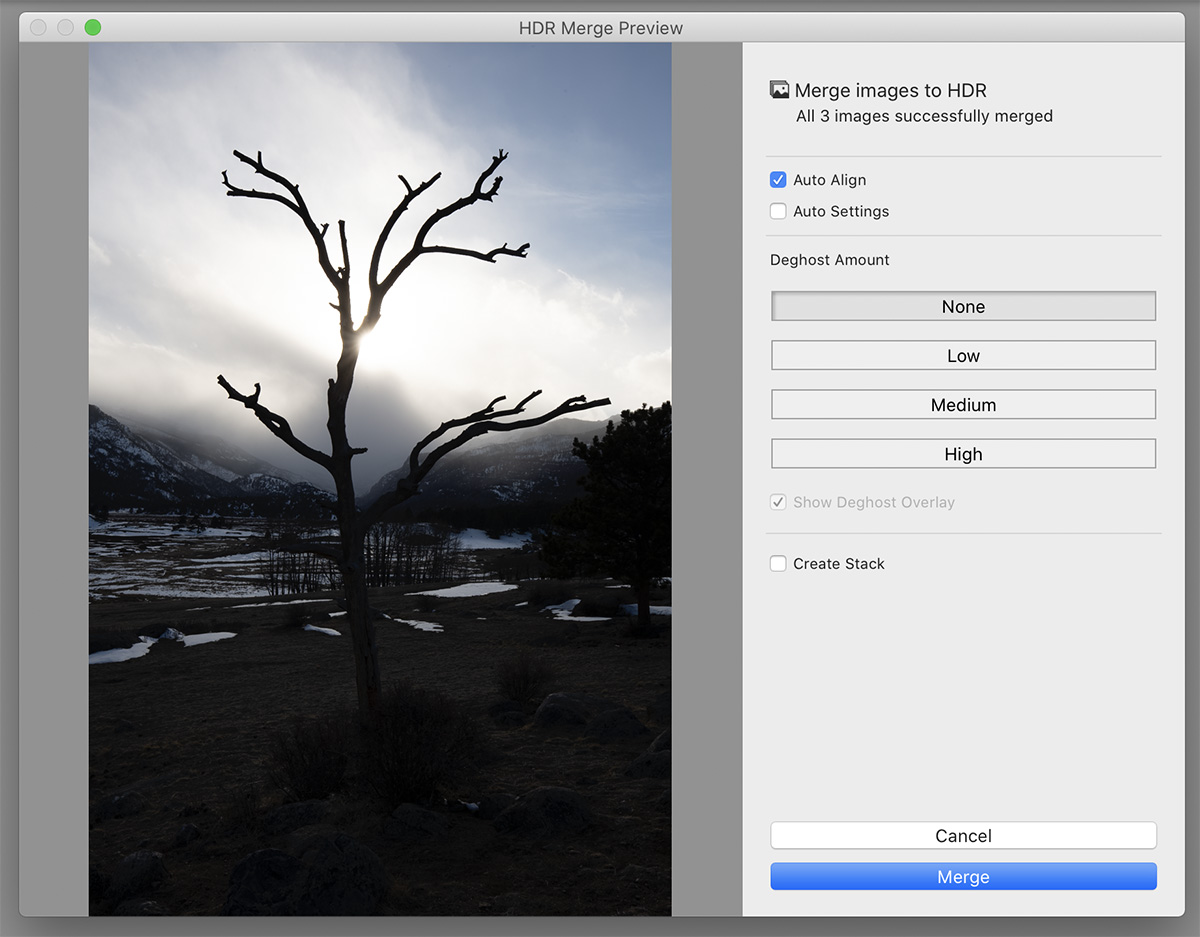

Create a stack for organizational purposes (my normal settings)

This will bring up a menu where you want to make sure "Auto Align" is checked, Deghost amount should typically be set to none or low if you follow the rules in this article. Then, click merge. This will give you an image that looks very similar to your correctly exposed image but should contain much more data when you adjust things such as highlights or shadows; try it out, and you'll be surprised how much you can do.

I hope this article or video was helpful, and if you need more information on how to take or edit your bracketed exposures, be sure to check out Photographing the World or any of the wonderful articles here on Fstoppers. As always, I'd love to hear your thoughts down below. If you have any questions regarding exposure bracketing or feel lost on what to do with them after you've taken them, just ask in the comments.

this was a really in depth article talking about exposure bracketing Alex Armitage you really did a good job with this one

Thank you Tdot!

Some research says the Human Eye in idea conditions can see up or over 20 stops of dynamic range I found one touting 24 stops just wondering can we really see 30 stops or more?

It's less about how much the human eye and see, and more about capturing as much data as you can to have the flexibility you need in post to art-direct your shot the way you want it to.

Great video Alex! Subbed!

Thanks William and welcome! :)

I think the estimation is mixed and you can find varying amounts. That said one thing I didn't go into detail here is your eyes can't see 30 stops at a single time and they actually see a much smaller range but are able to interpret multiple ranges and combine them without us knowing.

24 stops is a perfectly reasonable estimation as well.

One thing we're forgetting about the eye's dynamic range is how much the brain helps to in fill in the missing pieces.

Been using this technique for years to photograph with Micro Four Thirds cameras contrasty landscapes that would have exceeded the DR of a single-shot capture from even the best cameras available today. Combine this with stitching for a file with more pixels as well as more DR. I've even gotten good results with my ultra-compact Panasonic LF1, using its long 200mm EFL zoom to break up the scene into many smaller parts and then stitching into a very large file. At the pixel level, IQ is not amazing, but with sufficient pixels for a target print size, this doesn't matter.

Under the right conditions, these two techniques can enable really amazing technical quality even from smaller-format cameras.

It really can bring out incredible image quality from a ton of cameras.