Ever felt a little overwhelmed at the prospect of creating a great image? Ever wonder why it seems to happen so rarely? Creating a great photograph that resonates with your audience is really complicated. But in this three-part series, we’re going to try to bring a little bit of order to that chaos!

In this first article, we’ll look at how our viewers may digest an image. In a second article, the levers that we as photographers have at our disposal when creating an image will be examined. In a final article, we’ll explore the connections between the two to see how we might use our understanding of image interpretation to guide the process of image creation. But first, we need to think a little bit about what we’re trying to achieve when we create an image and send it out into the world.

What Are We Trying to Accomplish With Photography?

One evening, a buddy and I had a couple of glasses of wine and a long discussion about wedding photography. His assertion was that wedding photography wasn’t and could never be art. I, on the other hand, took the (obviously correct) perspective that if a couple pays thousands of dollars for photos of their wedding day, those photos better be art. They better not just capture who was there or who blinked during which posed shots. They better capture what the day felt like. To quote Tolstoy: “… whereas by words a man transmits his thoughts to another, by means of art he transmits his feelings.” (L. Tolstoy, “What Is Art?”)

In fact, regardless of the genre, it’s rare that we’re not trying to communicate more than just the basic facts — the who, what, when, or where — with our photographs. We’re usually trying to communicate something about how the moment feels. Fellow staff writer Nils Heininger recently published a great article discussing just this difference. As Nils notes, the task of forging this link is made all the more difficult by the fact that we, as the creators of an image, and our audience, as its interpreters, will each bring our own experiences, interests, and values to the process. Yet, to be successful, it’s critical to accomplish this feat.

Images work better when they provoke an emotional response. Imagine this same scene with harsh light, washed out colors, and a bit of trash in the foreground. I suspect it wouldn’t have the same emotional tenor, and would, as a result, be a far weaker image even though it would convey roughly the same information.

It’s only through emotion that we can fully engage with our audience. If we want to bring our family, friends, or social media followers along on our travels, they need to feel what it’s like to be there. If we want to get people to drop $1,000 a night on a commercial client’s safari lodge, the photos better spark their prospective clientele’s imagination, make their hearts race a little. If we want to get people to donate to a cause, they have to empathize with the endangered, the unfortunate, the indigent. If we want people to better understand our own or someone else’s point of view, they have to understand where we’re coming from emotionally in order to be able to really empathize with us.

Art is uniquely suited to accomplish this, to communicate a wide range of emotions between artist and viewer. But that begs the question: just what is an emotion?

Emotions Are Survival Guideposts

Emotions are a mechanism that’s evolved over the millennia to guide our attention and behavior. They’re rules of thumb meant to help keep us alive, to provide a bit of accumulated insight in lieu of, or in addition to, a conscious analysis of a situation. They provide rapid feedback and a nagging incentivization that helps guide and motivate us to do things that, evolutionarily, have been good for our chances of survival and avoid situations that might be detrimental.

Emotional responses are so important to our survival that they form at many different levels within the brain, through connections at many different points in the visual pathway, and in response to many different types of stimuli.

As a byproduct of evolutionary drivers, our brains can respond emotionally to things as simple as abstract arrangements of form and color.

We might have an emotional response, a feeling of pleasantness (left, above) or unease (right), to something as simple as an abstract arrangement of lines or forms. Yet, a photograph may also elicit emotional reactions on other levels as well via the subject it depicts or the story it tells. These emotional responses are orchestrated by a portion of the brain called the limbic system.

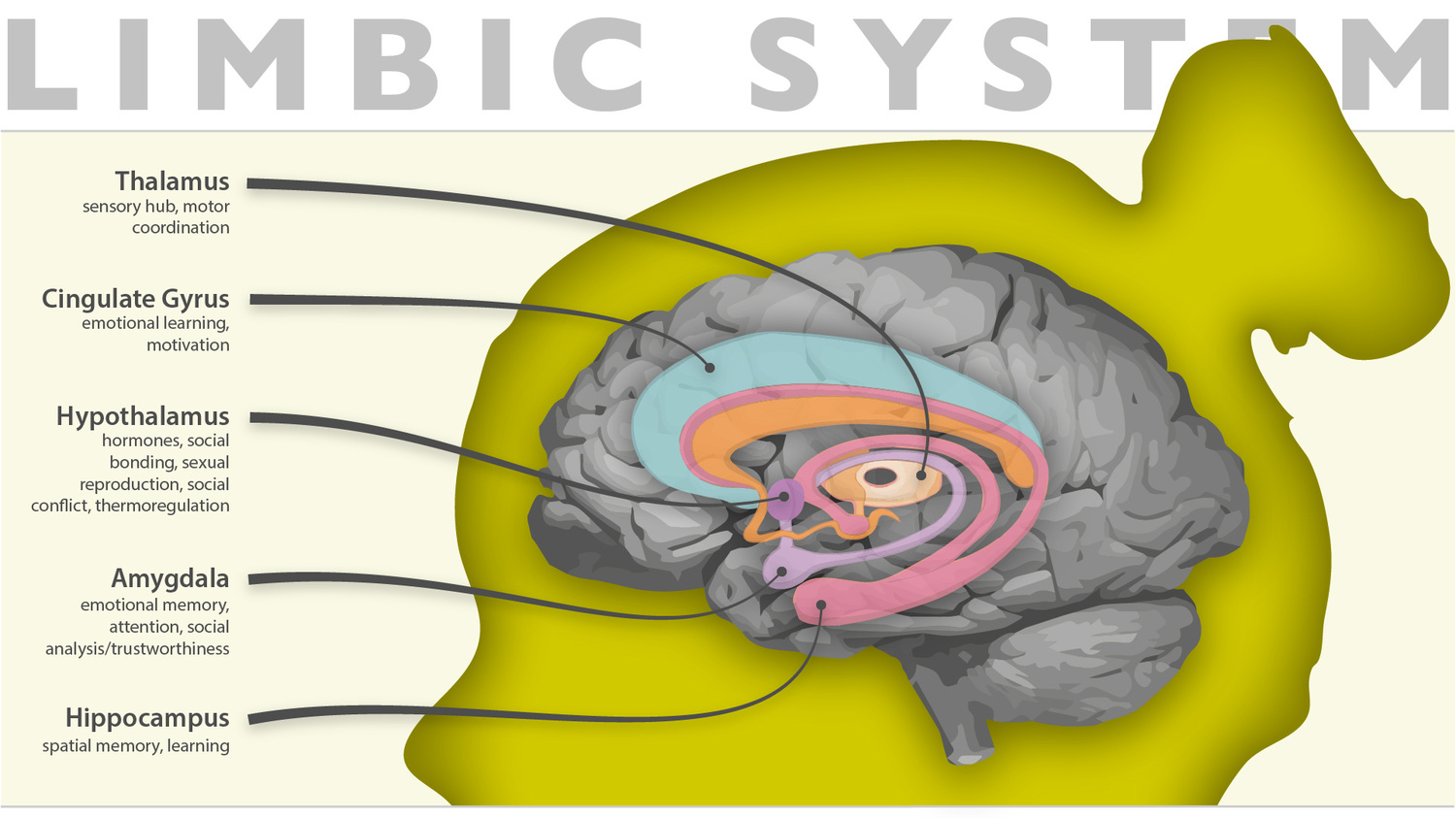

Primary components of the limbic system. The limbic system plays a critical role in determining our emotional response to situations or scenes. Limbic system structures illustration adapted from OpenStax College - Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. CC BY 3.0.

Primary components of the limbic system. The limbic system plays a critical role in determining our emotional response to situations or scenes. Limbic system structures illustration adapted from OpenStax College - Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. CC BY 3.0.

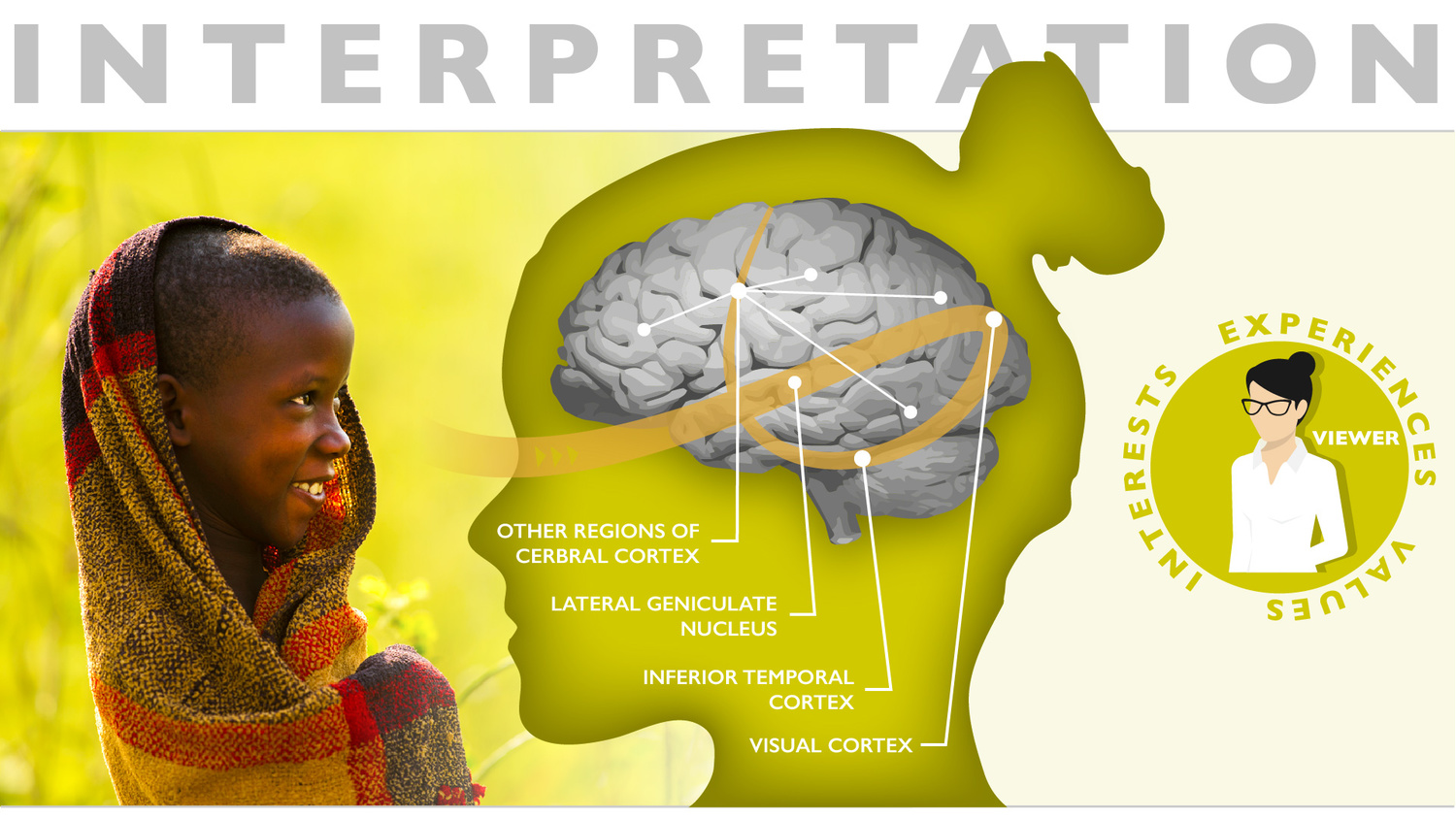

There are a couple of structures within the limbic system that are particularly relevant to visual processing. The thalamus serves as a hub for information coming in from most of the senses, including sight. In fact, a portion of the thalamus, known as the lateral geniculate nucleus, is the very first stop for signals coming from the retina. It’s there that the earliest processing of luminance and color contrast begins. From the thalamus, visual signals begin a loop out through the cerebral cortices, beginning with a region toward the back of the brain known as the visual cortex. The signal then passes on to the inferior temporal cortex, before heading out to many additional areas of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex.

At many points along this pathway, there are connections back to a second structure within the limbic system called the amygdala. The amygdala helps orchestrate our emotional memory, guide our attention, and even assess who to trust in social situations. There’s even some evidence that the size of the amygdala is correlated with creativity. These many connections to the amygdala allow the brain to form emotional reactions at many different points in the process of interpreting an image and even adjust how our attention is being directed between the different parts of a scene in real time.

Next, let’s take a quick look at the role each of the primary processing centers within the cerebral cortex plays in image interpretation. We’ll then think about how this might help us break down images to better understand how and why we respond to certain aspects of them.

Visual Processing Centers of the Brain

That a few splotches of color and tone on a two-dimensional canvas can transport us around the world, bring tears to our eyes, joy to our soul, or open up whole new perspectives on the world around us is pretty profound. It’s also a bit complicated. How do we go from an image, on the one hand, to eliciting an emotional response in our viewers on the other?

Primary regions of the brain related to visual processing.

Primary regions of the brain related to visual processing.

It turns out that the brain accomplishes this task in what is often a surprisingly logical, step-by-step fashion, extracting different types of information from an image and progressively building up meaning from successive layers of analysis. Let’s take a look at the primary locations in the brain where this happens.

Lateral Geniculate Nucleus

The first stop for signals coming from the retina is in a portion of the thalamus called the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN). Early processing of a scene is done here, extracting information about the location of edges, textures, and colors (Principles of Neural Science). The receptive field within the LGN basically mimics that of the retina. Some of the six layers within the LGN work to tease out luminance contrast at different spatial scales (see figure below for a notional example). The result is effectively an edge or border map of a scene.

Collections of neurons in the LGN perceive local luminosity contrast. Taken together they provide a full edge map of an image.

Other layers in the LGN play a similar role, but instead of focusing on luminosity, they map out regions of color contrast.

Other collections of neurons in the LGN perceive local color contrast. Taken together, they provide a map of color contrast variations. Some neurons are tuned specifically to identify areas of red/green contrast, others highlight areas of yellow/blue contrast.

Interestingly, the majority of the vision-related connections coming into the LGN do not come from the retina. Instead, something like 95% come from other processing centers further along the visual pathway. This suggests that there are significant excitatory and inhibitory feedbacks that help guide our attention to and processing of even these low-level image features.

Visual Cortex

The next stop for signals from the retina is the visual cortex, which actually sits all the way at the back of the brain. Like the LGN, the visual cortex is also organized into a series of six layers, V1-V6. These layers encode information about the orientation of edges (V1), the spatial frequencies of textural regions (V2, V4), and the presence of color differences (V2, V4). They can even detect simple shapes and illusory contours (V2, V4) and aid in distinguishing between figure and ground (V2). They identify coherent motion in parts of the visual field (V3), note the speed and direction of this motion (V5), and respond to the presence and orientation of long visual contours, i.e. leading lines (V6).

It’s been posited that even at this very low level, our brains have preferences for certain visual features and their arrangements. This is the result of the evolutionary advantage(s) that those elements may help yield. These include preferences, say, for images where the subject is well isolated, as well as for regions of higher contrast within an image (see, for example, this earlier Fstoppers article). These image features allow our brains to more efficiently apportion our limited energy and attention. The result, through a connection back to the amygdala, is a subconscious emotional reaction to these features, even just as an abstract collection of visual stimuli with no symbolic meaning.

Inferior Temporal Cortex

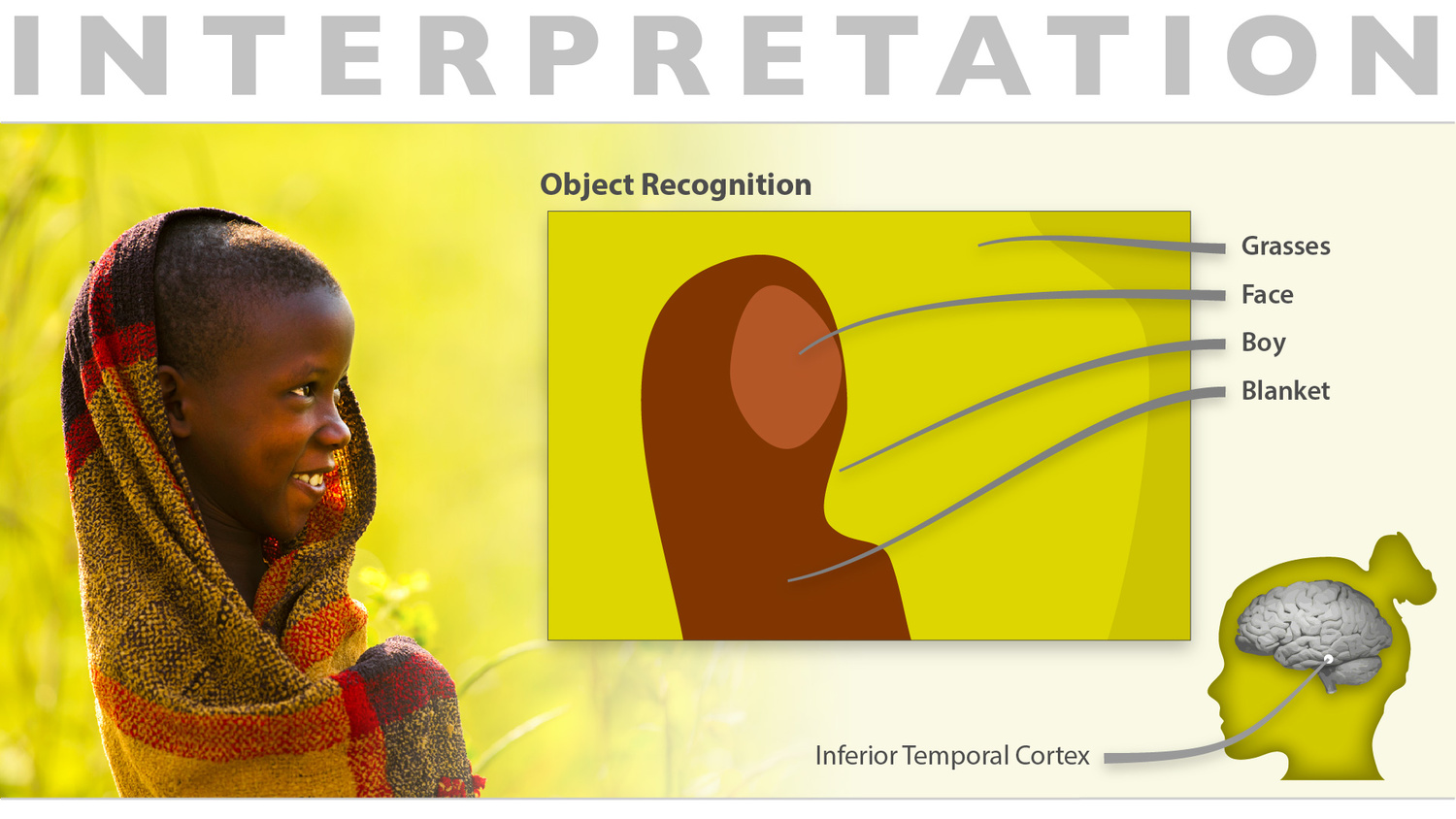

Results from the visual cortex feed into the inferior temporal cortex (IT). It's here that the arrangement of edges, shapes, and colors perceived in the visual cortex is compared to previously stored memories of objects and tagged with an identity. The low-level elements of an image are given meaning, coalescing to form, say, an elephant or a smiling boy. They become recognizable as the subject(s) of our image. Connections back to the amygdala further allow us to directly attach emotional reactions to these subjects based on our past experiences. The reverse is also true. Emotional responses generated in the amygdala are fed back to areas such as the visual cortex, where they can affect our attention to and processing of subsequent visual information.

The inferior temporal cortex generalizes the primary elements of a scene and assigns identities to them based on our previous experiences.

The inferior temporal cortex generalizes the primary elements of a scene and assigns identities to them based on our previous experiences.

There’s even a region of the inferior temporal cortex called the fusiform face area (FFA) that is specifically charged with recognizing faces. Research has suggested that individual neurons within the FFA may respond to a single, specific person’s face. They’ve been colloquially dubbed Jennifer Aniston cells for the celebrity whose images were used in the study. Given that the recognition of faces has been so important to our evolutionary survival that we developed a region in the brain which specifically performs just this task, it may not be surprising that portrait photography can elicit such strong emotional responses.

Other Areas of the Cerebral Cortex

The inferior temporal cortex marks the end of vision-specific processing in the brain, but that doesn’t mean that’s the end of the story. In addition to connecting to the amygdala (critical to our emotional memory and targeting our attention), the IT also connects to the hippocampus (a key area of the brain for learning) and the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is kind of the seat of conscious thought. It’s what gives us our personality, it’s where high-level decision-making is performed, it’s key to our understanding of language and speech. Studies have shown a direct correlation between the observation of art and activation of portions of the prefrontal cortex.

The prefrontal cortex itself has numerous connections with other regions of the brain, allowing it to integrate visual information with sensory information of other types. It’s here that the objects identified in the IT can be assembled together and analyzed with conscious thought. It’s here that we may begin to “see” an image in a broader context, understand something about the story behind it. It’s through the telling of stories, the invocation of higher levels of empathy and understanding, that we can have the most profound effect on viewers. In fact, research has shown that when we experience a well-told story, nearly all of the parts of our brain light up that would light up if we were actually having the experience ourselves. A good story can tap into our hopes and fears, our empathy or anger. It can yield a physical response, making our brow furrow or the corners of our mouth nudge upwards into a gentle smile.

I went to see the movie “Free Solo” earlier this year with my family. I think we all spent half the movie wiping our palms on our pants. We were physically sweating from watching a story unfold before us. This is facilitated in part by a connection between the cingulate cortex (where many emotions are processed) and the hypothalamus, which helps control things like your body temperature. That’s a physiological response to art, which in my book is pretty amazing.

Breaking Down an Image

The myriad connections between the visual system, many portions of the limbic system, and the prefrontal cortex allow us to form emotional responses to artworks on many different levels. These connections provide the visual arts with their power. But how does this neurological view of things relate to the aspects of image observation and critique that we’re used to dealing with: framing, composition, subject novelty, etc.?

Let’s think for a moment about the functional objectives of the main visual processing centers. Recall that the visual cortex examines things like the location of edges, color differences, and simple shapes. These are things we typically think of as being part of an image’s abstract composition. The inferior temporal cortex assigns an identity to these abstract collections of edges and forms. They become symbolic representations of an image’s subjects. Finally, the prefrontal cortex facilitates a deeper, conscious introspection of the meaning of these subjects, what might have led to their juxtaposition in the current photograph, what might happen to them in the future. The involvement of the prefrontal cortex allows us to process an image’s story.

The visual processing regions within the brain are wired to extract information from an image at increasing levels of complexity and abstraction. Artistically, these correspond, roughly, to information about an image’s composition, its subject matter, and the story it may seek to tell.

The visual processing regions within the brain are wired to extract information from an image at increasing levels of complexity and abstraction. Artistically, these correspond, roughly, to information about an image’s composition, its subject matter, and the story it may seek to tell.

This, then, gives us a context within which to think about how the more familiar, artistic aspects of a photograph might come into play and how they may fit together. The figure below enumerates many of these artistic elements while attempting to capture their relationship to the higher-level organizational structure of an image and, in turn, to the corresponding visual processing regions within the brain. A detailed discussion of each of the elements is beyond the scope of this post, as each likely deserves an entire article in its own right (and some have already gotten them). What I’d like to call attention to here is the broader perspective: that there is likely an organizational structure to the many different artistic aspects of a work of art — and a biological motivation for that structure. In the third article in this series, we'll spend a little more time thinking about these specific ingredients of an image and their relationship to the process of image creation.

The artistic elements of an image fall into roughly three categories, contributing to an image’s composition, subject, or story. These are, in turn, processed within different regions of the brain.

The artistic elements of an image fall into roughly three categories, contributing to an image’s composition, subject, or story. These are, in turn, processed within different regions of the brain.

There are, however, a few high-level things to note about the different categories of artistic elements.

Compositional Elements

As we've seen, the things we think about as being elements of composition likely have their roots in processing that occurs within the visual cortex. An understanding of and emotional response to an aesthetically pleasing composition doesn’t require knowledge about what that arrangement of edges and forms represents (a decision only made later on in the inferior temporal cortex). These low-level contributions to an image’s composition include things like color theory, contrast, the rule of thirds, visual mass, leading lines, diagonals, symmetry, etc. Evolutionary benefits to the perception of each — along with the corresponding connections that have developed between the visual cortex and limbic system — can yield a strong emotional response to a photograph without regard to, or even in the complete absence of, its symbolic meaning.

One interesting exception may be sight lines. Artistically, these can play as significant a role in directing a viewer’s attention within an image as leading lines. Yet, while leading lines are likely processed within the sixth region of the visual cortex, sight lines can’t be processed until we know what an object is. We need to know that it has eyes. We need to understand that its gaze is directed toward a particular region of the image. That suggests a much higher level of cognitive processing, one that almost certainly involves encoding done in the inferior temporal cortex.

Subject Matter

Our brain’s desire to limit our attention and processing to only those aspects of a scene of greatest relevance to us drives a predilection towards, for example, regions of higher contrast. This same emphasis extends to subject matter as well. We can’t conceivably process every bit of the gigabytes upon gigabytes of visual information put before us every day. Our very limited processing power must be expended only on those things most relevant to our survival or enjoyment. We pay attention to the location and trajectory of cars coming toward us on the road, for example, but not to what their grills look like, what the license plate numbers are, or to the veins in blades of grass slipping by on the side of the road. One bit of information is necessary for our survival; the other bits are largely irrelevant. It’s for this reason that it’s so hard to create an image that’s actually interesting. Our brains automatically filter out 99.9% of everything we see. To stand out, the subject matter must often be so unusual, unexpected, or aesthetically appealing as to demand a slice or our limited attention.

I suspect, for example, that this is the reason that split toning has gained such favor in recent years. It lends an air of the unexpected to what might otherwise be a relatively mundane subject. There’s something unusual going on that our brains can’t quite make sense of. We have an expectation about what the colors of different objects should be, how light and shadow should relate to one another. That slight mismatch draws a bit more of our attention to these photos.

While a flock of birds may be a common sight, an uncommon perspective on them can make for a more interesting image.

This also helps to explain the appeal of travel photography. To someone who grows up in central Africa or southern India, the sights, smells, and sounds of those regions will be quotidian and mundane. To a photographer from the west, they may be mesmerizing for their unexpectedness.

Story

Verbal storytelling existed long before painting and certainly before photography came into fashion. The ability of both to tell a good story and extract complex, abstract, nuanced meaning from one is both ancient and necessary to our survival as social creatures. In prehistoric times, oral stories would have allowed us to retain knowledge about hunting techniques or dangers, bolster tribal allegiances, or bring to life the abstract moral principles critical to surviving within a small community. Our response, intellectually and emotionally, to a good story is just as strong today as it was then. A good story can still make the hair stand up on the back of the neck, the heart swoon, or the brow furrow. It can tap into our underlying fears, our unspoken dreams. The more time I spend photographing, the more time I spend soaking up the amazing work of other photographers, the more convinced I become that it’s here that the greatest potential power of an image lies.

An image can juxtapose subjects — a man, a bench, a few cartoons meant for children — in a way that might engage your conscious brain to ponder deeper questions, to wonder what might have come before, or imagine what might follow.

In this article, we’ve looked at the process of visual communication from the perspective of the viewer. In the next article, we’ll flip things around and look at this process from the perspective of the photographer. In a third article, then, we’ll examine the ways in which the two perspectives relate to and intersect with one another. We'll think about how we can use our understanding of image interpretation to guide the process of image creation.

You’re killing it with the low level conceptual photography discussions.

Really looking forward to the next entries of this series.

Hey Chase, awesome! Glad they're of interest...

New fan here. This kind of article is right in my world of thinking... both in writing and photography.

Loved the Tolstoy quote. I emphatically agree.

That's awesome Cathleen.Yea, I really like the Tolstoy quote as well. Couldn't have said it better myself, but then not a surprise when you're talking about ... Tolstoy!

Honest admission... I skimmed fair chunks of "War And Peace." I'm a former soldier and the troop movement stuff even bored me. Haha!

But Tolstoy's skill in building an image with words... sticks with me. Somehow, all these experiences inform what I choose to shoot or write.

I really appreciate the affirmation of the science of the mind. :)

Awesome article, looking forward to the next part

Hey Brent, your articles are extremely well researched and go deeper than I've seen anywhere else. (And you're faster thinking, researching and writing than I'm learning Python to come with apps for your ideas :-D.) Put this all together and it would make for a unique photography analysis book. BTW. I'm just reading up on links and common ideas between photography and music so that may be another avenue for you to explore. Cheers!

Hey Jiri, that's an awesome idea! One of our superb editors is a music theorist. Maybe we can see if we can tag team one...

I love a proper article, not a copy paste 10 min video with 40s of content.

Thanks for this, a good read!

Thanks Rob, glad you enjoyed!

God***n Brent, what a well researched and assembled article. I always wanted to get a little more into the "science" of art and perception, but felt a little too lazy to research. You summarized it perfectly. And obviously, I feel flattered for being linked in such an informative article! Looking forward to the next parts...

Cheers

"... too lazy to research." LOL! That's a bummer. You could've saved me a lot of work...

Excellent article, Brent! I really appreciate a well thought out and researched piece. I look forward to the next parts!

Yet another great article Brent, can't wait til you post another one! :)