Camera specifications have become reasonably standardized over the years, but lens specifications are a different animal entirely. Optical performance resists easy quantification, and manufacturers have learned to fill that void with impressive-sounding terminology that obscures more than it reveals. This guide cuts through the jargon to explain what each specification actually measures, when it genuinely affects image quality, and how to read between the lines when comparing options.

Maximum Aperture: The Number Everyone Overvalues

The maximum aperture rating remains the first spec most photographers check, and for good reason: it determines both light-gathering capability and depth of field control. But the practical differences between common aperture ratings deserve more scrutiny than they typically receive. The jump from f/1.8 to f/1.4 represents only two-thirds of a stop of light, easily compensated with a minor ISO adjustment on any modern camera. The depth of field difference exists but proves marginal in most shooting scenarios. Unless you specifically need the thinnest possible focus plane for a particular creative effect, or you're regularly shooting in extremely low light without flash, the f/1.4 premium often buys you primarily additional weight and cost rather than meaningfully different images. A Canon RF 50mm f/1.8 STM weighs 160 grams and costs a fraction of the Canon RF 50mm f/1.2L USM, which tips the scales at 950 grams. For most shooters, that weight and price difference buys marginal practical improvement.

Variable aperture zooms get a bad reputation they don't entirely deserve. Yes, an f/3.5-5.6 kit lens loses light as you zoom in, but modern high-ISO performance has largely neutralized this as a practical concern for stills. The constant f/2.8 professional zooms maintain their appeal for event shooters who need consistent exposure across focal lengths and video shooters who can't have aperture shifts mid-clip, but the constant f/4 options represent a compelling middle ground that's often overlooked. Lenses like the Sony FE 24-105mm f/4 G OSS or Nikon Z 24-120mm f/4 S deliver much of the optical quality of the f/2.8 versions at substantially reduced size and weight.

Cinema shooters encounter T-stops rather than f-stops, and the distinction matters more than most photographers realize. An f-stop describes the geometric ratio of focal length to aperture diameter, but it doesn't account for light lost to absorption and reflection within the lens elements. A T-stop measures actual light transmission. Two lenses marked f/1.4 might transmit noticeably different amounts of light depending on their optical complexity. For video work requiring matched exposure across multiple lenses, T-stop ratings provide more reliable information. For stills shooters, the difference rarely matters in practice since we meter through the lens anyway.The physics of faster apertures create unavoidable tradeoffs. Light-gathering capability scales with aperture area, not diameter, so gaining one stop of light requires increasing the entrance pupil diameter by a factor of roughly 1.4 (the square root of 2). This is why the f-stop scale progresses in those familiar 1.4x multiples. But even that modest increase in diameter cascades through the entire optical design: front elements grow larger, more complex corrections are needed to control aberrations across the wider aperture, and weight increases substantially. A 50mm f/1.2 isn't just a better version of a 50mm f/1.8; it's a fundamentally different lens with different compromises, different handling characteristics, and often different rendering personalities.

MTF Charts: Actually Useful Data Buried in Confusing Presentation

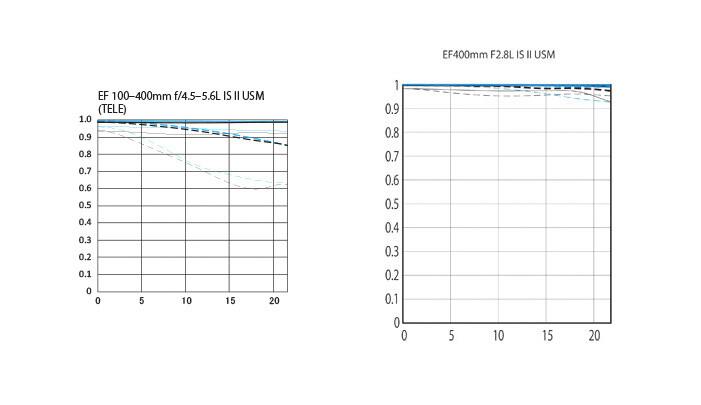

Modulation Transfer Function charts represent the closest thing to objective optical quality data that lens manufacturers publish, yet most photographers either ignore them or misinterpret them. An MTF chart measures how well a lens preserves contrast when rendering fine detail at various distances from the image center. The vertical axis shows contrast reproduction from 0 to 1, with 1 representing perfect contrast preservation. The horizontal axis shows distance from the center of the image circle to the edge.

The charts typically show multiple lines representing different measurements. The 10 lines per millimeter measurements indicate contrast reproduction, showing how well the lens maintains tonal separation between light and dark areas. The 30 or 40 lines per millimeter measurements indicate resolving power, showing how well the lens handles fine detail. Each measurement gets plotted twice: sagittal lines show performance for detail oriented radially from center to edge, while meridional lines show performance for detail oriented tangentially around the image circle. When these lines diverge significantly, you'll see astigmatism in the rendering, with certain oriented details appearing sharper than others.

Cross-brand MTF comparisons should be approached with significant skepticism. There's no universal standard for how these measurements are made. Some manufacturers publish theoretical calculated MTF based on optical designs, while others publish measured data from production samples. Testing distances, measurement equipment, and presentation formats vary. Canon and Nikon charts, for instance, don't quite mean the same thing even though they look similar. Use MTF data to compare lenses within a single manufacturer's lineup, but be cautious about drawing conclusions across brands.

What MTF charts cannot tell you includes nearly everything else that matters about a lens. Focus accuracy, autofocus speed, bokeh character, flare resistance, build quality, focus breathing, and handling characteristics exist entirely outside this measurement. A lens can post excellent MTF numbers while having distracting bokeh, unreliable autofocus, or terrible flare resistance. The charts are useful, but they're one data point among many. You can read more about them here.

Optical Elements: What All Those Fancy Glass Types Actually Do

Lens designers add elements to correct aberrations, the various ways that real optics fail to focus all wavelengths and angles of light to a single point. Each type of specialized element addresses specific optical problems, though marketing materials rarely explain what those problems are.

Extra-low dispersion glass (called ED, UD, SLD, or various other proprietary names) primarily controls chromatic aberration, the failure of different wavelengths of light to focus at the same point. This creates color fringing, most visible as purple or green edges on high-contrast boundaries. The relationship between focal length and chromatic aberration is more complex than simple "longer equals worse," since different types of CA (longitudinal versus lateral) depend on aperture, magnification, and optical design rather than focal length alone. That said, long telephoto designs historically struggled with CA correction using conventional glass, which explains why ED elements became standard in that category first. Wide-angle and normal lenses can often achieve acceptable correction with simpler formulas.

Aspherical elements address spherical aberration, which causes light rays passing through the edges of a lens element to focus differently than rays passing through the center. Traditional spherical lens surfaces produce this effect inherently; aspherical surfaces curve differently at different distances from the center to bring all rays to a common focus. Aspherical elements also allow designers to achieve certain corrections with fewer total elements, reducing complexity, weight, and potential for flare. The tradeoff involves manufacturing difficulty. Molded aspherical elements are relatively affordable but can show concentric rings in out-of-focus highlights. Ground and polished aspherical elements avoid this but cost substantially more to produce.

Fluorite elements appear in high-end telephotos primarily for their anomalous partial dispersion characteristics, which allow optical designers to correct chromatic aberration in ways that conventional glass cannot achieve. The material's refractive index behavior makes it uniquely effective at eliminating the color fringing that plagues long focal lengths. You'll find fluorite in lenses like the Canon RF 100-500mm f/4.5-7.1L IS USM and similar professional telephotos. That fluorite is also less dense than optical glass provides a secondary benefit for weight-conscious telephoto designs, but manufacturers wouldn't tolerate its expense, fragility, and temperature sensitivity if the optical properties weren't the main draw.More elements isn't inherently better. Each air-to-glass surface introduces opportunities for light loss and internal reflections. Complex zoom lenses might contain 20 or more elements; simpler primes might use 7 or 8. The additional elements in zooms are there to maintain acceptable performance across the focal range, not because more glass produces better images. Some of the most celebrated lenses in history used relatively simple optical formulas.

Every manufacturer invents proprietary names for similar technologies, making direct comparisons unnecessarily difficult. Canon's UD glass, Nikon's ED glass, Sigma's SLD glass, and Tamron's LD glass all address the same fundamental problem. The marketing names function primarily as brand differentiation rather than meaningful technical distinction.

Coatings, Motors, and Stabilization: The Supporting Cast

Lens coatings reduce reflections at air-to-glass surfaces, improving both light transmission and resistance to flare and ghosting. A single uncoated air-to-glass surface reflects roughly 4% of incident light; multiply that across 30 or more surfaces in a complex zoom and the losses become significant. Modern multi-coating reduces these reflections to fractions of a percent per surface.

The progression from single coating to multi-coating to nano-structure coatings shows diminishing returns but real differences in challenging conditions. Shooting directly into bright light sources reveals coating quality faster than any specification. A well-coated lens maintains contrast and color saturation when pointed toward the sun; a poorly coated lens washes out and produces distracting ghosting. This matters more for zooms than primes simply because zooms have more surfaces to coat.

Autofocus motor technology affects shooting experience more than image quality, but the differences are substantial. The cheapest DC micro-motors are slow and noisy. Stepper motors offer quiet, smooth operation well-suited to video. Ring-type ultrasonic motors (USM, HSM, SWM, and similar) provide fast acquisition with instant manual override. Linear motors represent the current high-end, offering extremely fast and precise movement particularly suited to tracking applications and video.

Motor power must match the optical design's focus group mass. Some optically excellent fast primes focus surprisingly slowly because their large, heavy focus elements require substantial force to move quickly. The camera body's autofocus system matters as much as the lens motor; the best lens motor cannot compensate for a weak phase-detect system or slow processing in the body.

Optical image stabilization ratings seem straightforward but prove slippery in practice. A "5-stop" rating means the lens should allow sharp handheld shots at shutter speeds 5 stops slower than conventional wisdom suggests. If unstabilized technique requires 1/200 second for a 200mm lens, 5 stops of stabilization should theoretically allow 1/6 second. Reality rarely matches these laboratory numbers. CIPA testing standards use controlled conditions that don't account for subject movement, user fatigue, or the variable micro-tremors of actual human hands. Lens stabilization still offers meaningful advantages for long telephotos where body-based stabilization struggles with the leverage of extending long optical tubes, but the specific stop ratings deserve healthy skepticism.

The Specs That Don't Appear on Spec Sheets

Bokeh quality resists specification because it's inherently subjective and emerges from complex interactions between multiple design elements. Aperture blade count affects the shape of out-of-focus highlights when stopped down; more blades approach a circle. Blade curvature determines whether that shape remains rounded at intermediate apertures or becomes polygonal. The optical formula's handling of spherical aberration influences whether out-of-focus areas appear smooth or busy.

Aspherical elements create a particular tradeoff here. They allow sharper wide-open performance and better corner correction, but they can introduce concentric "onion ring" patterns in bokeh highlights that many photographers find distracting. Some of the most clinically sharp modern lenses produce sterile, nervous out-of-focus areas because their aggressive aberration correction eliminates the gentle transitions that create appealing background rendering.

Focus breathing, the change in effective focal length as focus distance changes, barely matters for stills work but becomes immediately obvious in video when focus pulls create visible zoom effects. Lenses marketed as "breathing compensated" achieve this through various means depending on the design: internal focus group choreography, optical formulas that inherently minimize magnification change, or in some modern mirrorless systems, in-camera digital correction that crops and scales to maintain consistent framing. Focus shift, a separate phenomenon where the focus plane moves as you stop down, primarily affects portrait photographers who focus wide open but shoot at smaller apertures.Weather sealing lacks any industry standard definition. One manufacturer's "weather sealed" lens might have comprehensive gaskets at mount, switches, rings, and front element; another's might have a single O-ring at the mount. The fluorine coatings on front elements that some manufacturers advertise help with cleaning but don't prevent water intrusion. If environmental protection matters for your work, research the specific sealing implementation rather than trusting the marketing claim.

Buying Guidance Without the Nonsense

Different applications demand different compromises, and understanding which specifications actually matter for your work prevents overspending on capabilities you'll never use while ensuring you don't underinvest in the characteristics that will affect your images.

Portrait work benefits from pleasing wide-open rendering, smooth bokeh, and accurate eye-detect autofocus. Edge sharpness matters little when your subject occupies the center of the frame and the background dissolves into blur. If you want to develop your portrait skills further, Fstoppers offers Perfecting the Headshot for mastering that genre. Landscape work inverts these priorities: corner sharpness stopped down, flare resistance when including the sun in compositions, and filter thread compatibility for graduated filters take precedence over maximum aperture. For landscape shooters looking to improve their craft, Photographing the World: Landscape Photography and Post-Processing covers both shooting technique and editing workflows. Event and wedding photography demands autofocus speed and reliability above almost everything else; a slightly less sharp lens that nails focus consistently will outperform a sharper lens that hunts or misses in challenging light. Video work adds requirements for quiet focus motors, minimal breathing, smooth stabilization, and usable manual focus feel with appropriate damping and throw.

The marketing language around lenses rewards skepticism. "Professional" without context means nothing; some of the best professional work in history was made with amateur equipment. Element counts say little about optical quality; a well-designed 7-element lens can outperform a poorly designed 15-element lens. Proprietary coating names obscure rather than illuminate. Sharpness claims without MTF data or standardized testing should be ignored. Weather sealing claims without specific gasket information should prompt further research.

The best lens is the one whose compromises align with your actual shooting needs, not the one with the most impressive specification sheet. Understanding what each specification actually means, what it controls, and what it fails to measure puts you in position to make informed decisions rather than falling for marketing language designed to impress rather than inform.

No comments yet