Focus and recompose is an extremely common method for getting around AF sensors with limited AF point spread, but it's an imperfect technique that could be causing you more issues than it's worth.

The Problem

A common complaint (particularly with DSLRs as opposed to mirrorless cameras) is that poor AF spread point across the frame makes it difficult to create off-center compositions. This frequently becomes an issue in portraits, where images that do not place the subject dead center are often desired. It's particularly compounded by the fact that portrait photographers often use medium-length telephoto lenses at short subject distances with wide apertures, meaning very narrow depth of field. Here's why that's a problem.

The Math

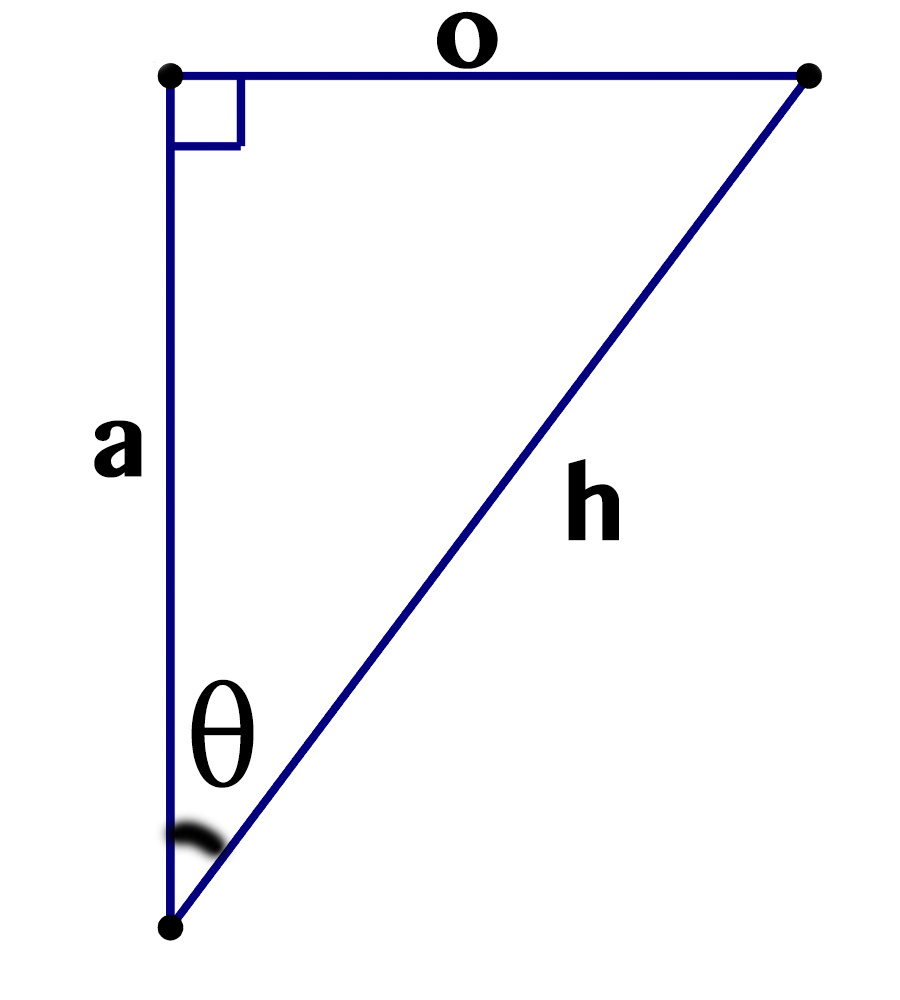

Remember trigonometry? SOH-CAH-TOA? It's back. Sorry, but we're about to get triggy with it. Let's say I have a right triangle, and I label the bottom angle theta.

Then, I have three sides, the hypotenuse, the side opposite theta, and the side adjacent to theta. Having fun yet? Me too. The trig function I'm interested in is cosine, which tells us the ratio of the length of the adjacent side to the hypoteneuse for a given angle θ. Why am I interested in that? Let me show you.

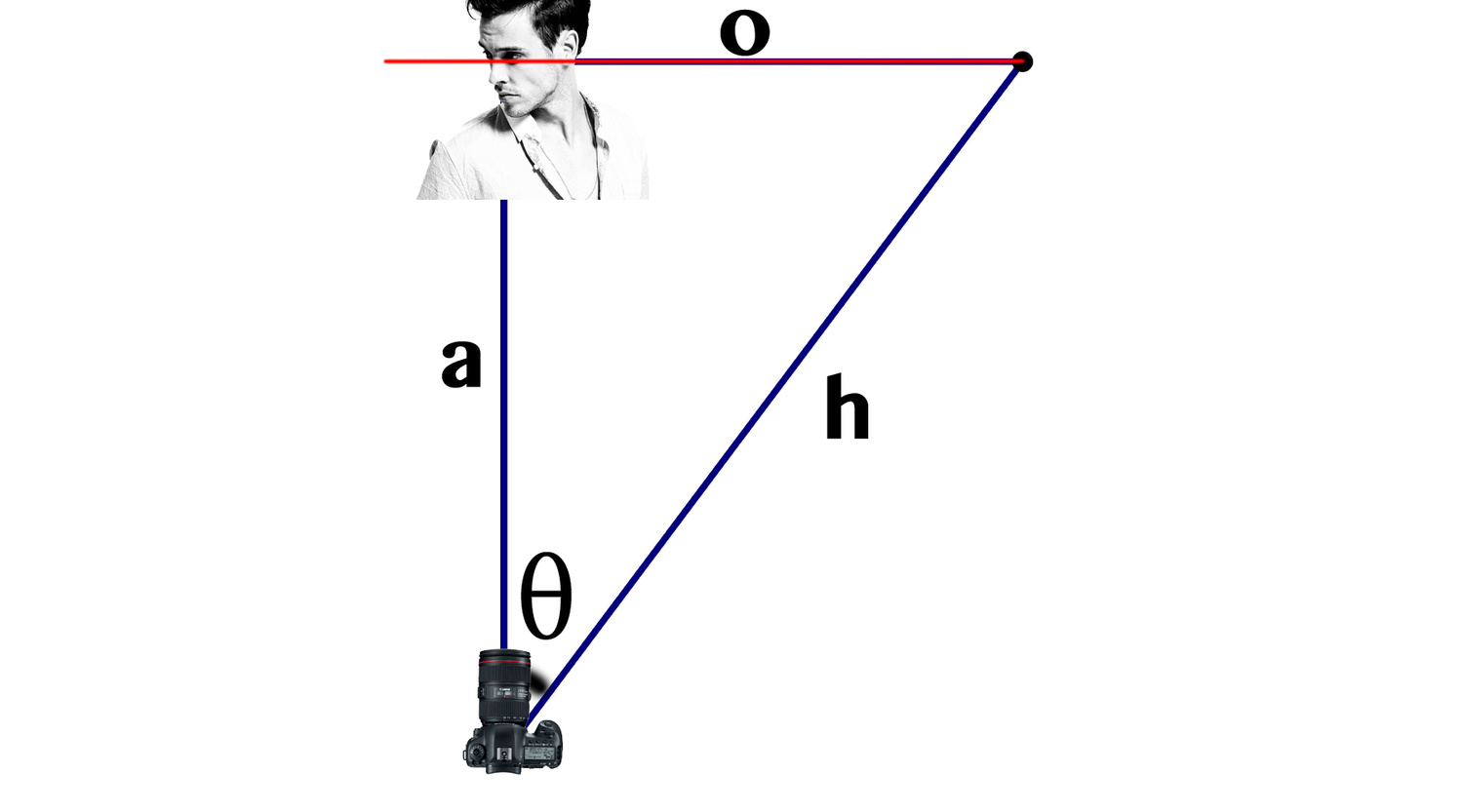

Meet Ryan. He recently turned 30, loves his work as a writer and teacher, and though he wishes he weren't still single, he's holding out hope and has managed to avoid the existential crises that normally hit when changing decades. As part of his thirty, flirty, and thriving phase, Ryan is having his portrait taken for his new dating profile. To really make Ryan pop, his photographer is shooting him on an 85mm lens at f/1.8 from 5 feet away (this makes side "a" 5 feet long). This gives us a depth of field of 0.11 feet, or about 1.3 inches. Now, let's say Ryan's photographer uses the focus and recompose method, rotating the camera to the left after using the center point to get focus. Here's the key thing to note: the side o represents the plane of focus. Notice how it directly intersects his eyes.

The plane of focus is in red.

The angle has been exaggerated for the purposes of illustration.

Notice that the plane of focus is now behind Ryan. That's the curse of having flat image sensors. But just how much has it shifted? Well, that's just the difference between the length of side h of the triangle and side a. Here's the math:

In other words, the focus point where Ryan is located has shifted 5.077-5= .077 feet or 0.92 inches behind him. Not a big deal, right? It wouldn't be, except the near DOF limit is this case is 0.63 inches in front of him, meaning the entire window of acceptable focus has shifted behind him, and his eyes are no longer within the DOF limits. Whoops.

The Solution(s)

There are a number of ways around this, each with benefits and drawbacks.

1. Tell Camera Manufacturers to Spread Their AF Points Across the Frame

Benefit: This problem wouldn't exist.

Drawback: They're likely not going to listen to us.

2. Shoot With a Normal Focus Point, Then Crop In

Benefit: Your plane of focus will not shift.

Drawback: You'll lose resolution. If you're shooting on a high-resolution camera such as the Nikon D810 or Canon 5DS, you probably won't care. Even on my 30-megapixel 5D Mark IV, it really doesn't bother me.

3. Get Clever With AFMA

Since your focal plane is shifting in a predictable manner, you can take advantage of your camera's AFMA adjustment to dial in a bit of front compensation, pulling the focal plane back toward the subject. However, I don't recommend this for the reasons below.

Benefit: It will alleviate the issue.

Drawback: This method should only be used if you constantly compose portraits the same way and focus and recompose at about the same angle. Otherwise, if you try to take a center-composed shot, for example, it will be front-focused. So, unless you make your living by taking the exact same portraits via the exact same method all the time, skip this.

4. Take More Centered Portraits

Benefit: You'll be using the AF points of your camera as intended and can expect a higher keeper rate.

Drawback: It limits you compositionally.

I like centered portraits. Call me crazy.

5. Stop Down

Benefit: By increasing the depth of field, you can keep the shift within acceptable limits.

Drawback: If you're someone who likes melty wide-aperture portraits, this kills that. Also, you're not solving the problem; you're just reducing its severity.

6. Shoot in Live View

Benefit: You'll get a wide focus range across the frame.

Drawback: It can be difficult to shoot in live view, battery life suffers, contrast-detect AF is typically slower, and it may be tricky to precisely select focus on a smaller feature such as the eyes.

7. Lean Back

So, since we're talking about corrective distances on the order of a few inches, you could conceivably focus and recompose, then lean back ever so slightly to pull the plane of focus back where it belongs.

Benefit: It allows you to compose as you please, but still keeps the image sharp.

Drawback: You're estimating distances. If you typically shoot with the same lens at about the same distance, you can probably develop decent instinct and muscle memory for how much to lean back. I've tried this, and while it's not perfect, I do notice an increase in my keeper rate.

8. Compromise

Shoot with the AF point nearest your subject in the desired composition, then focus and recompose.

Benefit: You get your desired composition and reduce the error.

Drawback: You don't completely eliminate the error, and depending on the spread of AF points on your particular camera, the correction may not be significant.

Conclusion

Focusing and recomposing is an imperfect solution to a peculiar problem. It's important to be aware of the consequences of it, however, particularly if you often notice your portraits being slightly out of focus. I typically use the solution of leaning back or simply cropping in; both work sufficiently well for my shooting. Use whatever works best for your purposes and style.

Thank you for the article!

..and what about creating the composition and use one of the 61 AF points choosing one of them on the left or right without moving or leaning back?

just curiosity, i'm probably missing something but last week taking some portraits it seems to have worked.

Thank you!

You'll still get the same error, but it'll be smaller!

For what it's worth, I noticed a lady photographer recently taking full length portrait at a wedding, first focussing downwards on the bride's dress someplace, then recomposed approximately the same distance to get the background in frame ..... interesting.