Mastery of the camera, a keen photographic eye, and excellent timing are all prerequisites for being a good portrait photographer. But there’s another quality that is much harder to come by and less often talked about, yet it can distinguish a great portrait photographer from a good one.

Ask any consummate portrait photographer what it takes to create a great portrait, and it’s more than likely that the ability to establish a connection with the subject will rank very high on that list. The ability to connect with people, to put them at ease and make them feel comfortable around you, is a game changer in any endeavor that involves working with others. It is key to success wherever trust and cooperation are essential, and nowhere is this more true than in portrait photography.

To get a great portrait, you need to bring out the best in the people you are photographing.

Born in 1954, photographer Sage Sohier has forged a career capturing beautiful and intimate portraits of people in the places where they live and work. The most striking aspect of her portraits is how natural and unposed they feel, and above all, how intimate. Sohier’s photographs convey the feeling that these people are not strangers but rather people you know—as if you, the viewer, were there hanging out with them yourself.

Despite originating in an age before phone cameras, these portraits feel as natural and spontaneous as the kind of images that somebody in a group of friends or a family would capture on their phone as a visual memory—yet the people in Sohier’s photographs are strangers.

As you will see in this wonderful video created by Graeme Williams for his YouTube channel Photographic Conversations, aside from her evident artistry with the camera, Sohier’s great gift as a portrait photographer was her ability to approach strangers, win their trust, and make them feel comfortable with her proximity and the presence of her camera. All of this, coupled with an uncommon degree of fearlessness, made her an outstanding portrait photographer, whether she was working out in the streets or one-on-one with her subjects in a more intimate setting.

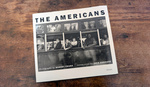

As somebody who loves film photography and black-and-white, this video was truly a treat for me, as well as offering a fascinating vignette of American life in the 1980s and 1990s.

In a perfect world, I agree 100%with the above. The ability to form some kind of relationship with your subject is often key to producing a good or great portrait. Williams produces fascinating videos on photography and are a great watch. When it comes to Sage Sohier, I find the chaos inherent in her compositions difficult to come to terms with. That I put that down to my own minimalist-leaning personal taste, and that’s fine as I can ultimately see the merit in her work. Unfortunately, in this day and age, it’s not always the nature of the image that determines how great or worthy it is in this ‘woke’ age we live in. More and more, I see who the photographer is determines the status of an image. Being a good photographer is not enough, as you need to be the right kind of photographer. Hand in hand with that is the backstory to the image. I was at a talk a few days ago given by the curator of a significant national photographic collection. He proceeded to show images from the collection, mainly portraits, and in his talk, he continually referenced the photographer as though the story of the photographer and who they were was enough to justify the inclusion of the image. He told the story of one image, not a portrait, but of rocks in a pool and how the photographer developed the image using said pool water and local vegetable-derived material to create the image. In this instance, the process trumped any visual quality of the image that was, IMO, mediocre at best. All in all, I came away with the impression that the quality of the image and any intrinsic aesthetic merit it may possess was low on the list of priorities and way behind that of the identity of the photographer, their ‘woke index,’ along with any backstory to the image. Once we enter into a situation where ‘woke standards’ are being used to determine the quality of an image, then the game is lost.