Tilt-shift lenses are often thought of as specialist glass destined for only architecture, but their high-quality optics and magical results actually make them perfect portrait lenses.

You could be forgiven for equating the tilt-shift lens with architecture. After all, they're incredibly useful for correcting optical distortions that plague the architectural photographer when trying to capture buildings accurately. But the shifted plane of focus from the tilt and the corrective qualities of the shift actually lend themselves to portrait photographs rather favorably.

Aperture affects depth of field and shutter speed alters how motion is captured in a shot, but tilt-shift lenses bring another two dimensions to the portrait game. If you're wanting to mix things up or even create a new style that's a step away from every other portrait photographer out there, then a tilt-shift lens might be just what you need to capture something a little more unique. Sure, tilt-shift lenses can be quite expensive if you're not looking to buy one anyway, so another option is to hire a lens from a camera gear rental specialist such as Lens Rentals. This helps reduce the cost dramatically, perfect for experimenting with a new technique or if you have just one photo job to do but don't want to invest in new kit. Tilt-shift lenses are often known for correcting parallax issues, but what is it and how does it work for portraits?

Correct Parallax Distortion

Much like shooting architecture, a tilt-shift lens is great for correcting the parallax distortion you get when shooting tall things from a low angle. This distortion manifests as the subject appearing to lean away from the camera. A tilt-shift lens corrects this by physically shifting the lens relative to the image sensor plane to expand one side of the frame and regain that lost shape. Here, I photographed a portrait from a low angle without the shift and noticed my subject was appearing to lean back in the frame, so I added some positive shift to correct this and make her appear more upright.

Control Plane of Focus

We can see the plane of focus being tilted away from the camera here. At the bottom, my subject is blurred, while her head and the higher-up, more distant branches are both in focus.

One benefit of shooting portraits with a tilt-shift lens is that you can introduce a shallower depth of field without having to alter your exposure settings. For example, say you have an aperture of f/5.6, a shutter speed of 1/200 sec, and ISO 100. You've found that this exposure gives good, clear results, but you'd rather have a shallower depth of field. Instead of opening the aperture and then having to re-balance the other settings, you can just add some tilt to the lens, which produces an apparent shallow depth of field if oriented the right way on the camera body. Now, you can switch between tilted photos and standard photos without changing exposure settings.

Magical Results Like Nothing Else

Let's compare two images, both taken on the same lens but one with no tilt and the other with full tilt. Shot at f/2.8, we can see that the photo with no tilt does have a shallow depth of field with the subject sharp but the background falling out of focus. Now, this is great if all you want is a nice blurry backdrop with your subject sharp. However, what if you want to be more selective with the focus?

In the tilted portrait, we can see that the bottom of the frame is now out of focus, with a graceful gradient towards the eyes that are then rendered sharply. The added advantage of shooting this portrait with a tilt on the lens is that not only can you determine the depth of field, which keeps the attention on the subject rather than a distracting background, but you can also create sharper elements that move towards the foreground. To see what I mean, take a look at the top of the frame in this tilted image. There are some overhanging branches that are more in focus than in the non-tilted shot. Whether you want this depends on whether or not these elements are important or not. In this photo, I personally prefer it because it hints at the context of the scene without fully revealing it.

Difficult to Replicate Digitally

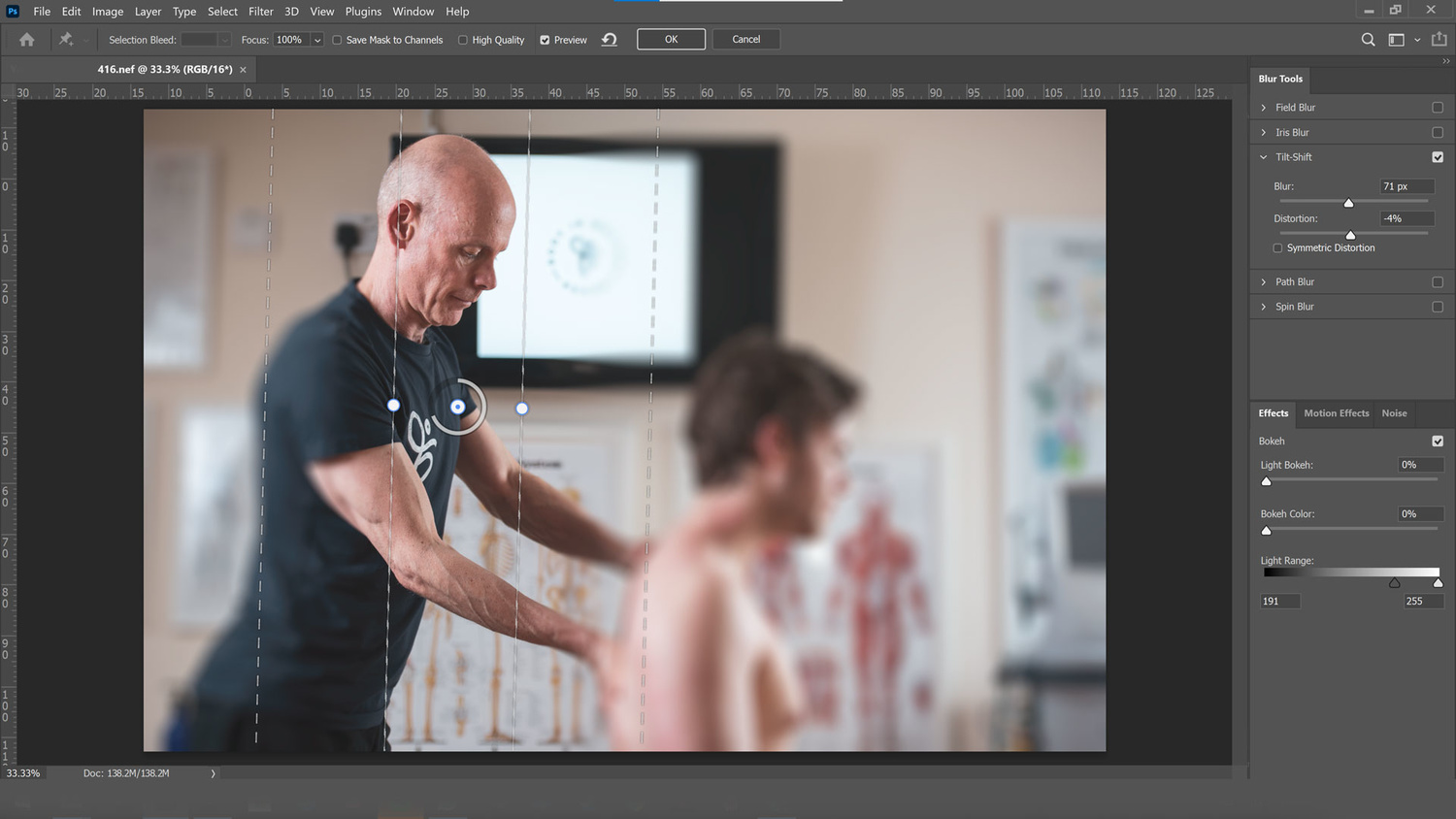

Although it's possible to emulate the tilt-shift effect with software (which I demonstrated in another post), it might take you a while to fully realize the proper effect. In fact, it may even be impossible. As the tilt-shift lens tilts, the plane of focus (that slice of the depth of field you have) goes from being upright (the same orientation as your image sensor) to tilted. This places the focus across a specific angle of your scene. Editing software simply applies a blur from top to bottom of an image regardless of the distance from the lens.

Applying a tilt-shift blur in Photoshop CC is actually pretty easy and takes next to no time at all, but a true tilt-shift lens doesn't behave in the same way because the software is applying blur to the entire frame regardless of distance from the lens.

To correct this in the software, you'll have to do a lot of masking to ensure the plane of focus is uniform throughout the scene. Even then, you may not fully mask the scene, at least perhaps not as accurately as you can with a tilt-shift. With the lens, you can take this kind of picture with ease, then turn around and shoot another one, and another one. Yes, you could do this in software to give a similar effect, but would you bother doing it across tens or hundreds of shots?

The Downsides

Of course, there are a few drawbacks to shooting on a tilt-shift lens. Though nothing major, it's something to be aware of. Manual focus is the norm with tilt-shift lenses, so you'll have to get used to focusing with the ring on the lens, rather than relying on autofocus. That means faster-paced shoots or action shots are probably going to need a little more preparation with a pre-placed focus point, rather than having the ability to follow the action. However, the longer you shoot with manual focus, the better you'll be at tracking focus manually. Also, tilt-shift lenses commonly have quite a sensitive focus ring, which makes it much easier to nail focus compared with a standard lens. A large movement on the focus ring makes only small adjustments to the focus in the scene, so you can really fine-tune where you want to place focus.

I always use the cheap Lensbaby for such portraits. Fun to use, inconsistent, and not to mention that you can make a heart shaped bokeh. Nice article to read by the way.

As someone who owned all three (I still have the 24mm and 45mm, sold the 90mm) of the Canon TS lenses I found the keeping more things in focus more beneficial than the tilting things out of focus.

With portraits I like the subtle OOF effect I get from either doing it in post or using a wider open aperture on a fast 55mm or 105mm or 85mm lens. About the only thing I do is a slight tilt to soften a portion of the frame.

I realize that you were just doing some quick shots for the article but the second example is not very flattering to her, and the tree branches are tack sharp. Maybe less tilt would have been less extreme.

Either way finding the sweet spot with a TS can be tricky, a little tilt goes a long way...it's like oregano :)

I'd argue using tilt-shift for portraits is more useful for correcting distortion than weird DoF effects. But that is just me. If I want weird DoF effects I can grab a Helios or similar for a fraction of the price and a cooler effect.

I've seen really beautiful use of tilt-shift in portraits that create a very unique look though in terms of fixing distortion by keeping the sense parallel with the model. That said, for me, I'd probably find the MF too frustrating to make use of it. I do leverage vintage cool lenses from time to time and while I often like the results, the MF experience is just not for me. I am a worse photographer when I have to MF.

Again confusing perspective and parallax? Unless your camera has two sensors, or you're shooting multishot panoramas, you certainly don't need to fix any parallax issues. Parallax distortion is the one caused by the differences between two separate points of view, like stereo vision.

Please do correct your wording, else this and your last tutorials are misleading. I had a look at some courses offered paid here, but if this is the care taken in those, I'd rather buy a proper book.

Yes, there is no such thing as parallax distortion. He seems to confuse it with parallax shift. But I rather think he does not really know what he is talking about. Articles by this author are at the lower end of the quality scale of all articles on FS.

And so are his pictures.

https://youtu.be/G2y8Sx4B2Sk

This man fundamentally doesn't understand the tilt-shift principle. Or if he does, he's communicating it very badly. He confuses parallax with converging parallels and then suggests (in 2 articles) that simply shifting the lens corrects converting parallels. It doesn't.

In his example of the woman and the tree, the first shot is a result of the camera angled upwards. Angling the camera so that it is not parallel to its subject is what causes converging parallels. To achieve the 2nd shot, the camera MUST first be levelled vertically. Then, and only then, should the lens be shifted up or down to reframe the subject. It is because the camera is parallel to the subject that parallels no longer converge. It is NOT because the lens has been shifted. Shift is a re-composition tool. Nothing more.

I'd hate to pay for his courses and be spun this circle of confusion.

Judging by the cover image that TS-E 50mm 2.8 is huge. I think personally tilt does not add much to portrait images.

Ha. Good luck with getting portrait photographers to a) learn how to use these lenses, b) spending the time in a photoshoot to making the adjustments. They are not easy lenses to use.

You can also learn how to "lens whack" with a much cheaper vintage lens. You'll end up with very similar results, and a dirty sensor afterwards!

I know this article is about shooting portraits, but, T/S lens's are very useful for landscape and Still-Life studio work, increasing the resolution by stitching three shots.

Maybe it's just me, but I understand wanting to shift the scene in order to place the person you're photographing better in the frame without distorting the scene too much. But the tilting effect looks horrible.